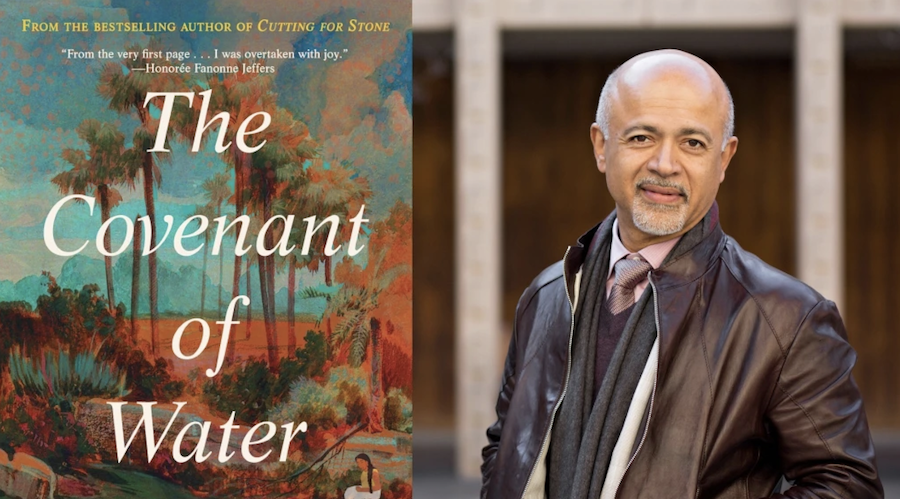

Abraham Verghese on Marrying Medicine With Literature

The Covenant of Water, Abraham Verghese’s second novel, is a masterpiece of empathetic storytelling—a spectacular saga tracing three generations of a South Indian family suffering from a rare medical condition over seven decades, beginning in 1900. The narrative is laced with tragedies and love stories, missteps and unexpected connections. A steady stream of emotional highs and lows flows amongst a wide range of characters.

During our email exchange, it was announced as an Oprah’s book club selection. Added to four starred prepublication reviews, and multiple raves upon publication this month, it’s clear the newest Verghese novel is set to be a hit. Verghese tells me he wrote The Covenant of Water before and during the pandemic, while continuing his work caring for patients and teaching at Stanford Hospital and medical school.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the past several years of pandemic, uncertainty and turmoil affected your life and work as an infectious disease specialist, a physician at Stanford Hospital, as a professor at Stanford University School of Medicine, and as a novelist working on this massive second novel?

Abraham Verghese: Covid had echoes of the epidemic that made a writer of me: AIDS. My first book My Own Country was in response to that. I took care of patients with Covid while in the role of attending physician on the Stanford wards; it was inspiring for me to see my colleagues in critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesia (who were at high risk and truly on the front lines) stepping bravely forward, and to see a new generation of infectious disease physicians being shaped by this new pandemic.

I was working on The Covenant of Water, before and during the pandemic. The novel is set in 1900s through 1970; it was affirming and poignant for me to be reminded that when people are very ill, whether in the 1919 or 2020, they turned for succor to the same things: family, faith, friends, and rituals of comfort and sustenance. Without a doubt the pandemic helped shape and affirm so much in the novel.

JC: The Covenant of Water begins in Travancore, South India, in 1900, with the marriage of Ammachi, a twelve-year-old whose mother tells her, “The saddest day of a girl’s life is the day of her wedding.” This sets the stage for a complicated story. Why begin here?

I have a small treasure trove of rare diseases that fascinate me.AV: With a book this length you won’t be surprised to learn that I experimented with several different ways of starting. In the end, the little girl who becomes such a central character, a strong mother and grandmother—a true loving matriarch—just had to begin the book. I liked the idea of playing against the grain and surprising the reader who might view her marriage as not boding well for the new bride. Too many portrayals of mothers in modern fiction can be eccentric, deeply flawed, or even evil.

Big Ammachi is a woman of quiet faith and great strength. Her marriage becomes something beautiful, even enviable. I was also being true to the historical facts: such betrothals of young girls and boys were common in my grandmother’s and great-grandmother’s era. The young bride simply became one of the children in the joint household, largely unaware of the irritating boy who also lived there who was supposedly their husband. Only when they came of age were they really allowed to be man and wife. So, it isn’t as sinister as it sounds at first blush.

JC: You follow the history of Ammachi’s family, which has roots in a small Christian community founded when St. Thomas arrived on what was known as the “spice coast’ in 52 AD, through 1977, while simultaneously tracing the evolution of present-day Kerala. To what extent is this novel, and its family origins, autobiographical?

AV: It is autobiographical inasmuch as once I decided to set the novel in Kerala, I was leaning heavily on my memories of spending summers with my grandparents in Kerala and even more time with them when I was in medical school. I was born in Africa, but my mother and father are from Kerala. The granularity of rituals and customs came from my own observations, and from research, and from talking to my mother who was approaching ninety when I began the novel, and she died before I finished.

She had once handwritten a document for my niece—her granddaughter—in response to the question, “Ammachi, what was your life like as a little girl?” That manuscript reminded me of how rich a setting the Kerala of her lifetime would be for a novel. But the Parambil family and the events that befall them are quite fictional.

JC: The Parambil family suffer from a secret curse or disorder they call “The Condition.” It dooms at least one member of each generation to death by water, even drowning in a shallow puddle. Because of this, most family members avoid water, taking inland routes instead of quicker coastal routes, for instance. What is the origin of this element of the narrative? Is this a family secret you know about personally? Did you intend to follow this thread to its surprising conclusion from the beginning?

AV: I don’t want to give too much away to the reader who is yet to engage with the book but there are several conditions that are passed on genetically that put affected families at risk for drowning when in water. And with so much water around, accidental drownings happen. However, as a longtime teacher of medicine to residents on the wards, I have a small treasure trove of rare diseases that fascinate me and that I pose to them as riddles for them to research and sort out.

I drew on one such disorder for “The Condition.” Given the abundance of water in Kerala, with its forty-four rivers, innumerable lagoons, backwaters, and lakes, the idea of water as a controlling metaphor for the story was inescapable. Not to swim in Kerala is like being unable to walk. And yes, once I gave the family this “secret,” which is a big cross for the affected individual to bear, I was committed; the conceit that runs through the book is the unraveling of this mystery.

JC: In addition to a cast of human characters that includes generations of the Parambil family and their associates, and medical professionals, a central character, Damodaran or Damo, greets Ammachi on her first night as a bride. Is the presence of an elephant common in this era in this part of India?

AV: The sighting of working elephants in south India was common, yes, and there are many temple elephants now who are central to Hindu religious festivals. Moreover, in the great forests and reserves that are all over Kerala (Wayanad in the book is just one of many), wild elephants abound. At my grandparents’ place once a week or so we might see a working elephant being led slowly past the house on the way to be bathed in the river, or from one logging job to another. It was enormously exciting to every child around. It would have been unusual for a household to own an elephant because it’s expensive, but it wasn’t unknown for the wealthy.

My elephant Damodaran is on the unusual side, very human in character, but most mahouts would find that unsurprising. If one gets close enough to look into the eye of an elephant, it’s shocking to be met by a very human gaze. That was my starting point for Damodaran, an elephant who feels like a family member.

JC: How were you able to capture the details about the flora and fauna of this region of India in such minute detail? Family stories? Your own time in India?

AV: All the above. I have vivid recollections of certain of the flora and fauna, especially sweeping overgrowth of touch-me-nots flinching in the breeze and of the banana and plantain trees my grandmother would tend behind her kitchen. I made special visits to estates and consulted planters and I paid a lot more attention to the granular details of landscape. And libraries and online images and databases were a great help.

JC: The shift from colonialism to independence, the renaming of Travancore as Kerala, and the rise of Kerala’s Naxalite movement are also elements of The Covenant of Water. How did these political elements affect the plotting of the novel?

AV: It’s impossible to ignore the political elements once you place characters in a setting where the politics affect their livelihood, causing starvation, or with the caste system, barring them from even appearing in some places. I steered away from long digressions about history as far as possible but rather tried to show my characters buffeted by events that at the time were simply their reality and only in retrospect became history as we know it.

JC: Glasgow-born Digby is raised by a single working-class mother, and knows from his mentors that he has little chance of becoming a surgeon despite his talents because of his caste, so he studies at Madras Medical College. You studied there, as well. I’m wondering if this novel is an opportunity to further reflect the value of empathetic and humane medical training and care you’ve emphasized in your medical career?

AV: I didn’t shape any of the physician characters with that agenda of advancing humanistic qualities; however, humanism in medicine is something I write about, teach, and believe in, so undoubtedly it crept into their actions. In the academic medical world, I’m known for my concerns about the waning of our bedside exam skills in “reading the body” and registering the obvious clues and the diagnoses that are self-evident rather than ordering tests will-nilly.

I also feel that medicine isn’t something outside of our experiences.In short, my pet peeves and passions in medicine make their way into the book but I wasn’t proselytizing. I also feel that medicine isn’t something outside of our experiences. Medicine is really life++ and some of our most important and transitional and life-threatening moments, and even our ultimate demise might occur in a medical situation. I’ve had the privilege and the misfortune to observe this closely over a long career. Inevitably some of that makes its way into the world I create.

JC: Some of the most vivid scenes in the novel involve patients with leprosy and the doctors who treat them. Digby spends twenty-five years at Saint Bridget’s leprosarium. What sort of research was involved in creating these characters and their experiences?

AV: Leprosy was always something I was intensely aware of as a child—all children were in both Africa (where I was born) and India (where I completed medicine) because it was a commonplace sight on the streets. One saw people afflicted with leprosy who were beggars because of it. In medical school we were exposed to patients both in the hospital and the dedicated leprosarium. And of course, leprosy is such a powerful metaphor that is still in use, speaking of someone being shunned like a leper, for example.

From time to time in Texas I would see a rare patient with leprosy from either Central and South America or else from South Asia with a pale skin lesion, lighter than the surrounding skin, and the tip-off was the fact that the skin was anesthetic—they felt pinpricks less than on surrounding skin. A biopsy would prove it. Thankfully, leprosy is no longer a common sight in the tropics the way it was. The disease is fascinating—particularly for those of us infectious diseases—for the very, very long time that the leprosy bacilli take to divide, and that means treatment must be extremely prolonged since most antibiotics work on dividing organisms by impeding growth.

Also, the organism not only evades but lives within the cells, at home in that milieu. Before HIV (another disease where the culprit happily resides within the cell), leprosy was the disease we studied to learn about the immune system, particularly T-cell immunity. For all these reasons, it was a rich subtext of the novel for me. The stigma and rejection beyond the obvious disfigurement makes this such a terrible disease.

JC: Mariamma, the granddaughter of the woman whose story begins this novel, attends medical school in Madras and begins to unravel the mystery of The Condition. Was she in your planning from the novel’s beginning? If not, at what point did she enter the saga?

AV: It’s hard to say exactly when Mariamma came into the novel. Three generations were always in my initial plan, but so much originates and also changes in the writing. At some point I knew that I wanted to introduce the medical condition in an era when it was not understood and have its biological nature become clear in later generations.

JC: Are you still treating patients, teaching at the medical school, writing? Do you have another long novel in the works?

AV: Yes, I’m still clinically involved in the medical school. I attend on the wards, and I also teach medical students and residents at the bedside on weekly teaching rounds. I’m nowhere as busy as in my junior faculty days and have more administrative responsibilities than before. Stanford and the department of medicine have afforded me the great privilege of protected time, treating my writing as the equivalent of a lab scientist, for example. I feel quite blessed.

__________________________________

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese is available from Grove Atlantic.