An Exploration of Japanese Sake with Rebekah Wilson-Lye

Sake – a fermented alcohol, brewed from rice, kōji rice, water and yeast – is one of the world’s most misunderstood beverages. It’s not a distilled spirit, and to ensure it maintains its true quality, low temperature storage is essential at all times. We sit down with Rebekah Wilson-Lye, a prominent sake expert and industry innovator based in Tokyo, to talk about what sake is actually all about. As the international marketing and export manager of Japan Sake Craft Company, she shares wisdom on everything from pairing, current sake trends, and the most common mistakes when purchasing the beverage.

Tell us about your background before you moved to Japan?

I left New Zealand 20 years ago and I really just wanted to explore the world. I was 28 years old and working in the book industry. I’d been in the independent publishing world for many years and I was a freelance journalist, so my whole world revolved around books. But working in the book industry doesn’t pay, and being a writer really doesn’t pay, so I began to dread that I’d only ever be able to explore other countries and cultures through the pages of literature. I wanted to experience distant landscapes for myself, like the Golden Pavilion of Yukio Mishima’s iconic novel, so I became an ESL teacher in order to work and travel. I moved to South Korea to teach, which is a whole separate chapter in itself, as Seoul 20 years ago wasn’t the dynamic metropolis we know today. Anyway, after two years there, I jumped across the ocean to the country I’d always dreamed of visiting, Japan.

How did you fall in love with sake?

In exactly the same way I ended up falling in love with Japan — by just diving in head first and exploring it. My first job in Japan was in a very, very small town in the Izu peninsula of Shizuoka, which is near Mount Fuji. It’s a beautiful area, famous for its seafood, green tea, mikan oranges and wasabi. In fact, if you go to a sushi restaurant in Japan, the fresh wasabi they use will most likely be from Shizuoka prefecture. During my welcoming party, I was served a glass of sake. I’d tried sake in New Zealand once before, but it was brown, served boiling hot and tasted musty, like something that had been gathering dust at the back of my grandmother’s liquor cabinet for decades. However, when I brought this sake to my lips, I was captivated by the wonderful aromas of honeydew melon, crisp apple, juicy pear and fresh banana that emanated from the glass. When I drank it, it had a delicate sweetness, an exquisite richness, a crystalline quality and a precise, yet lingering finish.

One of the most important things that I’ve discovered along that way is that sake is not just a drink, sake is a culture, it’s a world that is interwoven in the rich cultural tapestry of Japanese life.

I was amazed! I couldn’t believe this sake was in any way related to the ‘sake’ I’d tried in New Zealand. After further enquiry, I discovered it was a local sake made in Shizuoka. I then looked around and realised I was the only person at the table drinking sake — I was also the only foreigner. All the Japanese staff were drinking beer, cheap whisky, or ‘Chateau Cardboard’ [boxed wine], which just didn’t appeal to me at all. As I made friends in Japan, I realised that none of them drank sake either — it had a reputation as an old person’s drink, and had little or no appeal to my Japanese friends. But sake was an absolute revelation for me, so it became my mission to learn more about it.

While I was living in the countryside, I started to learn Japanese and I memorised the names of sake I liked, as well as the prefectures where they were made, so that I could order them again in restaurants or get recommendations from the staff.

In a way, I used sake to explore Japan. Soon I was on a train travelling to another region or prefecture to discover more sake. When I went to a brewery, or brewing area, I’d inevitably meet locals who’d take me to their favourite izakaya to drink local sake. Slowly, over the years, as I was exploring the countryside of Japan, I was tasting more and more sake, learning from brewers and making my own discoveries, so my knowledge started to build up. Eventually, I would gain professional sake certification and start my own sake consultancy, which then lead to my current position at Japan Craft Sake Company, where we work to create solutions that will ensure the future growth of traditional industries such as sake brewing.

One of the most important things that I’ve discovered along that way is that sake is not just a drink, sake is a culture, it’s a world that is interwoven in the rich cultural tapestry of Japanese life. When you explore sake, you learn about Japanese culture, the character of local people, their region, their environment, and the wonderful food and crafts that are associated with it. You discover ancient wisdom that is now backed up by science – Buddhist monks brought back knowledge of fermentation and kōji making from China and developed the fundamental techniques that would become the basis of Japanese fermentation culture and the sake brewing methods that we use today. Brewers were also stabilising their sake through pasteurisation hundreds of years before Louis Pasteur had the idea. So you could say, it’s an ongoing love affair and journey of discovery!

While sake is seemingly a very simple ferment, it is actually remarkably complex.

So a very basic question – what exactly is sake?

That is a very good question. In simple terms, sake is an alcoholic beverage that is fermented from steamed rice, kōji rice, water and yeast. The key word here is fermented. Sake is not a spirit, it is not distilled, and it has a very simple ingredients list. You can’t add flavourings or sugar, you can’t even add preservatives to keep sake stable.

While sake is seemingly a very simple ferment, it is actually remarkably complex.

It is also extremely sensitive to external elements like sunlight and heat. You can pasteurise it, but there will still be some dormant microbial activity that can reactivate even after pasteurisation. So if you store sake in a warm ambient environment for an extended period of time, you can quickly destroy the quality and flavour that the brewer intended to produce. Therefore, correct storage is crucial in ensuring sake maintains its optimum condition. -5ºC is the ideal storage temperature (I store sake in my freezer at -7ºC), but storing it at around 5ºC in your home refrigerator is fine if you plan to drink it within one or two months.

I often see people overseas drinking sake in a shot glass like vodka or tequila. Please don’t do that. There are a plethora of sizes and shapes of vessels you can enjoy drinking sake from.

What is the biggest misunderstanding about sake?

The biggest misconception about sake is that all sake tastes the same. It’s something I hear a lot, but in fact there is an enormous diversity of styles and flavour profiles, it’s just that the full spectrum of what is produced in Japan doesn’t make it overseas [exports only represent around 4~6% of the sake market]. Unlike wine however, the differences on the nose and palate are not as pronounced. That’s where the misconception comes in: although there is a wide variety of aromas and flavour profiles, the differences are subtle, perhaps even enigmatic to some. So don’t expect the dramatic range of flavour that you would get when comparing a sweet Moscato d’Asti from Piedmont, to a big, tannic, oaked aged shiraz from Australia. Instead you can enjoy the subtle yet compelling variations, especially when you compare a fruity ‘premium’ sake, made with extremely polished rice and highly aromatic yeast, with a robust, umami-driven junmai, a creamy yet piquant nigori (cloudy sake) or an ambrosial koshu (aged sake).

What are other common misconceptions about sake in the west?

Well, a common one is that sake can only be paired with Japanese food. Of course, sake does have a natural affinity to Japanese cuisine, but it should not be exclusively limited to it.

Also, people think that sake is high alcohol, because they’ve confused it with shōchū, which is a distilled spirit. This is an easy mistake to make if you can’t read Japanese as they both look the same in the glass, and the bottles and labels are similar too. Actually, if you put a bottle of sake and a bottle of shōchū in front of most Japanese people, they probably won’t be able to tell the difference either. The best way to confirm if it’s sake or not is to check the ABV on the label: sake’s ABV is generally around 15~17%, similar to a strong wine, while shōchū’s is between 25%~40%. Our company has developed an app called Sakenomy to help solve this problem. You can get information about the sake you’re drinking simply by scanning a photo of the bottle in the app — it’s effectively the Vivino of sake.

Sake has around seven times more amino acids than wine, and, as we all know, amino acids are the building blocks of umami flavour. So in a way, sake acts like liquid MSG, it compliments food by amplifying the umami-ness and natural flavour of the ingredients.

There is also some confusion about how to drink sake — I often see people overseas drinking sake in a shot glass like vodka or tequila. Please don’t do that. There are a plethora of sizes and shapes of vessels you can enjoy drinking sake from; fine porcelain ware, rustic pottery, delicate usuhari glass, pewter, lacquer ware, etc… But sake is glorious in stemmed glassware too. I highly recommend the Zalto Universal glass — it’s my glass of choice for all types of sake.

Can you tell us a bit about pairing sake with food?

There’s a saying in Japan that “sake doesn’t fight with food” — after 20 years of drinking sake with almost every meal and type of cuisine, I can personally attest to this. In fact, I find that sake is much easier to pair with food than wine. Firstly, sake is free of tannins and has much less tart citric acidity than wine. This means you never experience that sharp clash you sometimes get when pairing wine and food. However, sake has around seven times more amino acids than wine, and, as we all know, amino acids are the building blocks of umami flavour. So in a way, sake acts like liquid MSG, it compliments food by amplifying the umami-ness and natural flavour of the ingredients. I’ve enjoyed sake with everything from dry-aged Galician beef, to multi-course meals at three star Michelin French restaurants, to Vietnamese, Thai, Jiangzhe, Modern Nordic and Mexican dishes, American comfort food to delicate desserts and so much more — sake’s pairing potential is borderless. Sake also has a natural affinity to fermented foods, and I particularly love pairing it with cheese. It’s a divine, morish pairing that will convince anyone that sake is a great match for non-Japanese food! I highly recommend grabbing a couple of bottles of sake and a well stocked cheese platter and discovering this for yourself.

Could you give some examples of traditional Japanese food pairings with sake?

As I mentioned before, I fell in love with sake by exploring Japan, and during my travels I discovered that the flavour of sake was intrinsically linked to the regional environment, culture and cuisine. For me, the geography of Japan is a great road map to understand how sake can be paired with local food.

In the Northern areas of Japan, which have frigid winters and heavy snowfall, the sake flavour profile is generally light, tight and delicately sweet, but as you move south west, where the temperature is warmer, the flavour profile becomes richer, fuller and more powerful. For example, if you travel to the north eastern prefecture of Akita, the local Hinai chicken and ibburigako (smoke dried daikon) pair perfectly with the gentle sweet umami flavour of the local sake. If you go to the south western prefecture of Hyogo, which is probably most best known overseas for its wagyu beef (Kobe, Tajima, Sanda, etc..), the local sake tends to be umami-rich, complex and punchy.

For me, the geography of Japan is a great road map to understand how sake can be paired with local food.

Furthermore, in mountainous areas, people traditionally dried, smoked and fermented their food to preserve it during the long winter months, so they preferred to drink sweet, umami rich sake to match the robust flavour of the local cuisine. Whereas in coastal areas, where locals had access to fresh fish and vegetables all year round, they preferred a light and crisp style of sake.

So when you travel around Japan, I recommend paying attention to how well the locally produced sake matches the cuisine or ingredients of the region.

You will probably be surprised to hear that sushi restaurants in Japan generally have a limited sake selection – which is quite different to what you experience overseas. The reason being that sushi restaurants here are typically very small, and the limited refrigerator space is prioritised for the seafood. However, I highly recommend the counters of Mitani (三谷), Sugita (日本橋蛎殻町すぎた) and Ebisu Endō (恵比寿えんどう) for tour de force sake and sushi experiences in Tokyo. The chefs have phenomenal palates and personally select the sake for each course.

What are the current trends in the world of sake?

In recent years, there’s been a renaissance of traditional brewing techniques such as the kimoto method [a labour-intensive method of fermentation starter that involves the production of natural lactic acid by pounding the steamed rice into a paste] and the use of ki-oke (cedar tanks) during brewing. As with most agricultural products around the world, there’s been a real boom in the use of organically grown rice, and many breweries have become more pro-actively involved in the cultivation of local rice, too. Over the past 5 years, there’s also been a consistent trend towards making sake with a lower ABV. There are more and more 12%~14% ABV sakes appearing on the market — generally easy-to-drink styles that are popular with a younger generation of consumer.

Another style that’s been gaining popularity recently is sparkling sake. This is a fairly new genre in the sake world, but the quality is improving each year as brewers continue to refine their techniques. It’s very difficult to make sparkling sake, so some brewers have actually spent time learning from the great vintners of Champagne and have adapted the “Méthode Champenoise” to suit sake. I think this style in particular has great potential in the international market.

For sake to be able to feature on the menus of the top restaurants, or to become a mainstream choice for consumers in both Japan and around the world, we first need to ensure that it arrives at its final destination with the genuine quality and flavour that the brewer intended.

There are more and more western restaurants around the world introducing sake in their menus. Do you think that sake will become as mainstream as wine?

I’m very much hoping so, because it would be a dream come true to be able to enjoy both sake and wine at my favourite restaurants around the world. I personally love transitioning between champagne, sake and wine during the course of a meal. However, in order for that dream to become a reality, there is much that needs to be done in terms of education and improving the way that sake is stored, transported and handled overseas. Because, to be quite honest, the condition of the sake that’s reaching the international consumer is sub-par in my experience.

And finally, what about the distribution of sake around the world and how it’s sold?

As I mentioned, for sake to be able to feature on the menus of the top restaurants, or to become a mainstream choice for consumers in both Japan and around the world, we first need to ensure that it arrives at its final destination with the genuine quality and flavour that the brewer intended. To do this, we need to overcome fundamental cold-chain logistic issues and lack of knowledge about how to best store, serve and enjoy sake. And that’s basically what we are doing at Japan Craft Sake Company.

In 2017, we established a -5ºC cold-chain export system with our distribution partners in several Asian countries. Last year, we reinforced our export network with Sake Blockchain logistics, which ensures that each individual bottle of sake can be distributed in a transparent, traceable, genuine quality assured -5ºC cool-chain system from the brewery to end consumers around the world. Currently, sake distribution is opaque both in Japan and overseas, which means that the system is rife with unauthorised resales and even counterfeits. But the Sake Blockchain system allows all players to check the provenance of each bottle; what temperature it was shipped and stored at, what restaurant it’s being sold at, and even the restaurant’s refrigerator temperature and menu price. In addition, we assist breweries to develop marketing strategies and brand guidelines, as well as educational material and product information to elevate positioning and awareness of their products overseas. At the moment, our export system is being used by official distribution partners in Hong Kong, China, South Korea and Taiwan, but we plan to make the Sake Blockchain system available to all of the nation’s sake producers and their distribution channels in the future.

There are many amazing sommeliers, importers and educators around the world, like Pablo Alomar Salvioni, who are working so hard to create new and exciting markets for sake. To support their efforts, and ensure the sustainable, long-term growth of the sake market overseas, it’s essential that these systemic issues are resolved. Ultimately, it’s a win-win situation for everyone if sake can finally be enjoyed in its genuine condition anywhere around the world.

Rebekah’s top 5 Sakes

Aramasa Shuzō・Akita

Aramasa

Amaneko

Aramasa has amassed a cult-like following for its experimental spirit. All its sake is brewed in koike (cedar tanks) using Aramasa’s unique kimoto method, and rice that’s cultivated in the brewery’s own fields.

Amaneko is the most unique of the Aramasa range. It is brewed using white kōji (traditionally used to produce shōchu) which has a robust acidity, in addition to the usual sake kōji, giving it a piquancy that is quite unlike any other sake.

Perfect for enjoying with raw shellfish, butter sautéed seafood, and lightly seasoned fried dishes such as fritto misto and tempura. It’s citrus- like acidity and lactic notes are also superb with creamy sauces and soft cheese.

Takagi Brewery・Yamagata

Juyondai

Gold Label

Juyondai is revered for its refined sweetness and rich, complex flavour that is comparable to the world’s finest wines. It is so highly prized by connoisseurs that it is the most difficult sake to buy in Japan.

Gold Label is the crown jewel of the Juyondai International Collection, which is exclusively exported through -5ºC SAKE Blockchain logistics and sold by authorised distributors. This limited edition sake is the supreme representation of the beauty and exquisite craftsmanship of Takagi Brewery.

The perfect accompaniment to richly flavoured dishes such as buttery white fish, crab, braised abalone, and lightly seasoned poultry dishes.

Yamanashi Meijō・Yamanashi

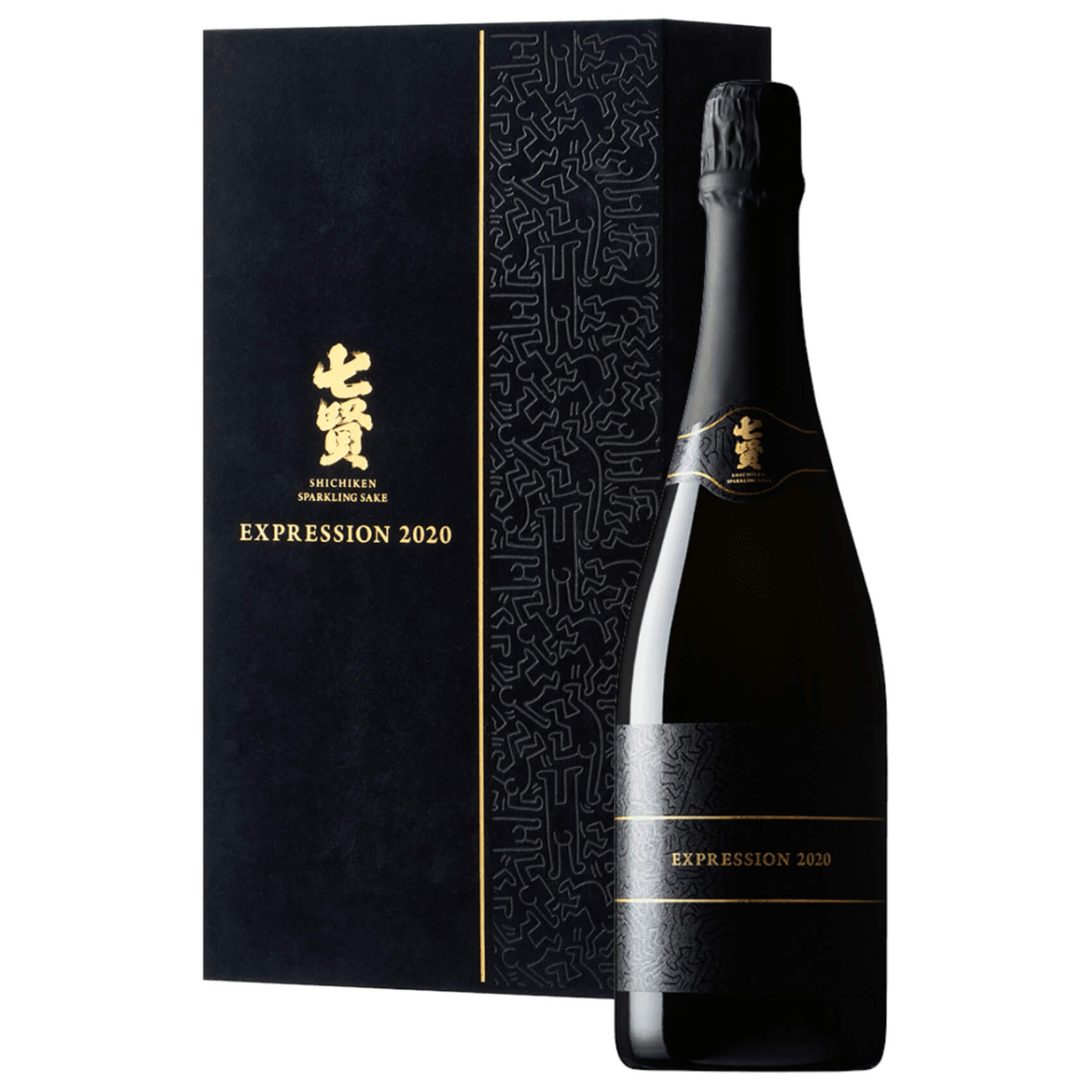

Shichiken

Expression 2020

The historic family brewery Yamanashi Meijō is now led by two young brothers who have taken “Shichiken” from a relatively unknown brand to a rising super-star in the sake world and a leader in the relatively new genre of sparkling sake.

A 40-year-old daiginjō koshu (aged sake) was brewed to create the “kijoshu” sake base of the extraordinary “Expression 2020”, which features artwork by the Keith Haring Foundation. Prepared with the “Méthode Traditionelle” technique of secondary fermentation in the bottle, along with a blend of classic and modern yeast, this rare sparkling sake is a triumph of creativity and innovation!

Kiyashō Shuzō・Mie

Jikon

Senbon Nishiki Junmai Ginjō

Jikon is not only superbly crafted sake, it’s simply delicious and easy to enjoy. Each year, I eagerly await the release of its Senbon Nishiki Junmai Ginjō ― the harmonious arrangement of its delightful aroma and charming flavour is just perfection! The expression on the palate is smooth and elegant, yet it also has complexity and precision.

Ideal for pairing with the aromatic, herbaceous flavours of Vietnamese and Thai cuisine, fresh cheeses, pecorino, and chèvre.

Maruo Shuzō・Kagawa

Yorokobi Gaijin

Akaiwa Ōmachi (Muroka Nama Genshu)

Yamahai Junmai

Located in the Sanuki region of Kagawa, the birthplace of udon, Maruo Shuzō has a legendary status in the sake world. They brew jizake – local sake for local people – and the locals of this area prefer a robust, umami rich flavour that suits the punchy flavour of the local cuisine.

All of their powerfully flavoured Yorokobi Gaijin sake is junmai style, and is muroka (non-charcoal filtered), nama (unpasteurised) and genshu (undiluted). They release half of their production each year, and the rest is aged for up to 3 or 5 years to intensify the flavour. The Akaiwa Omachi has a deep, umami-driven flavour and juicy acidity with herbal accents that reverberate in the long finish. Enjoy warmed (around 40ºC) or at room temperature in a Bordeaux glass with lamb, beef and game dishes … or udon!

The post An Exploration of Japanese Sake with Rebekah Wilson-Lye appeared first on Luxeat.