And You Don’t Stop

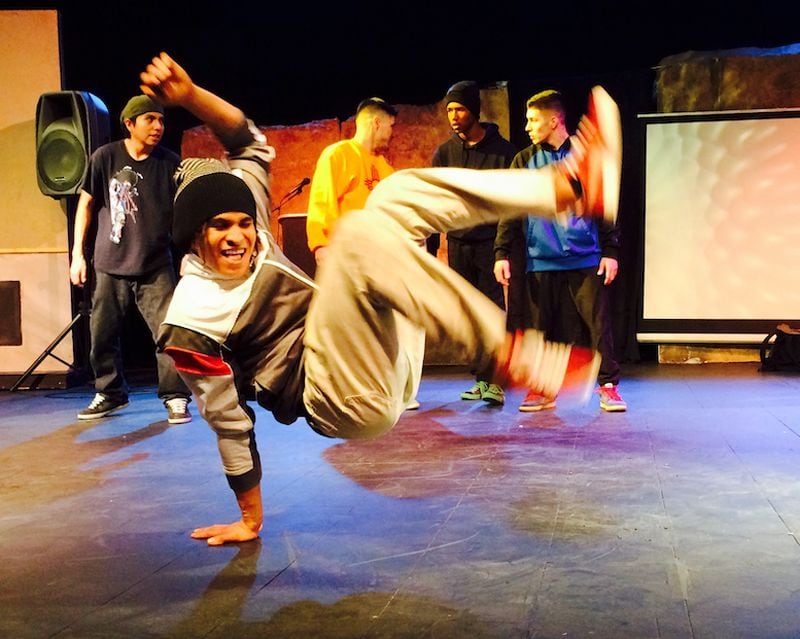

Twelve-year-old -breakdancer Ricky Rodriguez Jr. is literally upside down inside a space at the New Mexico School for the Arts campus, which formerly housed op.cit books. The hardwood seems custom-made for dance and, nearby, bass thumps from a speaker connected to an MP3 player.

“They say they have an ultrasound picture of me doing handstands,” he says.

Ricky Rodriguez Jr. (Alex De Vore /)

Rodriguez’s father and the rest of the 3HC breakdance crew’s leadership watch on as Little Ricky, as they call him, busts a series of moves to the music—impressive for anyone, let alone a kid who hasn’t quite hit junior high yet.

A few weeks earlier on June 19, as locals packed the Plaza in droves for the Juneteenth Love & Happiness event—one of the first public affairs after the long, cold lockdowns—3HC arrived on the scene to perform windmills, flares, head spins and hand hops. Mouths agape, the concertgoers simply watched, abandoning their own dance moves in sheer wonder. These days it’s rarer to see the crew take to the streets like that, what with the pandemic and all—but even as the world around them has shifted and evolved, one can always be sure Ricky Rodriguez Sr., Alejandra Avila and Tyrone Clemons will be breaking somewhere.

A staple in the dance scene since the ’90s, 3HC’s core has certainly changed over the years, but in its current incarnation, featuring Rodriguez Sr., Clemons and Avila as its guiding members, the crew has become a dedicated and nigh unstoppable force of dance. For Juneteenth on the Plaza, the trio was on fire, and someplace between the music from DJs D-Monic, Sol, Raashan Ahmad and others, the crowd learned exactly why the art of breakdance has risen and endured parallel to the establishment and rise of hip-hop itself—arguably the most important and innovative genre active today.

Ricky Rodriguez Sr. (Alex De Vore/)

In Santa Fe, breakdancing has ebbed and flowed with the years and health orders. But for those who’ve been to the shows or workshops at Warehouse 21 or to the downtown concerts or even just strolled through the Plaza now and again, 3HC members have kept the beat alive by endlessly honing their own craft, training up new generations of breakers and, during the height of COVID-19, founding and operating the Hip-Hop University project, a combination dance, arts and education program for youths grappling with inactivity, an uncertain future, and a town that has not always embraced them as its most vulnerable and underserved denizens.

But let’s take it back to 1997 and the Hopewell/Mann area of Santa Fe’s Midtown, when a young Ricky Rodriguez first glimpsed the short-lived but impactful Harambe rave and dance venue on the Southside.

“They used to pick up kids from the neighborhood, and I was just one of the kids,” Rodriguez tells SFR. “It was a bad neighborhood, but with a lot of energy, and I think Harambe’s thing was to go to the worst area that had the kids nobody wanted. I was in sixth grade.”

Harambe, the Swahili word for “all together,” was basically a warehouse—another in a long line of DIY spaces in Santa Fe run by people who took a look around and realized they could access the kind of cultures they desired simply by doing the work. In the few short years Harambe operated on the Southside, dancing, concerts and raves from the legendary Cosmic Kidz collective gave wayward youths something to do.

Rodriguez was instantly hooked.

“What really had me intrigued was the rave scene,” he recalls. “If you can imagine being in sixth grade and being at a rave....I never knew people were partying that way.”

Rodriguez says he’s suffered from an overabundance of energy since he was young. In those days, however, there wasn’t really talk of steps to address it—instead, the prevailing wisdom was something or other about shutting kids up. Finding rave and dance culture finally gave Rodriguez an outlet, even if Haramabe itself only lasted another two or three years. Still, the lessons stuck, particularly 3HC (itself an acronym for Harambe Hip-Hop Crew), and Rodriguez has held onto the dance tenets ever since.

“The impact it had in those years was permanent,” Rodriguez notes of the parties he started promoting. He translated those skills to a position at the Boys & Girls Club and, later, event promotion at now-defunct teen arts center Warehouse 21 and a position teaching dance at nonprofit Moving Arts Española.

“They all loved me because I could pull in the numbers” at events, he says. “They’d all trip out because I’d say, ‘It has to be free.’”

All the while, Rodriguez was sharpening his own breakdance skills, both with earlier members of the 3HC and on his own. Something clicked in his mind—a way to transform hyperactivity into hyper-productivity; he remembered what it was to be that forgotten kid from the so-called bad neighborhood and, as he trained, he built his own curriculum and phased into teaching. That, he says, is when he “got good” and started traveling around the country to compete.

“I spent every penny, I was broke all the time—it’s like a decision to live like a monk,” he tells SFR. “It’s a spiritual journey, though, and you’re trying to win battles, trying to win money. I’ve won thousands [of dollars]; I’ve won over 50 battles in my lifetime.”

Still, excellently awesome imagery of the roaming martial arts monk aside, Rodriguez says, “It’s addictive, but at the end of the day, it’s where you come from. So you come back and put together your own vibe, and that brings meaning to what you do.”

These days, Rodriguez is almost like the unofficial leader of 3HC, but only by virtue of his lengthier experience. The crew is ultimately a democracy, and everyone involved strengthens its core ethos.

Tyrone “Faro” Clemons, for example, brings his own acrobatic flair to the crew. A native of Española, Clemons connected with Rodriguez through Moving Arts when he was 15.

Tyrone “Faro” Clemons (Alex De Vore/)

“My dad was from Compton and he used to play hip-hop all the time when I was a kid,” Clemons says. “Tupac, Biggie, Geto Boys—I didn’t even know what it was, but I liked it.”

Underserved in his teens, Clemons says, he ended up at a boot camp for youths.

“I was the youngest person in the company,” he notes, “and I couldn’t get into the military like I wanted to. So, I had this floating period where I didn’t have anything to do until I was inspired to dance. It was either petition the military to let me in at my age—which I was ready to do—or dance. Something called me toward dance.”

A couple months after completing the boot camp program, Clemons found himself sleeping on Rodriguez’s couch and, later, they’d work together at Moving Arts Española.

Moving Arts “gave me a scholarship to go to Santa Fe for this [dance program] Moving People,” he recalls. “For me, coming from Española, that was like an invitation to Juilliard. In Española everybody told me I was going to end up dead or in jail. When I got out of boot camp, I wanted to beat that statistic.”

Clemons is married to 3HC member Alejandra Avila, who developed her own style during years spent studying modern dance and classical ballet. Her introduction to movement came from a youth dance drill team when she was 5.

Alejandra Avila (Alex De Vore/)

“It was kind of like those dance competitions in high school,” she says. “Then I got into high school and started taking dance more seriously.”

Avila earned a spot at the New Mexico School for the Arts, where guest breakdancing instructors from Moving Arts introduced her to breaking. As it was with Rodriguez, the connection was immediate. Still, Avila caught the eye of famed master ballet instructor Sheila Rozann, who teaches at the school during the year—an amazing thing, given Rozann’s broader contributions to dance education itself.

Avila says Rozann offered a full-ride scholarship to study at her Ballet Chicago school in Illinois, though Avila didn’t wind up pursuing that opportunity.

“Which isn’t to say I did or have given up modern dance, just that I feel like I haven’t done everything I wanted to do with breaking,” Avila explains. “I never quite felt like I belonged [in ballet]. It was like I was trying to break out of a lot of stories about how the little Mexican girl couldn’t do it. Once I found out what I could do with breaking, I leaned more toward that. Ballet and modern dance did save me, but with breaking, I had more of a place there—breaking changed my mentality to be more positive, and I felt like it was only right for me to give that back to the community, especially in New Mexico.”

Much of that giving back has come in the form of teaching, though with a style rooted in ballet and modern dance, Avila’s prowess is unlike that of most breakers. And when the pandemic hit and she saw the mass pivot to online learning, she knew she had to do something. Hip-Hop University was born.

“I wanted to keep the dance community alive,” she tells SFR. “I wanted to say, ‘You’re not isolated, we can get through this whole thing together.’”

Hip-Hop University began exceeding Avila’s expectations even before it officially launched. She had pictured a bit of dance instruction and maybe some art lessons, but a large number of local culture, dance and educator types showed up in a major way, resulting in not only dance lessons, but workshops in poetry, comic book creation, illustration, style writing and bedroom-based music production, as well as a homework helpline run by local high school teachers who moonlight in the B-Boy/B-Girl world.

If you’ve unsure whether you’ve seen Tyrone “Faro” Clemons dance, don’t be—you’d remember. (Courtesy Ana Gallegos y Reinhardt/)

“Every week we had a free workshop, and then, like with our Intro to Breaking Class, we’d do a followup, so some of them were doubled,” Avila says. “It blew my mind that it grew so big, and it was beautiful to bring together all of these different scenes in New Mexico—we have our breaking scene in Santa Fe, but to connect with [hip-hop outfit] Outstanding Citizens Collective, graffiti artists in Albuquerque, dancers from Carlsbad...it ended up becoming a bridge to unite different parts of New Mexico.”

Avila says Hip-Hop University served students from California and Texas, as well as Uganda and Germany, and was such a resounding success that the ideas for the next round have been plentiful. The program is on hiatus for the summer, but Avila has been holding meetings to plot out classes and workshops for the upcoming iteration and says she hopes to garner financial, political and practical assistance in the meantime.

We can reportedly expect more solid announcements soon, but Avila says an October start date is likely.

“We don’t want to rush, and we also want to give any of the kids some time to adapt to going back to school,” she says. “We know having to be online last year and then having to go back this year will take some time.”

Without over-promising, Avila can reveal Hip-Hop University will see returning local instructors such as Rodriguez and Clemons—the latter of whom will also lead workshops in comic book character and layout design—as well as DJ classes with DJs Mark Boogie and Suani Smooth, perspective drawing with Albert Rosales, style writing with Erhen Kee Natay, poetry with Nolan Eskeets and tutoring assistance from local educator Alicia Gonzales, among others. Avila will teach the Intro to Breaking workshops and, she says, other classes may be added before October rolls around, depending on what kind of support the crew receives.

Of particularly sad note, however, is the recent death of Hip-Hop University instructor and longtime 3HC collaborator Colin White, who taught popping during the last run of classes.

“We know he’s dancing in another place,” Rodriguez notes. “Even though he’s gone, that connection goes beyond life and death.”

Avila says much of what 3HC does next will happen in memory of White. His death, she says, pushes the crew harder.

“I think it’s a human thing to want to be part of something,” she says. “This next generation...they’re ready to express themselves and I’m excited to see what happens next. When I was a kid, I really hung out with the wrong people and did the wrong things. I thought that’s what I was supposed to do. If I hadn’t found dancing, I’d definitely be in trouble. In jail. Dead. Hip-hop saved me.”

Clemons agrees.

“It saves your life,” he adds. “Instead of me walking in somewhere, feeling scared, you get the feeling of what it is to be dedicated.”

Rodriguez Sr. knows a thing or two about dedication. Having taught hundreds of people at this point, he tells SFR that whenever he’s doing pretty much anything, he pictures himself doing windmills and handstands; pulling off flips and pouring his entire being into breaking.

“I think it’s sacrificial,” he concludes. “We’re going to be hurting tomorrow when we go to work, but it’s so extra.”

To find out more about Hip-Hop University, including how to donate, visit facebook.com/hiphopuniversitynm

Breakdance Glossary

It’s all well and good to think you know what breakdancing actually looks like, but knowing the terminology is a great way to deepen one’s appreciation. This is not even close to a complete list, but it is a handy overview. Remember that safety comes first, and if you really want to get into the sweetest breakdance moves, the 3HC breakdance crew would be more than happy to welcome you into the fold.

The Windmill

This is probably the move you imagine when someone mentions breakdance. The dancer lies on the floor and spins their outstretched legs in a circle around themselves. You know—like a windmill. There are many ways to vary and build off of this basic technique.

The Flare

Arguably one of the more famous moves, the flare is that incredibly acrobatic maneuver wherein the dancer relies solely on their hands or elbows to swing their legs around themselves in a widespread circle.

The Hand Hop

Think of it like a handstand during which the dancer can literally use their hands to perform small hops. Word is, the move originated in the capoeira world of dance-fighting, and more experienced dancers can pull it off one-handed.

The Buddha Spin

You’ll need some pretty serious upper body strength to pull off this move wherein the dancer kneels and then, using their hands, lifts their body and alternates the weight-bearing hand while spinning in a circle.

The Boomerang

This one finds the dancer’s legs outstretched to either side, roughly in the shape of a boomerang, and the spins come from an alternating hand movement similar to the Buddha Spin.

The 1990

A spinning handstand that honestly looks so sick when done properly.