Andrea Marcolongo on How Running Fuels Her Creative Process

In my thirty-five years, only two things, aside from my mother, have delivered me into this world. Two things that haven’t changed my life, so to speak, as much as led me to understand life and, in the end, to live life.

The first was ancient Greek, encountered in the classrooms at my liceo classico when I was fourteen.

The second was running, encountered along the Seine at the end of summer three years ago.

It is about this second discovery—this epiphany, really—that I intend to talk. I’ve already said more than enough about the language of ancient Greece and don’t see a point in adding anything further; but if in this new tale of mine I bring it up now and again, it isn’t to inflict pain on the reader but to help me better understand and think through things, for I hope the comparison will shed light on how I currently feel about running, which can be described in a word: confused.

Nothing. That was the extent of my knowledge of running, or training, or jogging—call it what you will—when I put on a pair of running shoes for the first time. Absolutely zilch. And apart from a handful of totally unmemorable outings the same could apply to all my firsthand experiences in that parallel universe we call sports. As for secondhand experience, the passive enjoyment taken, as a spectator, in the human spectacle of competitive sports, I can boast of a bit more expertise, but, save for a curiosity in soccer as intermittent as it was willed and which compelled me to the stadium a couple times, it never amounted to more than that generic, universal sense of ennoblement and awe that comes over us when we watch the human body in motion while parked on the couch or in the bleachers.

We arrive at the first, surprising point of similarity between running and the path that led me to pick up an ancient Greek dictionary one day: I had absolutely no prior knowledge of either subject.And here we arrive at the first, surprising point of similarity between running and the path that led me to pick up an ancient Greek dictionary one day: I had absolutely no prior knowledge of either subject. Worse, before stumbling upon them, I barely suspected that Greek or running even deserved a prominent place in my boring existence.

To be clear, not only were there no Greek enthusiasts in my humble early life and family line, but there wasn’t a single distant relative who had graduated from a liceo classico—nothing too Dickensian there, it’s just the way it was: this is why public school education is important. Strange, it only now occurs to me that the shortage of humanists in my household was equal to the shortage of athletes: aside from the obligatory bicycle given to me as a present when I was about eight, I don’t remember ever having seen sports equipment being carried into our house, nor did it cross my mind to demand any.

Somehow, I made the two discoveries independently and in my modestly pioneering way. In both cases, it fell to me to seek them out in what until then had been terra incognita.

The one, not insignificant difference is that, when I got it into my head to learn the Greek alphabet, I had at my back the wind of someone newly out of swaddling clothes. Whereas when I put on a pair of sneakers for the first time, that wind was about to abate for good.

The outcome of these two discoveries, in any case, is identical: despite my ardor and determination, I remain a dilettante in both fields. At the age of 35, I have neither a doctorate in classical philology to display nor medals to show off the finishing lines my legs have carried me across. For years I publicly proclaimed my love and dedication until I was out of breath, yet in both arenas, Greek and running, I am still way behind the professional and competitive curve.

In all honesty, and with all the severity-verging-on-cruelty with which I tend to evaluate my achievements, I know that my propensity for dilettantism can’t be ascribed to weakness or laziness—not to them alone, anyways. I think it’s more a consequence of the profession that I’ve chosen in life, which is to say writing. Whenever something really captures my interest, I almost never see it through to the end, out of some perverse need to leave it unfinished, so that I torture myself over my shaky grasp of it yet at the same time take pleasure in writing about it.

It only now occurs to me that the shortage of humanists in my household was equal to the shortage of athletesIt’s not that I lack skills in ancient Greek or strength in my calves. And I don’t believe, as Plato writes about sports, that I have ever shrunk from a war or battle, at least not the personal kind. But I have to admit that I would never have written a book about Greek grammar had I had the courage to become a professor, nor would I ever have written about running had I ever completed a marathon.

That must be the reason I run and write: to put off completion. Another form of cowardice.

*

Carefully planning my daily workouts, which I hope will lead to my first marathon, I realized to my shock that I’m not quite sure why for the last few years I’ve insisted on lacing up my running shoes.

If for me writing represents an urge, an obsessive need to understand, and I know no other way to arrive at understanding than by lining up words which soon give way to sentences, chapters, and finally a whole book, I’m still not sure whether running comes as naturally.

Then one day, thinking more deeply about my apparent lack of firm reasons for running, I became aware that for me the act has something to do with my terror of aging.

I finally understood, I think, that I keep running because it is the most concrete and effective way for me to feel alive, or at least the one way I know.

In other words, I run because I’m afraid of dying.

To prove to myself that I’m alive, not just biologically but fully alive—emotionally, physically, spiritually—I know various activities, most of them quite pleasurable: being in love, going to an art exhibit, reading a good book, white wine on a balcony in the summer, the cool smell of fresh snow. Yet, however sublime, these interests don’t make my heart “skip.” They make me happy, but they don’t actually increase my heart rate much.

Whenever something really captures my interest, I almost never see it through to the end.I’m generally not a fan of brief, heart-pounding, adrenaline-boosting thrills, whether it’s extreme sports or drugs or horror movies. They’re not my thing. So, by default, and maybe due to cowardice, the one activity that I know of and routinely perform to get my heartrate over its normal resting rate, otherwise known as taking that metaphorical break from life, is running.

Yet when I run, I’m not taking a break from life; I’m living.

I feel it with a precision and concreteness that, prior to running, was totally unknown to me, and which even the most sublime mental activities fail to generate.

The life instinct that I feel when I run isn’t cerebral, or confined to my head, or intimately poetic. It’s not the (often bitter) fruit of my thoughts. When I run, I’m alive, doing what I was programmed to do: moving and pushing my body to its maximum physical potential. It’s objective and observable, and it can easily be measured by the tools of science.

The blood pulsing in my veins and temples, the heart—suddenly audible, almost raucous—that magically falls into sync with my feet hitting the pavement, the muscles that warm up, resisted at first and then happily surrendered to, all do the job they were made to do; running, my body performs every miraculous function for which it exists—nothing more.

That’s life: tangible, mine. Indeed, I’m its spitting image, life itself, the celebration of every function written in my genetic code.

Every time I go for a run, long or short, my body and, by some miracle, my head along with it—that’s what runners mean when they talk about “mental health”—does everything in its power to reach its one goal: to live life to the fullest, or at least far more than my body is permitted to when it’s planted in a chair. My heart beats as fast as it can; my muscles contract as much as they can; my vascular system pumps as hard as it can; my brain, free of abstract thoughts, coordinates everything; my lungs swap carbon dioxide for oxygen. My whole body fulfills the duty that the DNA in every single cell demands. Not an action more, not an action less—and therefore everything.

When I run, I’m alive, doing what I was programmed to do: moving and pushing my body to its maximum physical potential.It’s because of this biological and emotional sense of wholeness that when you run you’re alive for once, complete for once.

Sometimes even immortal.

In fact, running is the best antidote to my fear of dying. It’s the tangible proof, the stamp that demonstrates that, for today, and at least until tomorrow, I’m still in good health, still alive.

*

Ever since I was first taken with the idea to write about running, one thing has proved undeniable: running has become more and more of a burden. I enjoy it a lot less, and I need it a lot more.

It’s as though running has spilled over into every aspect of my life, and I can’t stand it anymore. Not only has running hijacked all my conversations, not only do my friends keep asking me about the marathon in Athens, not only do I do nothing but read books and articles about it, but worst of all, running has gotten in the way of my writing, and vice versa, in a vicious and exhausting circle that I don’t know how to break.

If I got out for a run, it’s to think about running and then write about it. Once I’ve written, I have no energy left and need to go out for another run to find new inspiration for the story I’m working on. Running had once been my escape from obligations and thoughts, a freedom I never shared with anybody; now the street has become my notebook where I jot down ideas that I’ll soon share with readers.

There are days, like this morning, when the American accent of my mindfulness coach blasting through my earbuds does the trick and I arrive home reinvigorated, buoyed a bit, ready to sit down and write again. Then there are days when I feel like hurling the podcast and its Zen wisdom, along with whatever I’m writing, into the Seine.

My restlessness must be a product of inexperience. I’ve never been so free on the page, so open, so far afield from my previous work, and I’ve not even run a marathon yet. In my darker moments, I alternate between dreams of giving up writing for good once I’m done with this project and dreams of giving up running, or both.

For now, I’m hanging in there, I think. I go out to run so that I can write, and I write so that I can run. It sounds funny, but that is my life at the moment, and like everybody I’m doing my best to keep my balance.

–Translated by Will Schutt

___________________________________

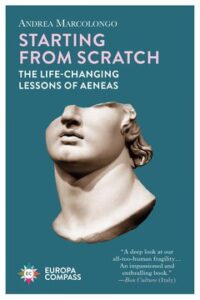

Starting From Scratch: The Life-Changing Lessons of Aeneas by Andrea Marcolongo, translated by Will Schutt, is available from Europa Editions.