Anna Quindlen on the Power of Writing by Hand

The following is excerpted from Write for Your Life and a version first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

*

It’s challenging to develop a sense of connection to one of the notorious robber barons of the nineteenth century. But I have to admit to being intrigued by John Pierpont Morgan, generally known as J.P., despite the photographic portrait by Edward Steichen that makes him look as though he would happily run you down with one of the locomotives in his railroad empire. Morgan was a leader of the Episcopal Church and a devoted yachtsman; he, or some version of him, appears as Rich Uncle Pennybags in the Monopoly game, luxurious mustache and all. No question he was in many ways what we call a piece of work.

But he was also a great collector. A lot of those rich guys with waistcoats and watch fobs, stern and mustachioed in their oil portraits, collected things, but they were what I think of as dumb things, things that someone told them they should want, perhaps someone from England or France whose lineage and accent made those collectors feel fraudulent. Snuffboxes, epergnes. Are you familiar with the epergne? Don’t worry, no need.

Morgan was different. He loved important words on the page. He collected handwritten documents and manuscripts. Of Elizabeth I of England, Voltaire, and Isaac Newton. Of Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Jane Austen. He acquired the only surviving manuscript of Paradise Lost. And of A Christmas Carol. The tale of Ebenezer Scrooge and the three spirits who turn him from a bad man into a good man in the space of a single night may be the best-known Dickens from a popular standpoint, but it’s not the best: Bleak House is. Still, it has become a bit of a touchstone for my children because, for as long as they can remember, A Christmas Carol has been read aloud on Christmas Eve in their household. I get the last chapter, so I get to be Tiny Tim and say, “God bless us, every one!” to end the reading.

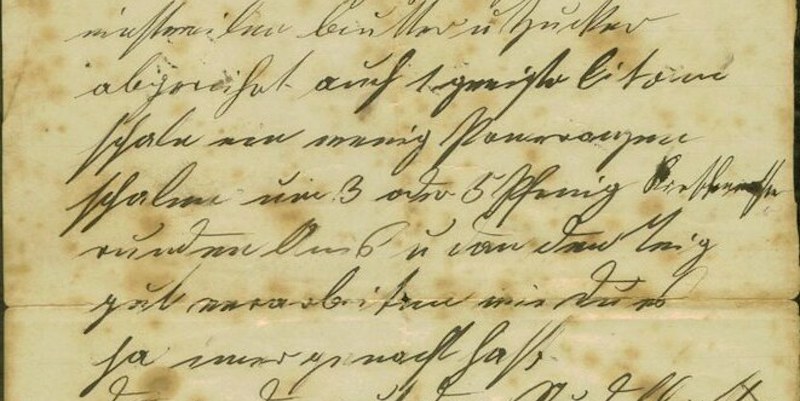

The manuscript, which is in the Morgan Library in New York City, is really something else. It’s not simply that Scrooge, the Cratchits, and the Fezziwigs live in it; it’s that Dickens does. In heavy-handed black ink he pushes forward on unlined paper, something about his script suggesting speed, or perhaps it’s just that I know he wrote the book in six weeks. It’s a bit terrifying to consider that this was the only copy of the novella. A fire? A flood? A disaster.

It is humbling to see how much crossing out Dickens did, how much rewriting and cutting. It reminds you of what we will never see of the work of some modern novelists, whose revisions are sanded from the rough wood of the first draft by the overwriting on the computer. The rough wood is in this manuscript; the overwriting overwhelms. The novelist John Mortimer wrote of “the obliterations achieved by a sort of undulating scrawl, patterned like the waves on the sea.” They are everywhere. Dickens wrote, and was dissatisfied with his writing, and wrote again, and expunged with a heavy hand, so that it is nearly impossible to see what was there in the first place.

I wonder: Was Dickens, already famous at the time, safeguarding the possibility that someone might think to produce, or at least study, a first imperfect draft of his work? Some writers cover their tracks, burn their letters. They’re not simply writing for you, or themselves, but for posterity. They don’t want readers to know how they did what they did any more than the magician wants you to know how the handkerchief became the dove. Was Dickens one such?

There it is: In looking at the handwriting, the manuscript, the crossing out, I imagine the man. And there’s a simple truth. Something written by hand brings a singular human presence that the typewriter or the computer cannot confer. There’s plenty of good writing done that way, but when you simply glance at the page, it could be the work of anyone. But when you’ve written something by hand, the only person who could have done it is you. It’s unmistakable you wrote this, touched it, laid hands and eyes upon it. Something written by hand is a piece of your personality on paper. Typed words are not a fair swap for handwriting, for what is, in a way, a little relic of you. Why do we even know the name John Hancock, among all the signatories of the Declaration of Independence? Because he signed in handwriting so florid that it has become a catchphrase for signing your name.

My grandmother’s handwriting was as gracious as a curtsy, and every bit as stylized.There are still many people, even many writers, who write by hand. At the outset of his memoirs President Barack Obama described working with a yellow legal pad and a roller-ball pen. “I still like writing things out in longhand, finding that a computer gives even my roughest drafts too smooth a gloss and lends half-baked thoughts the mask of tidiness,” he wrote.

Jennifer Egan, a novelist who has won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, says she, too, writes in longhand on legal pads, “because it seems to do a much better job of unlocking my unconscious, which is where the good ideas all seem to be.” Then she types it all into her computer without rewriting, makes an outline after reading it over, rewrites by hand on the hard copy, then enters the rewrites in the computer to generate a new draft. (Although, she feels obliged to add, her penmanship “is dreadful—in fact my writing is very hard for even me to read, and that seems to work in favor of the method I’ve described above, because it makes the writing process literally blind.”)

“I’m grateful that I learned script,” she says, “as so many kids do not today, because I wouldn’t have the flow to use this method otherwise.”

The novelist Mary Gordon has a stockpile of new notebooks that she suspects she may not live long enough to deplete entirely. “I feel like the rhythm of the words gets mirrored in the movement of my hand and the speed of my blood. And it slows me down, which is a good thing,” she says. Then she types into the computer, and completely retypes for every subsequent draft. In her case the penmanship is excellent: “I went to Catholic school,” she says with no need for further explanation. She knows that fewer and fewer writers work as she does, and that the computer will leave fewer traces of the process of revision for writers to come, and for the institutions that traditionally have stored their papers for posterity. “At some point there won’t be any papers,” Gordon says. “There aren’t going to be any drafts. They will disappear inside the computer.”

My father had a file with the word “Funeral” written by hand on the tab. It was in the file cabinet between Expenses and Gas Mileage. With some regularity he would pull it out and show it to me, usually because of amendments. The wake was deleted after he attended one that he said was like a cocktail party with a coffin as the centerpiece. The burial went out in favor of cremation and scattering at sea, despite the fact that that would leave an empty space between his two wives in the cemetery. He shrugged when I brought that up. “Things change, baby,” he said.

In the last two years of his life, although he wasn’t conspicuously ill, he made me take the file from the file cabinet and, as he said, “hang on to it.” For the last two weeks of his life I kept it in my purse. The morning of his death I laid it next to the phone. It was a godsend, the Stations of the Cross of bereavement—funeral home, church, readings at Mass, location of repast—all spelled out so that I didn’t have to think, I merely had to do. I quietly mocked it when he was alive; I clung to it when he was dead. He even wrote his own obituary. “Publish as written,” it said in the margin.

That file is now in my file cabinets, but it’s not between anything. It’s the first thing in one particular drawer, although I no longer have any use for the phone number of the funeral home in Cedarville or the lyrics to “Danny Boy,” which I knew even without a song sheet. It’s there for the simple reason that it’s in my father’s very strong and specific handwriting. His fingers guided the pen, made these words. Even though his ashes are long gone into the Delaware Bay, this document bespeaks his very existence. So do my mother’s words in black India ink, memorialized by my sister when she had them framed between the old his-and-hers wedding portraits for my elder son and his wife. “Wedding bells,” it says, “June 1951,” with a little sketch of a pair of bells from the woman who wanted to be an artist. I stop and look at that tiny bit every time I pass it. Prudence Quindlen was here. She lived. There is the proof, in her own hand.

What constitutes our own hand has changed during my lifetime, and become generational. The requirement that cursive writing be taught in elementary schools was dropped in the United States in 2010. For those of us of a certain age, this is almost unthinkable. How many hours did we spend with our forearms flat on a faux-wood desktop while making loops and whorls with our pencils in the service of the Palmer method, developed by a man named Austin Palmer and relying on the muscles of the arm, not the hand or fingers, to produce uniform letters. The method was the standard for decades, and it did make for pretty penmanship. My grandmother’s handwriting was as gracious as a curtsy, and every bit as stylized. If you didn’t mention it, believe me, Kitty Quindlen did.

When the requirement to learn cursive was dropped, I suppose it made sense at a couple of different levels: For the technogeneration, words were generated by keyboards, not pens or pencils. And for some of their parents, there were surely unpleasant memories of endless days spent mastering the seamless curves and connections that would become an acceptable lowercase f or uppercase D.

And as cursive began to creep back in— many states reinstated the requirement in the decade after it had been dropped—it came with political undertones. Some conservative lawmakers complained that children who could not write cursive could not read it, and therefore would be unable to read the Declaration of Independence, apparently skipping over the fact that typescript versions are widely available. When lawmakers in Louisiana passed a bill requiring that cursive be taught in the schools, some shouted “America!” when it was approved, perhaps forgetting the America that made it a crime for enslaved men and women in that state to be taught to write at all.

Of course there have long been writers who did not write by hand. Nietzsche used a typewriter because his eyesight was going. Mark Twain was the first significant writer to hand in a typewritten manuscript, Life on the Mississippi, typed by his secretary. Henry James dictated directly to his secretary, perhaps because he may have had what we now know as carpal tunnel syndrome. His secretary swore that after his death she was still getting dictation from him, but nothing was ever published posthumously.

Still, some forms seem simply antithetical to typing. There’s a famous photograph of Sylvia Plath sitting on a stone wall, with a teeny little typewriter in her lap, and it looks preposterous, like an ill-wrought prop for a magazine shoot.

Poetry needs to be written by hand, doesn’t it? Rafael Campo, the doctor poet, thinks so. “That physical act is what makes a poem come alive,” he says. “And unlike other writing, a poem has a physical shape, a physical dimension on the page. It does not have the block arrangement of prose.” Maybe Plath used that teeny typewriter for her prose work. Her poetry is handwritten, writing that looks more like printing than cursive. The most interesting piece of it is the clean copy she made of the poem “Ariel” for fellow writer Al Alvarez. The poem is full of fury, but on the copy she made for Alvarez, at the bottom, Plath has drawn the kind of stylized little flower that young girls draw in their notebooks. It’s wildly inappropriate to the material but deeply reflective of the person, a good-girl coda to a crescendo of rage. All by itself it tells a story.

There are certain moments that cry out for the handwritten.Handwriting tells a story. In mystery novels threatening notes are almost always written in what is described as block print; cursive would give the game away. It is personal, identifiable. Julia Baird’s biography of Queen Victoria relies heavily on letters, and she says it is not only the prose but the penmanship that spoke to her. “I could see the emphatic punctuation points, the double underlining for emphasis, the second thoughts, the loops growing larger when writing carefully, and the letters flattening, becoming less legible when she was angry,” says the biographer. The queen spoke through her handwriting. The signature of Queen Elizabeth I, the brilliant, strong-minded monarch who faced plots and detractors because of her gender and the circumstances of her birth, is a remarkable tell, the z underlined with artistic curlicues, the b crowned with a flourish, the thing ended with something almost a colophon, a hybrid of a flower and a cross. It is the signature of someone who is Someone, and who wants to put the world on notice of that fact. Across centuries it speaks.

Handwriting is also intimate. There are certain moments that cry out for the handwritten. A condolence letter, for example, surely should be put down on paper by hand, no matter how bad your penmanship. Does a love letter read the same, feel the same, mean as much if it is typed? Over the years I have replied to many letters from readers, and one of the first things they mention when I meet them is not just that I wrote back but that I wrote By Hand, as though that were both more onerous and more thoughtful. And in a way I suppose it is. Writing by hand does slow you down, as Mary Gordon notes; it has to be deliberate, each letter a tiny thought process in itself.

This is one reason why Dinah Johnson started something called the Handwritten Letter Appreciation Society. “No gadgets or devices or anything electronic or mechanical that can go wrong,” she says. “There’s a quietness to it, no fuss.” She also says that a person’s handwriting conjures them up “like nothing else does (except perhaps their favorite worn-in shoes).” That intimacy, the personality of handwriting, may explain why people will stand for hours waiting to have a book signed by the author. Even if it is almost illegible, that pen stroke is evidence that there was a moment when you were face-to-face. Perhaps it doesn’t even matter what handwriting says, as long as it exists, a physical reflection of the life of a person. When I have looked at that manuscript in the Morgan Library, I stare and think, “Charles Dickens touched this, with his pen and with his hand.”

And in a completely different way, I feel that about the handwriting of those I love. I store away notes, cards, and school papers from my children not only for what they say but for the irrefutable individuality and age progression contained in the hand that wrote them. I so wish I had more of my mother than those two words in India ink, which are really printing, not her actual handwriting. If I close my eyes, I imagine I can see her handwriting. But it’s not the same as having paper that her pen has touched. It’s not the same.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Write for Your Life by Anna Quindlen, available via Random House.