Back to School (Part 8)

The 1950’s usher in a time of change. Springing from the influences of Gerald Mc Boing Boing, discussed last week, the progressive art styles of UPA begin to rock the foundations of traditional animation, leading even the most traditional of competing studios to run experiments in the flattened, progressive formats (some turning to same more as budgetary shortcuts than for purposes of expressive creativity). Also, animation has its first true brush with the difficult subject of juvenile delinquency, tackled by the last studio you would expect to deal with such a progressive and controversial topic – Terrytoons! Two of today’s batch also had the distinction of being nominated for Academy Awards, making today’s lesson of particular historic import to a study of the art.

The 1950’s usher in a time of change. Springing from the influences of Gerald Mc Boing Boing, discussed last week, the progressive art styles of UPA begin to rock the foundations of traditional animation, leading even the most traditional of competing studios to run experiments in the flattened, progressive formats (some turning to same more as budgetary shortcuts than for purposes of expressive creativity). Also, animation has its first true brush with the difficult subject of juvenile delinquency, tackled by the last studio you would expect to deal with such a progressive and controversial topic – Terrytoons! Two of today’s batch also had the distinction of being nominated for Academy Awards, making today’s lesson of particular historic import to a study of the art.

Madeline (UPA/Columbia, Jolly Frolics – 11/27/52 – Robert Cannon, dir.), would mark the first UPA adaptation of an outside literary work (“Boing Boing” was penned by Dr. Seuss for a Capitol record and not as a book, excepting a version in limited quantity eventually published in conjunction with the film itself). Though nominated for an Academy Award for its visual capturing of the illustration styles of the Ludwig Bemelmans work, I have never personally ranked this among the best of UPA’s productions (yes, I know that makes me unpopular), mainly because I kept waiting for a genuine plot to develop, but found to my dismay that there was essentially none in the original work or its adaptation. Taking place in a Catholic boarding school, we follow the daily lives of “twelve little girls in two straight lines”, supervised by a nun named Miss Clavelle. Backgrounds are atmospheric and colorful and are the main appeal of the short. However, despite describing traits of one little girl, Madeline, as the youngest, most daring, and not afraid of mice or tigers in the zoo, she really doesn’t get to do anything of plot-point worthiness in the story. All that happens is she wakes up crying one night, is sent to the hospital, and has her appendix removed. (I actually found this point disturbing on my first viewing of the film, as one doesn’t usually associate tbis problem with young children, so it seemed a bit heavy for a film obviously aimed at a young age bracket, especially when Madeline displays her scar. Couldn’t they have just had her have her tonsils out?) The other children, seeing the toys and flowers that have been sent to her (including a doll house from Papa, though the father is never seen, so assumably considers himself too important to take time off to visit his sick daughter himself (??)). All of them wake up Miss Clavelle the following night, begging to have their appendixes taken out too. A cute, but gruesome thought, which might have been more fitting for the offspring of Mr. and Mrs. J. Evil Scientist. It’s a tale that really doesn’t, at least to my tastes, have any appropriate target audience excepting children facing a serious operation – much in the same way that Mercury Records kept for many years in catalog an item known as “Peter Ponsil and his Tonsil.”

Madeline (UPA/Columbia, Jolly Frolics – 11/27/52 – Robert Cannon, dir.), would mark the first UPA adaptation of an outside literary work (“Boing Boing” was penned by Dr. Seuss for a Capitol record and not as a book, excepting a version in limited quantity eventually published in conjunction with the film itself). Though nominated for an Academy Award for its visual capturing of the illustration styles of the Ludwig Bemelmans work, I have never personally ranked this among the best of UPA’s productions (yes, I know that makes me unpopular), mainly because I kept waiting for a genuine plot to develop, but found to my dismay that there was essentially none in the original work or its adaptation. Taking place in a Catholic boarding school, we follow the daily lives of “twelve little girls in two straight lines”, supervised by a nun named Miss Clavelle. Backgrounds are atmospheric and colorful and are the main appeal of the short. However, despite describing traits of one little girl, Madeline, as the youngest, most daring, and not afraid of mice or tigers in the zoo, she really doesn’t get to do anything of plot-point worthiness in the story. All that happens is she wakes up crying one night, is sent to the hospital, and has her appendix removed. (I actually found this point disturbing on my first viewing of the film, as one doesn’t usually associate tbis problem with young children, so it seemed a bit heavy for a film obviously aimed at a young age bracket, especially when Madeline displays her scar. Couldn’t they have just had her have her tonsils out?) The other children, seeing the toys and flowers that have been sent to her (including a doll house from Papa, though the father is never seen, so assumably considers himself too important to take time off to visit his sick daughter himself (??)). All of them wake up Miss Clavelle the following night, begging to have their appendixes taken out too. A cute, but gruesome thought, which might have been more fitting for the offspring of Mr. and Mrs. J. Evil Scientist. It’s a tale that really doesn’t, at least to my tastes, have any appropriate target audience excepting children facing a serious operation – much in the same way that Mercury Records kept for many years in catalog an item known as “Peter Ponsil and his Tonsil.”

A cel and background from UPA’s “Madeline” (1952)

I will mention out of sequence, to get past the issue, that Gene Deitch’s Rembrandt Films picked up where UPA left off with a series of three shorts of its own based upon Bemelmans’ sequels to the book, Medeline’s Rescue (1959), Madeline and the Bad Hat (1960). and Madeline and the Gypsies (date unknown), which I believe were all directed by one V. Bedrick. I hace not seen all of them, and had to steel myself a bit to watch the first of them for the first time for the writing of this article, not knowing what to expect. I found myself pleasantly surprised. For one thing, nothing seems to be lost in the animation style, which again faithfully renders the book illustrations. What’s more, many of the scenes look like they’ve been archived right out of UPA’s “morgue”, repeating scenes for establishing shots and key repeated plot points that seem to be identical to shots in the UPA original. Even the visual storytelling style seems identical, with frequent use of cross-dissolves between sets, and certain visual pans performed identically. Only backgrounds and color choices are not of the same caliber, Rembrandt opting for less vibrant colors (which probably saved them a considerable amount in the price of paints). Where this film (and probably the underlying literary work) succeeds over and above the UPA vehicle is in presenting a genuine plot that is not disturbing. Madeline repeats her stunt from the original of scaring Miss Clavelle by balancing atop the railing of a bridge over the river – but this time she falls in. A stray dog leaps into the water, and performs a rescue. Madeline takes the dog back to the boarding school, where the kids adopt it, and name it Genevieve. All is well until a visit by the school’s board of trustees. A snooty trustee spies the dog under the children’s beds, and despite Miss Clavelle’s and the children’s pleading, chases the dog out of the school, claiming she is against the rules. Madeline stands up to the trustee, claiming that she and the dog will have their revenge. When the trustees leave, Miss Clavelle and the girls, in defiance of the trustees’ orders, search all over Paris for Genevieve, with no luck. They return empty handed to the school, and time passes. Miss Clavelle is awakened one night, to find to their surprise Genevieve at their front door, howling to be let in. The kids are overjoyed, and bicker over who will have the honor of having Genevieve sleep in their bed tonight. When Miss Clavelle enters to break up the argument, there is a surprise – Genevieve delivers a litter of pups – and now, on their next walk through Paris, there is enough hound to go around, with two straight lines of girls, and two additional straight lines of dogs! Now this kind of storytelling is more like it.

BELOW: The UPA Madeline (1952):

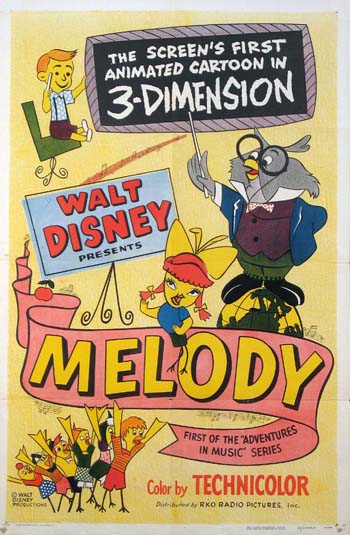

Melody (Disney/RKO, 3/28/53 – Charles Nichols/Ward Kimball, dir.), was the first of rwo shorts bulled as “Adventures in Music”, and also the studio’s first of two shorts released in 3-D. Whether it was originally anticipated that more shorts be released in this “series” is unknown, but, given the film’s unique visual stule, it is highly likely that any further projects beyond the original two were shelved due to the die-off of audience interest in the medium of 3-D. The film is presented in a distinctly “flat” style of drawing, closely resembling the artistic experiments of UPA, which allowed the animators considerable freedom in adapting the drawings to 3-D, as they could be presented in the manner of slides on different planes of depth from the viewer’s eye, much in the manner Disney had prepared artwork for years when using the multiplane camera, yet without too much worry as to whether characters could be properly rotated in perspectiove. This same manner of presentation was emulated by View Master slides whenever presenting 3-D pictures made from drawn images. At least two later productions (the sequel “Toot, Whisyle, Pkink, and Boom”, to be reviewed in a subsequent chapter of this series, and “Pigs is Pigs”), were presented in the same flattened style, indicating that they too had been possibly initiated with the 3-D format in mind. In fact, as I have previously elaborated in a comment to an article on this website about Disney 3-D, “Pigs is Pigs” is animated with virtually all scenes exhibiting forward or backward motion or multiple layers of animation/background movement, giving every indication that existing prints are the full animation of one eye’s perspective of a completed 3-D project.

Melody (Disney/RKO, 3/28/53 – Charles Nichols/Ward Kimball, dir.), was the first of rwo shorts bulled as “Adventures in Music”, and also the studio’s first of two shorts released in 3-D. Whether it was originally anticipated that more shorts be released in this “series” is unknown, but, given the film’s unique visual stule, it is highly likely that any further projects beyond the original two were shelved due to the die-off of audience interest in the medium of 3-D. The film is presented in a distinctly “flat” style of drawing, closely resembling the artistic experiments of UPA, which allowed the animators considerable freedom in adapting the drawings to 3-D, as they could be presented in the manner of slides on different planes of depth from the viewer’s eye, much in the manner Disney had prepared artwork for years when using the multiplane camera, yet without too much worry as to whether characters could be properly rotated in perspectiove. This same manner of presentation was emulated by View Master slides whenever presenting 3-D pictures made from drawn images. At least two later productions (the sequel “Toot, Whisyle, Pkink, and Boom”, to be reviewed in a subsequent chapter of this series, and “Pigs is Pigs”), were presented in the same flattened style, indicating that they too had been possibly initiated with the 3-D format in mind. In fact, as I have previously elaborated in a comment to an article on this website about Disney 3-D, “Pigs is Pigs” is animated with virtually all scenes exhibiting forward or backward motion or multiple layers of animation/background movement, giving every indication that existing prints are the full animation of one eye’s perspective of a completed 3-D project.

A lengthy medley is entited “Steps of Life to Melody”, continuing to use man as a model, demonstrating songs associated with evolutionary stages from cradle to grave, including “Rock-a-Bye Baby”, “Happy Birthday”, “Far Above Cayuga’s Waters”, the “Wedding March”, and “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers”, among others. Next, the professor discusses musical inspiration, asking the student to artistically illustrate genres of songs. These include, among others, tributes to love songs, sea shanties, western ballads, railroad songs, motherhood, and moon songs. Penelope Pinfeather bemoans that no one ever sings about brains (Take heart, Penelope. During the 50’s a small series of educational children’s 78’s, entitled “Sing a Song of Inventors”, was actually issuesd, proving her wrong.) In conclusion, the professor creates a conductor upon a music chart, and illustrates how a somple melody can be embellished into a symphony, modifying the form of the earlier tune about the bird and the cricket and the willow tree, with striking Ward Kimball impressionistic graphics.

A lengthy medley is entited “Steps of Life to Melody”, continuing to use man as a model, demonstrating songs associated with evolutionary stages from cradle to grave, including “Rock-a-Bye Baby”, “Happy Birthday”, “Far Above Cayuga’s Waters”, the “Wedding March”, and “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers”, among others. Next, the professor discusses musical inspiration, asking the student to artistically illustrate genres of songs. These include, among others, tributes to love songs, sea shanties, western ballads, railroad songs, motherhood, and moon songs. Penelope Pinfeather bemoans that no one ever sings about brains (Take heart, Penelope. During the 50’s a small series of educational children’s 78’s, entitled “Sing a Song of Inventors”, was actually issuesd, proving her wrong.) In conclusion, the professor creates a conductor upon a music chart, and illustrates how a somple melody can be embellished into a symphony, modifying the form of the earlier tune about the bird and the cricket and the willow tree, with striking Ward Kimball impressionistic graphics.

While the film was visually impressive, its 3-D inages were only moderately so as compared to product from other rival studios, including Walter Lantz and Paramount. Additionally, for a film with educational leanings, it really didn’t teach much about the mechanics or composition of music, thus not truly meeting its expected goals, though remaining generally entertaining. Thus, the film did not really make waves from a historical perspective, and for many years lapsed into obscurity. It would take the sequel, Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom, to elevate the presentation to a film equally balancing educational and entertainment goals, raising the product to the level of an Academy Award.

How to Dance (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 7/11/53 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Goofy is a wallflower and social outcast at night clubs because he does not know how to dance (which he covers up for with various excuses like displaying a fake leg cast). Goofy is left alone to pay the checks at the dinner table, while everyone else dances the night away. A narrator (Art Gilmore, for a change) talks Goofy into taking up dance instruction. Goofy first sends for a set of home lessons, including charts with numbered footprint outlines to illustrate the basic steps (which resemble the complexity of an average cartoon football play). Goofy takes this instruction to a real world level by cutting out a series of paper footprint outlines like paper dolls, then spreading them around the room to match the chart. Regrettably, he has left the window open, and a rising breeze begins to scatter the paper patterns helter skelter. Goofy doggedly follows wherever the winds and the traveling footprints lead, planting his final step directly into the rear end of another dog, who socks him in the nose for his troubles.

How to Dance (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 7/11/53 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Goofy is a wallflower and social outcast at night clubs because he does not know how to dance (which he covers up for with various excuses like displaying a fake leg cast). Goofy is left alone to pay the checks at the dinner table, while everyone else dances the night away. A narrator (Art Gilmore, for a change) talks Goofy into taking up dance instruction. Goofy first sends for a set of home lessons, including charts with numbered footprint outlines to illustrate the basic steps (which resemble the complexity of an average cartoon football play). Goofy takes this instruction to a real world level by cutting out a series of paper footprint outlines like paper dolls, then spreading them around the room to match the chart. Regrettably, he has left the window open, and a rising breeze begins to scatter the paper patterns helter skelter. Goofy doggedly follows wherever the winds and the traveling footprints lead, planting his final step directly into the rear end of another dog, who socks him in the nose for his troubles.

Step two has Goofy try dancing with a partner. For this purpose, he borrows from a neighbor an armless dressmaker’s dummy, slipping his own arm through the hole to simulate the hand of his partner to hold. He first attempts to emulate politeness and the social graces, by offering his lady a drink from a punch bowl, pouring the cup down the neck of the headless form. The punch must be spiked, as the dummy begins to stagger. Goofy takes “her” out onto a patio for a breath of fresh night air – but the air isn’t the only thing that’s fresh, as a loud slap is heard offscreen, and Goofy returns with a red face, and his own arm chastising him for attempting to take unfair advantage of a lady! But on with the dance. With one foot on the wheeled base of the dummy, Goofy propels it like a scooter into glides and twirls, ultimately overdoing a spiral and losing his grip on the dummy, which rolls over to a wall while Goofy lands on the floor. The wheeled base lands with one ball bearing inserted into a wall electrical socket. When Goofy inserts his arm again, the results are “shocking”, and the dummy spins him around like a top, then explodes. From the floor, Goofy looks at the camera, and reacts in visibly impressed fashion, “What a gal!”

Home schooling having not completed the process, Goofy attends an accredited dance school. There, with the assistance of various mechanical devices, he learns several international dances: Russian (with mechanical hands lifting his feet high), Irish (performing a jig to avoid bullets being fired at his feet), Highland Fling (his rear end rising and falling with an extendable telescoping seat base), ballet (suspended from a pulley like an actor playing Peter Pan, swung accidentally into the wall), and Mexican Hat Dance (with his feet manipulated by marionette strings). A final ballroom dance with a lady in long gown reveals how a lady maintains her flowing gliding poise – as she passes in front of a backlit window, her silhouette shown seated and riding upon a wheeled stool). “Graduation” is performed by kicking Goofy out the door, and he proceeds confidently to the night club. He asks a young lady onto the floor, and checks a series of crib notes illustrating his basic dance steps which he has inked onto the rotating cuff of his suit. He has, however, picked the wrong night to visit the club, as a quite different-than-usual act has been booked for the evening’s entertainment – the studio’s own animator band, The Firehouse Five Plus Two. As the entertainers launch into one of their raucous Dixieland arrangements, Goofy finds activity on the dance floor converted inti a stomp – with himself the one being stomped on. Elbows wave back and forth, jabbing and pounding at Goofys face and ribs. A full shot of the dance floor shows the Goof bouncing into the air, then back among the violent crowd, briefly rising again in the pose of a drowning man going down for the third time, and sinking beneath the wave of humanity at the film’s iris out.

Home schooling having not completed the process, Goofy attends an accredited dance school. There, with the assistance of various mechanical devices, he learns several international dances: Russian (with mechanical hands lifting his feet high), Irish (performing a jig to avoid bullets being fired at his feet), Highland Fling (his rear end rising and falling with an extendable telescoping seat base), ballet (suspended from a pulley like an actor playing Peter Pan, swung accidentally into the wall), and Mexican Hat Dance (with his feet manipulated by marionette strings). A final ballroom dance with a lady in long gown reveals how a lady maintains her flowing gliding poise – as she passes in front of a backlit window, her silhouette shown seated and riding upon a wheeled stool). “Graduation” is performed by kicking Goofy out the door, and he proceeds confidently to the night club. He asks a young lady onto the floor, and checks a series of crib notes illustrating his basic dance steps which he has inked onto the rotating cuff of his suit. He has, however, picked the wrong night to visit the club, as a quite different-than-usual act has been booked for the evening’s entertainment – the studio’s own animator band, The Firehouse Five Plus Two. As the entertainers launch into one of their raucous Dixieland arrangements, Goofy finds activity on the dance floor converted inti a stomp – with himself the one being stomped on. Elbows wave back and forth, jabbing and pounding at Goofys face and ribs. A full shot of the dance floor shows the Goof bouncing into the air, then back among the violent crowd, briefly rising again in the pose of a drowning man going down for the third time, and sinking beneath the wave of humanity at the film’s iris out.

Ballet-Oop (UPA/Columbia, 2/11/54 – Robert Cannon, dir.) – A strange little film, seeming to be aimed at a limited target market – those parents and students familiar with the chore of sending little girls to ballet class. It almost borders on the instructional rather than scoring as a general entertainment, its humor being on the exceptionally light side, with most footage devoted to a run through of the principal steps of ballet, and an extended recital with little presence of comedy content. The title is perhaps funnier than the picture itself, and unfortunately leaves the audience expecting more than what the film can deliver (Ah, where is Quincy Magoo when you need him?). If one forgets it, and views the film as purely instructional, it is pleasant enough to get by.

Ballet-Oop (UPA/Columbia, 2/11/54 – Robert Cannon, dir.) – A strange little film, seeming to be aimed at a limited target market – those parents and students familiar with the chore of sending little girls to ballet class. It almost borders on the instructional rather than scoring as a general entertainment, its humor being on the exceptionally light side, with most footage devoted to a run through of the principal steps of ballet, and an extended recital with little presence of comedy content. The title is perhaps funnier than the picture itself, and unfortunately leaves the audience expecting more than what the film can deliver (Ah, where is Quincy Magoo when you need him?). If one forgets it, and views the film as purely instructional, it is pleasant enough to get by.

A ballet instructor (Miss Placement), offers beginning rules on posture to a starting class of four students, at the Hot-Foot School of Ballet. Her lesson is interrupted by Mr. Hot-Foot, the owner, who announces the big news that, to draw publicity for the little school, he has entered the class in the local ballet festival, just three weeks away. This, after Miss Placement has just instructed the kids that becoming a ballet dancer takes years of hard work. But Hot-Foot insists the kids will take top honors, and that then, they will be able to pay the rent and turn the heat on again. Hot-Foot wanders off in a dither, searching for a lost hat, ignoring Miss Placement’s moans that the feat can’t be done. “But I need the money”, she groans, realizing she’ll have to do the best she can. Thus begins a lengthy series of illustrated instructions of steps and leaps, with only minimal time for smiles from visual suggestions of awkwardness. The appointed day arrives to find teacher and students lying exhausted on the floor, while Hot-Foot, still in search of his hat, calls on them to get ready for the performance. A juvenile recital piece. “The Apple Blosson and the Grasshopper”, is presented at the Glendale Ballet Festival. (Was Glendale the home of the studio?) It’s pretty straightforward, meaningless fluff about a bee and butterfly competing romantically for the affections of an apple blossom, which is ultimately eaten by a grasshopper, leaving the suitors sad and lonely, until two more blossoms sprout, giving them both a partner. (This means I count five students, thus having to conclude that the one playing the grasshopper must be doing a quick costume change.) What is a bit embarrassing about the film’s presentation is that Marvin Miller is drawn in to act as narrator of the storyline of the ballet, but not from a podium on the stage, instead as a loquacious member of the audience who just won’t shut up during the middle of the performance – which all seems quite unnatural and intrusive. The final scenes of the film have Hot-Foot congratulating the teacher and class on winning renown for the school, but showing the aftermath of their work – 1,400 new enrollees lined up outside the school door. And Hot-Foot has signed them all up for competition in a national ballet festival in two weeks. Miss Placement responds that Hot-Foot will also be happy to know that she found his hat – which she pulls down over Hot-Foot’s face, leaving him to stumble around blindly as he continues to mumble about opening a whole chain of ballet schools, entering the door to a stairway, and tumbling down into the building’s basement for the film’s ending.

A ballet instructor (Miss Placement), offers beginning rules on posture to a starting class of four students, at the Hot-Foot School of Ballet. Her lesson is interrupted by Mr. Hot-Foot, the owner, who announces the big news that, to draw publicity for the little school, he has entered the class in the local ballet festival, just three weeks away. This, after Miss Placement has just instructed the kids that becoming a ballet dancer takes years of hard work. But Hot-Foot insists the kids will take top honors, and that then, they will be able to pay the rent and turn the heat on again. Hot-Foot wanders off in a dither, searching for a lost hat, ignoring Miss Placement’s moans that the feat can’t be done. “But I need the money”, she groans, realizing she’ll have to do the best she can. Thus begins a lengthy series of illustrated instructions of steps and leaps, with only minimal time for smiles from visual suggestions of awkwardness. The appointed day arrives to find teacher and students lying exhausted on the floor, while Hot-Foot, still in search of his hat, calls on them to get ready for the performance. A juvenile recital piece. “The Apple Blosson and the Grasshopper”, is presented at the Glendale Ballet Festival. (Was Glendale the home of the studio?) It’s pretty straightforward, meaningless fluff about a bee and butterfly competing romantically for the affections of an apple blossom, which is ultimately eaten by a grasshopper, leaving the suitors sad and lonely, until two more blossoms sprout, giving them both a partner. (This means I count five students, thus having to conclude that the one playing the grasshopper must be doing a quick costume change.) What is a bit embarrassing about the film’s presentation is that Marvin Miller is drawn in to act as narrator of the storyline of the ballet, but not from a podium on the stage, instead as a loquacious member of the audience who just won’t shut up during the middle of the performance – which all seems quite unnatural and intrusive. The final scenes of the film have Hot-Foot congratulating the teacher and class on winning renown for the school, but showing the aftermath of their work – 1,400 new enrollees lined up outside the school door. And Hot-Foot has signed them all up for competition in a national ballet festival in two weeks. Miss Placement responds that Hot-Foot will also be happy to know that she found his hat – which she pulls down over Hot-Foot’s face, leaving him to stumble around blindly as he continues to mumble about opening a whole chain of ballet schools, entering the door to a stairway, and tumbling down into the building’s basement for the film’s ending.

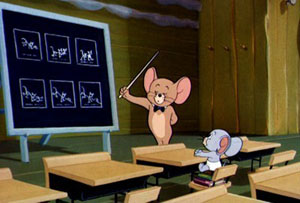

Little School Mouse (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 5/29/54 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Jerry Mouse enjoyed so much barging in on Tom’s lessons in Professor Tom, that this episode finds the roles reversed, with Jerry now the possessor of a certificate qualifying him as a professor in the art of outwitting cats, in charge of his own class of one – little Tuffy (or Nibbles, if you prefer). Tuffy sits patiently at his desk, in an empty mousehole classroom, glancing up at a pocket watch serving as a clock on the wall, reading ten minutes after nine o’clock. The silence is broken by the sounds of a furious chase outside, explaining the professor’s tardiness, as Jerry races into the mousehole with Tom right on his heels, slamming the door in Tom’s face. Jerry wears a small collar anf black bow tie to denote his official instructor status (at least the tie serves a purpose as a plot point, rather than the way it would be used for arbitrary all-purpose reasons in Hanna-Barbera’s television “Tom and Jerry Show”, as a budget cutter to allow Jerry to be drawn in head-only cels with stationary body by adding a line across his neck). Jerry straightens the alignment of his diploma frame and the papers on his desk, all of which have been upset by his hasty entrance, and assumes a dignified demeanor to begin class. Using blackboard illustrations and a pointer as did Tom, Jerry points to lesson one – what usually happens to mice in their encounters with felines. “Cat chases mouse; Cat catches mouse; Cat eats mouse.” (Illustration of step three is funny, as the cat, drawn as a stick figure with a line for an abdomen, now has a bulge in his abdomen line in the shape of the devoured mouse. Tuffy doesn’t like this lesson, and starts to cry. But Jerry moves on to lesson two – the way things should be. “Cat chases mouse; Mouse runs into hole; Cat says bad words.” Tuffy reacts with opposite emotion, breaking into laughter.

Little School Mouse (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 5/29/54 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Jerry Mouse enjoyed so much barging in on Tom’s lessons in Professor Tom, that this episode finds the roles reversed, with Jerry now the possessor of a certificate qualifying him as a professor in the art of outwitting cats, in charge of his own class of one – little Tuffy (or Nibbles, if you prefer). Tuffy sits patiently at his desk, in an empty mousehole classroom, glancing up at a pocket watch serving as a clock on the wall, reading ten minutes after nine o’clock. The silence is broken by the sounds of a furious chase outside, explaining the professor’s tardiness, as Jerry races into the mousehole with Tom right on his heels, slamming the door in Tom’s face. Jerry wears a small collar anf black bow tie to denote his official instructor status (at least the tie serves a purpose as a plot point, rather than the way it would be used for arbitrary all-purpose reasons in Hanna-Barbera’s television “Tom and Jerry Show”, as a budget cutter to allow Jerry to be drawn in head-only cels with stationary body by adding a line across his neck). Jerry straightens the alignment of his diploma frame and the papers on his desk, all of which have been upset by his hasty entrance, and assumes a dignified demeanor to begin class. Using blackboard illustrations and a pointer as did Tom, Jerry points to lesson one – what usually happens to mice in their encounters with felines. “Cat chases mouse; Cat catches mouse; Cat eats mouse.” (Illustration of step three is funny, as the cat, drawn as a stick figure with a line for an abdomen, now has a bulge in his abdomen line in the shape of the devoured mouse. Tuffy doesn’t like this lesson, and starts to cry. But Jerry moves on to lesson two – the way things should be. “Cat chases mouse; Mouse runs into hole; Cat says bad words.” Tuffy reacts with opposite emotion, breaking into laughter.

Instruction moves into learning by doing. Jerry takes Tuffy to a stage-style backdrop with a mousehole opening, and a mechanical cranked device simulating a cat’s paw, poised over the mousehole entrance. Jerry peers out from the hole, looking around carefully, looks up to spy the paw, and runs back into the hole. He instructs Tuffy to do the same, while Jerry moves to the crank of the paw device. Tuffy peers out, then advances forward as if the coast is clear. Jerry cranks the mechanism, and brings the paw down squarely on Tuffy’s tail. Having failed this first test, Tuffy is instructed to switch places with Jerry at the crank, so that Jerry can demonstrate the proper way again. Jerry again peers out, but does not count on the swift reflexes of Tuffy, who turns the crank and whomps Jerry soundly with the paw. The paw is raised, and Jerry tries to scamper out of harm’s way, but Tuffy brings the paw down upon him again – and again – and again, and again, and again. We see Tuffy continuing to turn the crank with all hs might, his eyes closed in concentration – then Tuffy stops, opening his eyes to find out what became of the professor. Seeing no one, he walks over to the paw and lifts it to look underneath – finding a well-flattened Jerry prone under it. Tuffy drops the paw, races over to the teacher’s desk to place a sign upon it reading “Class Dismissed”, and beats a retreat for the mousehole door. But Jerry, returned to his original shape, grabs the student by the diaper to prevent his exit. Tuffy sheepishly slips to the corner stool of the classroom, and places the dunce cap upon his head.

Instruction moves into learning by doing. Jerry takes Tuffy to a stage-style backdrop with a mousehole opening, and a mechanical cranked device simulating a cat’s paw, poised over the mousehole entrance. Jerry peers out from the hole, looking around carefully, looks up to spy the paw, and runs back into the hole. He instructs Tuffy to do the same, while Jerry moves to the crank of the paw device. Tuffy peers out, then advances forward as if the coast is clear. Jerry cranks the mechanism, and brings the paw down squarely on Tuffy’s tail. Having failed this first test, Tuffy is instructed to switch places with Jerry at the crank, so that Jerry can demonstrate the proper way again. Jerry again peers out, but does not count on the swift reflexes of Tuffy, who turns the crank and whomps Jerry soundly with the paw. The paw is raised, and Jerry tries to scamper out of harm’s way, but Tuffy brings the paw down upon him again – and again – and again, and again, and again. We see Tuffy continuing to turn the crank with all hs might, his eyes closed in concentration – then Tuffy stops, opening his eyes to find out what became of the professor. Seeing no one, he walks over to the paw and lifts it to look underneath – finding a well-flattened Jerry prone under it. Tuffy drops the paw, races over to the teacher’s desk to place a sign upon it reading “Class Dismissed”, and beats a retreat for the mousehole door. But Jerry, returned to his original shape, grabs the student by the diaper to prevent his exit. Tuffy sheepishly slips to the corner stool of the classroom, and places the dunce cap upon his head.

Next lesson: a field trip into the living room, to address Assignment 1 – “Remove cat’s whiskers without waking cat.” Jerry demonstrates his stealthful approach, slipping behind various objects of furniture and Tom’s bowl while Tom sleeps, then slipping under the rug to neatly yank a whisker off Tom’s face without rousing him. Jerry points Tuffy in Tom’s direction to accomplish the same task, and waits alongside a wall as the young student attempts to accomplish his mission. Tuffy returns with a whisker in hand – but it is still firmly attached to Tom’s face! Jerry grabs Tuffy and drags him toward the mousehole – but Tuffy still clings to the whisker, dragging Tom along too. Jerry pauses to complete the whisker pluck and hopefully lose Tom, but Tuffy races ahead to the mousehole, thoughtlessly slamming the door behind him, and leaving poor Jerry out in the cold. From viewpoint inside the mousehole, we hear the sounds of a fierce struggle outside, then quiet. Tuffy opens the door, revealing Jerry, dizzily swaying, with one black eye and his instruction book smashed over his head, then collapsing through the open doorway onto the floor.

Lesson two: “Get cheese from cupboard without waking cat.” Jerry again shows proper technique, using the pull strings of Venetian blinds to raise himself to the kitchen counter like a scaffold, and sailing across the kitchen sink in a cup and saucer to the cheese. He grabs a morsel, then slides down a mop handle for a hasty exit. Things almost go awry as the cheese is jostled from his hand when he hits to mop head, and bounces off Tom’s brow. Jerry leaps upon Tom’s eyelids, holding them shut, and pets Tom’s head until he relaxes and falls back to sleep. Jerry carries the morsel back to the mousehole, showing it to Tuffy, then swallows it as his reward. Now it is Tuffy’s turn. Ignoring the lesson’s instruction “without waking cat”, Tuffy prefers a direct approach. He walks up to Tom, gently nudging the sleepy cat to open his eyes, and politely points to the cheese on the kitchen counter. Still only half awake, Tom reaches up, hands the cheese wedge to Tuffy, then goes back to sleep again. Tuffy returns, swallowing the cheese wedge which is three times his own size, leaving a visible bulge in his torso.

Lesson two: “Get cheese from cupboard without waking cat.” Jerry again shows proper technique, using the pull strings of Venetian blinds to raise himself to the kitchen counter like a scaffold, and sailing across the kitchen sink in a cup and saucer to the cheese. He grabs a morsel, then slides down a mop handle for a hasty exit. Things almost go awry as the cheese is jostled from his hand when he hits to mop head, and bounces off Tom’s brow. Jerry leaps upon Tom’s eyelids, holding them shut, and pets Tom’s head until he relaxes and falls back to sleep. Jerry carries the morsel back to the mousehole, showing it to Tuffy, then swallows it as his reward. Now it is Tuffy’s turn. Ignoring the lesson’s instruction “without waking cat”, Tuffy prefers a direct approach. He walks up to Tom, gently nudging the sleepy cat to open his eyes, and politely points to the cheese on the kitchen counter. Still only half awake, Tom reaches up, hands the cheese wedge to Tuffy, then goes back to sleep again. Tuffy returns, swallowing the cheese wedge which is three times his own size, leaving a visible bulge in his torso.

Final lesson: tie a bell around the cat’s neck. Jerry again provides demonstration, but this time Tom is not sound asleep, but peers at him periodically with one eye to keep track of his movements. Jerry slips a string under Tom’s chin, not observing that Tom has raised his head to allow the string to neatly pass under it. Jerry then climbs on Tom’s back, attempting to secure a knot to tie on the bell. Without even opening his eyelids, wide-awake Tom offers an assist by placing his finger on the center of the knot so that Jerry can secure it. As the string is tied off, Jerry becomes aware that this was all too easy, and something is amiss. He runs for his life, but Tom snatches him up in one paw. From viewpoint in the mousehole again, another voilent battle is heard offscreen – and Jerry enters, hogtied in string from neck to tail, mission failed. Tuffy, who has been given a bell of his own for the test, peers out at Tom and swallows hard in fearful anticipation, but exits the hole carrying a small gift-wrapped package. Tom, still awake, stares down sternly at the mouse, wondering what to expect next. Tuffy places the package in front of Tom, and gestures that this is for him. Tom unwraps the package, revealing Tuffy’s bell. But, being presented with it as a gift, Tom is overjoyed, and happily ties on the bell himself! Jerry slaps his hand to his own forehead at being entirely shown up in this embarrassing manner, then walks over to his teaching certificate, removes it from the wall, and tosses it into the trash in the alley. The final shot shows yet another role reversal, with Tuffy now instructing at the blackboard, while Jerry wears the dunce cap. Tuffy points to his own chalk illustration, captioned “Cats and mice should be friends.” (The same lesson Jerry was trying to teach in “Professor Tom”.) Jerry shakes his head in a stubborn no, but the camera pulls back to reveal a new student in the desk next to him – Tom, who counters with an eager nod of yes, gives Jerry a kiss, and happily rings the bell around his neck for the iris out.

Final lesson: tie a bell around the cat’s neck. Jerry again provides demonstration, but this time Tom is not sound asleep, but peers at him periodically with one eye to keep track of his movements. Jerry slips a string under Tom’s chin, not observing that Tom has raised his head to allow the string to neatly pass under it. Jerry then climbs on Tom’s back, attempting to secure a knot to tie on the bell. Without even opening his eyelids, wide-awake Tom offers an assist by placing his finger on the center of the knot so that Jerry can secure it. As the string is tied off, Jerry becomes aware that this was all too easy, and something is amiss. He runs for his life, but Tom snatches him up in one paw. From viewpoint in the mousehole again, another voilent battle is heard offscreen – and Jerry enters, hogtied in string from neck to tail, mission failed. Tuffy, who has been given a bell of his own for the test, peers out at Tom and swallows hard in fearful anticipation, but exits the hole carrying a small gift-wrapped package. Tom, still awake, stares down sternly at the mouse, wondering what to expect next. Tuffy places the package in front of Tom, and gestures that this is for him. Tom unwraps the package, revealing Tuffy’s bell. But, being presented with it as a gift, Tom is overjoyed, and happily ties on the bell himself! Jerry slaps his hand to his own forehead at being entirely shown up in this embarrassing manner, then walks over to his teaching certificate, removes it from the wall, and tosses it into the trash in the alley. The final shot shows yet another role reversal, with Tuffy now instructing at the blackboard, while Jerry wears the dunce cap. Tuffy points to his own chalk illustration, captioned “Cats and mice should be friends.” (The same lesson Jerry was trying to teach in “Professor Tom”.) Jerry shakes his head in a stubborn no, but the camera pulls back to reveal a new student in the desk next to him – Tom, who counters with an eager nod of yes, gives Jerry a kiss, and happily rings the bell around his neck for the iris out.

Yankee Doodle Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/28/54 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This film presents an example of where Warners was going artistically with the new trends of limited animation popularized by UPA. While characters would remain fully animated for most productions, the days of detailed scenic backgrounds were waning, in favor of minimal use of a few basic solid colors for background art, with many props and details only suggested by ink outlining, often not even matching the borders of the colors painted in their proximity. Friz Freleng would be a champion of this movement, often far exceeding the simplicity of artwork produced for companion Chuck Jones productions, and would eventually bring this style to a head in his own independent productiond for the Pink Panther series, reducing many backgrounds to single solid colors and letting the character animation alone move the story.

Yankee Doodle Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/28/54 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This film presents an example of where Warners was going artistically with the new trends of limited animation popularized by UPA. While characters would remain fully animated for most productions, the days of detailed scenic backgrounds were waning, in favor of minimal use of a few basic solid colors for background art, with many props and details only suggested by ink outlining, often not even matching the borders of the colors painted in their proximity. Friz Freleng would be a champion of this movement, often far exceeding the simplicity of artwork produced for companion Chuck Jones productions, and would eventually bring this style to a head in his own independent productiond for the Pink Panther series, reducing many backgrounds to single solid colors and letting the character animation alone move the story.

Bugs’ nephew Clyde is hitting the books, trying to remember names and dates for a test on Revolutionary War history that day. Bugs volunteers to help. “Do you know American histoty?”, asks Clyde. “Why, we rabbits have made American history”, states Bugs proudly. Clyde eagerly seats himself to listen to Bugs spin his accounts of the past. Beginning with the purchase of Manhattan, Bugs compares the island of the past to the island of today, as a visual of the skyline dissolves to a high-rise line of teepees, and a passing ocean liner is replaced with a long Indian canoe. “And the Statue of Liberty was just a little girl at the time”, as the statute dissolves to a version aged about three years old. The island is bought for a song, literally, as the purchaser hands the chief a page of sheet music, (Can anyone identify the tune depicted?) A gag which passes by quickly has the For Sale sign for the island advertising, “Beautiful view of Brooklyn on a clear day.” The scene changes to Philadelphia, where Bugs’s ancestor encounters Benjamin Franklin flying his kite, and volunteers to mind it while Ben turms out the latest edition of Ye Saturday Evening Post. Lightning strikes, and Bugs finds himself “all lit up”. “I’ve discovered electricity!” cheers Franklin, carrying the blinking bunny home. “He discovered electricity”, Bugs repeats sarcastically, as the scene blacks out.

Bugs’ nephew Clyde is hitting the books, trying to remember names and dates for a test on Revolutionary War history that day. Bugs volunteers to help. “Do you know American histoty?”, asks Clyde. “Why, we rabbits have made American history”, states Bugs proudly. Clyde eagerly seats himself to listen to Bugs spin his accounts of the past. Beginning with the purchase of Manhattan, Bugs compares the island of the past to the island of today, as a visual of the skyline dissolves to a high-rise line of teepees, and a passing ocean liner is replaced with a long Indian canoe. “And the Statue of Liberty was just a little girl at the time”, as the statute dissolves to a version aged about three years old. The island is bought for a song, literally, as the purchaser hands the chief a page of sheet music, (Can anyone identify the tune depicted?) A gag which passes by quickly has the For Sale sign for the island advertising, “Beautiful view of Brooklyn on a clear day.” The scene changes to Philadelphia, where Bugs’s ancestor encounters Benjamin Franklin flying his kite, and volunteers to mind it while Ben turms out the latest edition of Ye Saturday Evening Post. Lightning strikes, and Bugs finds himself “all lit up”. “I’ve discovered electricity!” cheers Franklin, carrying the blinking bunny home. “He discovered electricity”, Bugs repeats sarcastically, as the scene blacks out.

The revolution begins from a surprise visit of the King to the Boston tea warehouses, where he orders boxes of carpet tacks to be spread over the colonists’ tea, declaring, “They’re tea tacks now!” Continuing to confuse “tacks” with “Tax”, Bugs describes the colonists’ rounding up of an army to resust drinking their tea with tacks. In the manner of a WWII draft, conscription numbers are drawn at random from a fish bowl. George Washington is one of the first to receive his induction notice, and tells wife Martha to run the candy stores alone while he is off to fight the war (Reference to a popular East Coast candy store chain). Now with an army, they need a flag. Various proposed designs from the period are shown, plus one that never got on the drawing boards, consistung of a tic tac toe game on a bare white sheet. At Betsy Ross’s house, Bugs appears again (taking care when entering the grounds near the front gate, where a sign cautions, “George Washington Slipped Here” (pun on the common phrase and title of a prior Warner Brothers feature, “George Washington Slept Here”.) Betsy (played by Granny), shows Bugs her needle handiwork – a completed flag, except for the corner, wich is still in solid blue with no decoration. Bugs insists that blue field needs something, and paces back in forth in the front yard, hoping to be hit by an inspiration. He hets his wish, by stepping upon the tines of a rake, which pops upward and smacks Bugs in the face with its handle. A circle of stars spins around Bugs’ dizzy head. In a moment of genius, Bugs points to them, and says, “Hey, Betsy, does this give you an idea?” And history is again made.

The revolution begins from a surprise visit of the King to the Boston tea warehouses, where he orders boxes of carpet tacks to be spread over the colonists’ tea, declaring, “They’re tea tacks now!” Continuing to confuse “tacks” with “Tax”, Bugs describes the colonists’ rounding up of an army to resust drinking their tea with tacks. In the manner of a WWII draft, conscription numbers are drawn at random from a fish bowl. George Washington is one of the first to receive his induction notice, and tells wife Martha to run the candy stores alone while he is off to fight the war (Reference to a popular East Coast candy store chain). Now with an army, they need a flag. Various proposed designs from the period are shown, plus one that never got on the drawing boards, consistung of a tic tac toe game on a bare white sheet. At Betsy Ross’s house, Bugs appears again (taking care when entering the grounds near the front gate, where a sign cautions, “George Washington Slipped Here” (pun on the common phrase and title of a prior Warner Brothers feature, “George Washington Slept Here”.) Betsy (played by Granny), shows Bugs her needle handiwork – a completed flag, except for the corner, wich is still in solid blue with no decoration. Bugs insists that blue field needs something, and paces back in forth in the front yard, hoping to be hit by an inspiration. He hets his wish, by stepping upon the tines of a rake, which pops upward and smacks Bugs in the face with its handle. A circle of stars spins around Bugs’ dizzy head. In a moment of genius, Bugs points to them, and says, “Hey, Betsy, does this give you an idea?” And history is again made.

“Does THIS answer your question?”

Spare the Rod (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 9/8/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), must rank among the most mature of short subjects in the series’ history – as it is doubtful any mother would have wanted it to be seen by an impressionable young child of grade school or pre-school age withot some explanation, for the possibility of giving the child too many bad ideas by example. Ahead of its time, the film deals with the rise of juvenile delinquency among students, to a more realistic degree than the exotic weaponry displayed in Goofy’s “Teachers are People”. The topic would within a year receive more widespread national prominence, through the publication of a novel, and within a short time thereafter, release of a feature film, entitled “Blackboard Jungle.” For many years., I had assumed this film to be a parody of such work, never realizing until now that it was instead predicting things to come.

Spare the Rod (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 9/8/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), must rank among the most mature of short subjects in the series’ history – as it is doubtful any mother would have wanted it to be seen by an impressionable young child of grade school or pre-school age withot some explanation, for the possibility of giving the child too many bad ideas by example. Ahead of its time, the film deals with the rise of juvenile delinquency among students, to a more realistic degree than the exotic weaponry displayed in Goofy’s “Teachers are People”. The topic would within a year receive more widespread national prominence, through the publication of a novel, and within a short time thereafter, release of a feature film, entitled “Blackboard Jungle.” For many years., I had assumed this film to be a parody of such work, never realizing until now that it was instead predicting things to come.

A narrator describes this as the story of a town that had to take a stand, as its juveniles were getting badly our of hand. They congregated at pool halls and places respectable mice wouldn’t go, to smoke, gamble and fight – and other things one wouldn’t care to know. The opening sequence shows them causing a riot in the pool hall, breaking up everything in sight. The owner tries to chase them out, but as he yells “Stop!”, his mouth is filled with a barrage of billiard balls. He is smacked by a pool cue atop one of the tables, where another mouse molds him into a triangle with a pool rack, while a third shoots the cue ball at him, breaking him into 15 colored spheres which disappear down the pockets of the table, and reassemble as himself from out of the ball chute.

A narrator describes this as the story of a town that had to take a stand, as its juveniles were getting badly our of hand. They congregated at pool halls and places respectable mice wouldn’t go, to smoke, gamble and fight – and other things one wouldn’t care to know. The opening sequence shows them causing a riot in the pool hall, breaking up everything in sight. The owner tries to chase them out, but as he yells “Stop!”, his mouth is filled with a barrage of billiard balls. He is smacked by a pool cue atop one of the tables, where another mouse molds him into a triangle with a pool rack, while a third shoots the cue ball at him, breaking him into 15 colored spheres which disappear down the pockets of the table, and reassemble as himself from out of the ball chute.

The scene moves to the classroom, where the students are also entirely uncontrollable. Students smoke at their desks, read the comics, and pelt each other with slingshot and peashooter fire. A professor enters with a cheery, “Good morning, children”, only to be battered by a steam of flying textbooks, pencils, eggs, ink bottles, tomatoes, and even an alarm clock. The teacher attempts to crawl away toward the door, but a student grabs his coattail, tying it to the pull ting of a hanging chart, which rolls up like as windowshade, trapping the professor inside. One student has made chalk drawings of nine teachers in a grid on the blackboard, one of whom already has an X drawn through his image, and adds a second X through the picture of the professor we have just seen. A heavy-set, gruff-looking female teacher enters the doorway. “Bring ‘em on”, jeers one of the students. She calls for the class to come to order, but a mouse lounging on her desk while eating lunch replies, “Go on home, ya old battle-axe.” Taking a pepper shaker, the mouse shakes out its whole contents into the path of an electric fan, blowing the contents right into the teacher’s nose. She inhales and delivers a powerful sneeze, so forceful that she is blasted through the wall of the schoolroom and out of the building. The mouse at the blackboard crosses a X through her picture, completing a tic tac toe row on the grid.

The scene moves to the classroom, where the students are also entirely uncontrollable. Students smoke at their desks, read the comics, and pelt each other with slingshot and peashooter fire. A professor enters with a cheery, “Good morning, children”, only to be battered by a steam of flying textbooks, pencils, eggs, ink bottles, tomatoes, and even an alarm clock. The teacher attempts to crawl away toward the door, but a student grabs his coattail, tying it to the pull ting of a hanging chart, which rolls up like as windowshade, trapping the professor inside. One student has made chalk drawings of nine teachers in a grid on the blackboard, one of whom already has an X drawn through his image, and adds a second X through the picture of the professor we have just seen. A heavy-set, gruff-looking female teacher enters the doorway. “Bring ‘em on”, jeers one of the students. She calls for the class to come to order, but a mouse lounging on her desk while eating lunch replies, “Go on home, ya old battle-axe.” Taking a pepper shaker, the mouse shakes out its whole contents into the path of an electric fan, blowing the contents right into the teacher’s nose. She inhales and delivers a powerful sneeze, so forceful that she is blasted through the wall of the schoolroom and out of the building. The mouse at the blackboard crosses a X through her picture, completing a tic tac toe row on the grid.

The scene changes to a public meeting hall, where P.T.A. members, the Lions’ Club, Rotary Club, Kiwanis Club, Citizen’s League, and other concerned parents and citizens (including delegations with signs reading “Pelham”, “Eastchester, N.Y.”, and “New Rochelle” (the home of the Terrytoons studio)) congregate, demanding action. A consensus is reached that they need a leader, brave and strong, to show these kids right from wrong – one who’s got the stuff to handle kids so tough. Who else but Mighty Mouse? And so, Mighty resorts to unusual incognito tactics, infiltrating the delinquent’s territory, disguised as a boy scout, in hopes of winning their respect. Their first reaction is the polar opposite. “Let’s give him da works”, they conspire. Their toughest member comes forward, a chip of wood placed on his shoulder. “Go on, knock it off”, the bully challenges. Mighty obliges, but in an unexpected way – removing the bully from under the piece of wood, with a mere flick of his finger. The shocked tough guy rises from the pavement, and lands a right directly on Mighty’s jaw. Mighty does not move, and the blow results in a large metallic clang, as the bully’s hand swells up in red, and exits the frame repeatedly yelling “OW!” In pain. Pairs of other mice approach with wooden clubs, but Mighty ducks each of the clibs’ swings, letting the mice’s blows fall upon each other. The fallen mice converge upon Mighty in a fight cloud, but as the dust clears. Mighty, still looking untouched, is last man standing. Only a pair of mice dropping a heavy iron stove from a second story window above brings Mighty to a momentary incapacitation, trapping him between steel and pavement. A police whistle is heard, and one mouse calls out, “Cheese it! The cops”. The mice hurriedly hijack a moving van, with one climbing into the cab and the others into the cargo compartment, and the vehicle takes off at high speed for a getaway.

The scene changes to a public meeting hall, where P.T.A. members, the Lions’ Club, Rotary Club, Kiwanis Club, Citizen’s League, and other concerned parents and citizens (including delegations with signs reading “Pelham”, “Eastchester, N.Y.”, and “New Rochelle” (the home of the Terrytoons studio)) congregate, demanding action. A consensus is reached that they need a leader, brave and strong, to show these kids right from wrong – one who’s got the stuff to handle kids so tough. Who else but Mighty Mouse? And so, Mighty resorts to unusual incognito tactics, infiltrating the delinquent’s territory, disguised as a boy scout, in hopes of winning their respect. Their first reaction is the polar opposite. “Let’s give him da works”, they conspire. Their toughest member comes forward, a chip of wood placed on his shoulder. “Go on, knock it off”, the bully challenges. Mighty obliges, but in an unexpected way – removing the bully from under the piece of wood, with a mere flick of his finger. The shocked tough guy rises from the pavement, and lands a right directly on Mighty’s jaw. Mighty does not move, and the blow results in a large metallic clang, as the bully’s hand swells up in red, and exits the frame repeatedly yelling “OW!” In pain. Pairs of other mice approach with wooden clubs, but Mighty ducks each of the clibs’ swings, letting the mice’s blows fall upon each other. The fallen mice converge upon Mighty in a fight cloud, but as the dust clears. Mighty, still looking untouched, is last man standing. Only a pair of mice dropping a heavy iron stove from a second story window above brings Mighty to a momentary incapacitation, trapping him between steel and pavement. A police whistle is heard, and one mouse calls out, “Cheese it! The cops”. The mice hurriedly hijack a moving van, with one climbing into the cab and the others into the cargo compartment, and the vehicle takes off at high speed for a getaway.

Only one problem – the mouse in front has never driven a truck before, and the vehicle careens out of control. To make things doubly perilois, one mouse is tossed out of the rear as the truck bounces over the tracks at a railroad crossing. His foot lands in the worst of places – wedged between the track rail and wooden slats providing the road bed for the auto crossing, so he is unable to move – while an approaching train is heard in the distance. Now Mighty, who finally frees himself from the stove, little realizes that he is going to have to save the day twice. Removing his scout disguise, Mighty soars into the skies, first spotting the runaway van. The vehicle is on a collision course with a telephone pole. Mighty zooms from the sky, and snaps off the pole just inches before the van can hit it, as the truck passes over the corner and continues down the road. Mighty flies under the moving chassus and grabs hold of the rear axle/transmission. Pulling backwards does not stop the vegicle due to its onrushing speed, but instead severs the body frame of the truck from the chassis. Nevertheless, luck is with Mighty, as the chassis makes contact with the road, and, despite a bumpy ride, grinds gradually to a halt, with no one hurt. But there’s still the matter of the kid left behind at the railroad tracks. The poor mouse is on his knees saying his prayers, with the train whistle looming ever closer in the distance. Mighty flies back along the road at full speed, then spots the cross-track of the train. Soaring to the train’s position, Mighty first reaches the caboose end, and desperately tries to stop the train by pulling backwards on the caboose’s bumper. He only succeeds in uncoupling the car, while the engine and remaining cars advance at full steam. Mighty now finds himself in a race with the careening train, inching forward car length by car length to reach the engine.

Only one problem – the mouse in front has never driven a truck before, and the vehicle careens out of control. To make things doubly perilois, one mouse is tossed out of the rear as the truck bounces over the tracks at a railroad crossing. His foot lands in the worst of places – wedged between the track rail and wooden slats providing the road bed for the auto crossing, so he is unable to move – while an approaching train is heard in the distance. Now Mighty, who finally frees himself from the stove, little realizes that he is going to have to save the day twice. Removing his scout disguise, Mighty soars into the skies, first spotting the runaway van. The vehicle is on a collision course with a telephone pole. Mighty zooms from the sky, and snaps off the pole just inches before the van can hit it, as the truck passes over the corner and continues down the road. Mighty flies under the moving chassus and grabs hold of the rear axle/transmission. Pulling backwards does not stop the vegicle due to its onrushing speed, but instead severs the body frame of the truck from the chassis. Nevertheless, luck is with Mighty, as the chassis makes contact with the road, and, despite a bumpy ride, grinds gradually to a halt, with no one hurt. But there’s still the matter of the kid left behind at the railroad tracks. The poor mouse is on his knees saying his prayers, with the train whistle looming ever closer in the distance. Mighty flies back along the road at full speed, then spots the cross-track of the train. Soaring to the train’s position, Mighty first reaches the caboose end, and desperately tries to stop the train by pulling backwards on the caboose’s bumper. He only succeeds in uncoupling the car, while the engine and remaining cars advance at full steam. Mighty now finds himself in a race with the careening train, inching forward car length by car length to reach the engine.

The crossing is only a short distance ahead, and Mighty still has not reached the cab. Instead, he darts under the train’s wheels. A crowd of the kids have reached the junction, and stand in shock and terror as the train passes them unabated, staring at car after car whizzing past, and seeing nothing of the slaughter that they presume is going on underneath. But as the last car passes, standing on the other side of the tracks is Mighty, carrying the formerly trapped boy in his arms, in the clear. The kids cheer and celebrate Mighty’s daring rescue of them all. The scene reurns to the classroom, where a short time has passed, and the students have turned over an entirely new leaf. Their old professor now receives a table fill of apples, candy, flowers, and thank you notes. The students, all dressed in boy scout uniforms, sing Good Morning with angel halos glowing above their heads. All except one in the back row, who, despite his boy scout uniform, is about to revert to his old ways by flinging an ink bottle at the teacher. He finds he is not alone, as Mighty appears, looking over his shoulder and shaking his head in disapproval. The little mouse is not about to challenge the wishes of his hero, and makes amends by smashing the ink bottle over his own head, leaving his face stained in bright blue, while he obediently finishes the song lyric, “Because we love our school”, for the fade out.

As promised, we both begin and end this sesion with Oscar nominees. From A to Z-Z-Z-Z (Warner, 10/16/54 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) presents the debut of Ralph Phillips, a typical little boy with an atypical overripe imagination, who seemed to become a recurring alter-ego for Chick, perhaps patterned after his own school day memories (to the tenth power). Ralph would make several reappearances at various age levels, including still as a boy in Boyhood Daze (1957). The Adventures of the Roadrunner (1962) and at a more mature age in the recruiting films 90 Day Wondering (1956) and Drafty, Isn’t It? (1957). He was voiced in this and his other childhood appearances by Dick Beals (a prolific voice-over artist who was able to turn a glandular disorder into an asset by becoming sought after for performing juvenile voices with a memorable read that never aged past puberty), in his first role for theatrical animation, though already well known in commercial circles as the voice of Speedy Alka-Seltzer. Many will also remember him from recurring TV voicings for Hanna-Barbera productions and Roger Ramjet cartoons, among others.

As promised, we both begin and end this sesion with Oscar nominees. From A to Z-Z-Z-Z (Warner, 10/16/54 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) presents the debut of Ralph Phillips, a typical little boy with an atypical overripe imagination, who seemed to become a recurring alter-ego for Chick, perhaps patterned after his own school day memories (to the tenth power). Ralph would make several reappearances at various age levels, including still as a boy in Boyhood Daze (1957). The Adventures of the Roadrunner (1962) and at a more mature age in the recruiting films 90 Day Wondering (1956) and Drafty, Isn’t It? (1957). He was voiced in this and his other childhood appearances by Dick Beals (a prolific voice-over artist who was able to turn a glandular disorder into an asset by becoming sought after for performing juvenile voices with a memorable read that never aged past puberty), in his first role for theatrical animation, though already well known in commercial circles as the voice of Speedy Alka-Seltzer. Many will also remember him from recurring TV voicings for Hanna-Barbera productions and Roger Ramjet cartoons, among others.

An average day at school finds the class reciting addition tables, while back row student Ralph looks out the window, his mind on more important things, as his eyelids droop while watching a bird in flight. Suddenly, the bird is transformed into Ralph himself, gracefully soaring through the skies without even the need to flap his wings, as he performs erial loops and backflips. His progress is stopped by a larger bird, who oddly begins to talk to him in perfect English. It is in reality the voice of his teacher, awakening him from his doze. “Well, Mr, Phillips, daydreaming again?”, she asks. Ralph straightens up in his seat, forcing his eyes wide open to simulate full attentiveness. “Oh, I’m so sorry. You were wide awake, werem’t you? Then perhaps you’ll show us how to solve the problem on the blackboard.” Ralph is forced to walk to the front of the class, where a column addition problem looms seemingly a mile high in chalk above him. Having no idea how to proceed, Ralph’s eyelids droop again, and the column of digits begins to quiver and vibrate – each one of the numbers deriding him with choruses of raucous laughter. Enter into the shot a hero, in the form of a chalk outline drawing of Ralph himself. Chalk Ralph tiptoes up to the addition problem, and pills out the operations bar from under the lowest set of digits – causing the whole problem to collapse into a heap of numbers at the base of the chalkboard. From the dogpile of digits springs a 5, holding up a closed-top 4 as if a sword.

Chalk Ralph seizes up a chalk stick, and a duel commences. Notable in this film is Jones’s capture of the character element of many little boys’ sense of absolute fearlessness, and complete insensitivity to acts of violence – as Chalk Ralph savagely thrusts the chalk srick through the lower cirve of the 5, mortally wounding the numeric creature, who collapses on the spot. Other numbers rise in outrage, and pursue the murderer. Chalk Ralph passes various letters of the alphabet written along the top edge of the blackboard, grabbing a capital D and Y. He transforms the Y by pushing its center shaft forward, bending its remaining arms backwards to take the shape of an arrow point. Then, he loads it into the D as if a bow, and fires at the oncoming numbers. He strikes another blow into the abdomen of an 8, defating its lower loop so that it also expires to its doom. Ralph reloads by grabbing a manuscript i and the dots off the i and j, loading the dots into the i as if a rifle barrel, and fires again, savagely blasting a chunk out of the curve of a 3, and keeps firing, until the teacher’s call of his name again awakens him, together with the laughter actually originating from his classmates, as he stands before the class simulating gunfire shots.

Chalk Ralph seizes up a chalk stick, and a duel commences. Notable in this film is Jones’s capture of the character element of many little boys’ sense of absolute fearlessness, and complete insensitivity to acts of violence – as Chalk Ralph savagely thrusts the chalk srick through the lower cirve of the 5, mortally wounding the numeric creature, who collapses on the spot. Other numbers rise in outrage, and pursue the murderer. Chalk Ralph passes various letters of the alphabet written along the top edge of the blackboard, grabbing a capital D and Y. He transforms the Y by pushing its center shaft forward, bending its remaining arms backwards to take the shape of an arrow point. Then, he loads it into the D as if a bow, and fires at the oncoming numbers. He strikes another blow into the abdomen of an 8, defating its lower loop so that it also expires to its doom. Ralph reloads by grabbing a manuscript i and the dots off the i and j, loading the dots into the i as if a rifle barrel, and fires again, savagely blasting a chunk out of the curve of a 3, and keeps firing, until the teacher’s call of his name again awakens him, together with the laughter actually originating from his classmates, as he stands before the class simulating gunfire shots.

The teacher suggests that maybe he needs some fresh air, and hands him a letter to deposit in a corner mailbox. Ralph exits the school with his precious cargo, and is quickly transformed again, into the form of a heroic, bearded Pony Express rider. Mounting a swift stallion, he takes off through dangerous territory to get his letter through. Quickly his trail is picked up by a tribe of savage Indians, who begin a non-stop assault of flying arrows at Ralph and his steed. Ralph counters with pistol fire, heartlessly knocking off his pursuers one by one. Ralph makes it into the walls of a remote fort, the only contents of which is a single mailbox, into which Ralph deposits the letter. He mounts up again for the return ride. This time, the Indians have brought up reinforcements, veritably filling the skies with flying arrows, so that Ralph returns to the school with the shafts of about a half dozen arrows sticking out of his back. This image of course fades away as Ralph enters the door of the school, where still stoop-shouldered and seeming on the verge of collapse, he tells the teacher, “Don’t you worry none about your ranch, Ma’am. The money for the mortgage has gone through.” He falls in exhaustion on the floor, while the perplexed teacher, amidst another round of student laughter, can only comment, “Umm, yeah.”

Listen for an audio “cameo” by Chuck Jones as one of the sailors in this scene

Ralph stands alone in a corner of the room, which transforms into the corner of a boxing ring in a fight arena. A bell souns for round one, and Ralph slowly advances toward an opponent six times his size. The opponent makes an underhanded swing to attempt to score a blow at Ralph’s low height level, but misses entirely, while Ralph scores a powerful punch into the opponent’s breadbasket. Ralph follows up with an upper cut, then a direct blow to the face, knocking the opponent entirely out of the frame, and stands in a victorious pose as a bell sounds again. (Compared to other chapters of this epic, this daydream seems surprisingly short. Obe can only wonder if the original storyboard extended the fight to the same length as the other dreams, and time constraints prevented its full inclusion in the final film.) Ralph once again hears his name called, and drifts back to the classroom, where the teacher asks, “What’s the matter dear? Didn’t you hear the bell? Don’t you want to go home?” Before responding, Ralph advances to the classroom door, transforming into the medal-studded outfit of General Douglas MacArthur, and pauses in the doorway to repeat the General’s famous quote, “I shall return!” Indeed he did, in the follow-ups discussed above.

Ralph stands alone in a corner of the room, which transforms into the corner of a boxing ring in a fight arena. A bell souns for round one, and Ralph slowly advances toward an opponent six times his size. The opponent makes an underhanded swing to attempt to score a blow at Ralph’s low height level, but misses entirely, while Ralph scores a powerful punch into the opponent’s breadbasket. Ralph follows up with an upper cut, then a direct blow to the face, knocking the opponent entirely out of the frame, and stands in a victorious pose as a bell sounds again. (Compared to other chapters of this epic, this daydream seems surprisingly short. Obe can only wonder if the original storyboard extended the fight to the same length as the other dreams, and time constraints prevented its full inclusion in the final film.) Ralph once again hears his name called, and drifts back to the classroom, where the teacher asks, “What’s the matter dear? Didn’t you hear the bell? Don’t you want to go home?” Before responding, Ralph advances to the classroom door, transforming into the medal-studded outfit of General Douglas MacArthur, and pauses in the doorway to repeat the General’s famous quote, “I shall return!” Indeed he did, in the follow-ups discussed above.

Here’s an edited sample:

We, too, shall return next week.