Dissolving Genre: Toward Finding New Ways to Write About the World

Perhaps it is raining, the river in winter roar, breaking from the spine of its straightened banks and stretching flood arms out across our paddocks. The river has been farmed for only a hundred years. I am almost a teenager. Inside our Wairarapa farmhouse my father shows me his copy of the Tao Te Ching from the 1970s. “Nothing is more soft and yielding than water. / Yet for attacking the solid and strong, nothing is better.” Outside the river rips up fence posts and wires. The next day my mother, at her most anarchic, will have us three kids out there rafting on tractor tire inner tubes. We rise and soar with the wild waters, which resemble nothing we could ever own.

*

Three decades later, in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, a city surrounded by sea, I find my writing bending and yielding as I seek ways to evoke being part of the nonhuman world. Finding ways to do this feels increasingly urgent, an urgency at odds with my lean to the gentle and discursive. My writing becomes watery in content and form. I write a memoir shaped by immersions in different rivers and oceans and in the chilly city bays near where I live. I call it a cycle of essays. I call it Where We Swim. Oceans rise. Rivers become toxic to animals—human and nonhuman alike. My sense of family keeps rippling outward, from the uncanny of sibling relationships stretched between continents, to whales and Amazonian manatee, to elks and ibises, to rocks and waves.

One essay begins with an image of my elder brother and me and our own children shining wet in the Indian Ocean of Western Australia, where he has gone to live. But the essay finds its meaning in an encounter with a pod of humpback whales, close enough for us to hear their exhalations of wet breath, and in the question of what it means to think of whales, too, and the waters they swim, as part of the fluid families we all inhabit, broad and strange.

As I write about my brother’s family and my own, I watch footage of whales, seeing the way even the most enormous adult appears light as he soars through water, the way a calf sleeps on its mother’s back, and the way one whale’s long white throat grooves curve and stretch, concertina-like as, remaking grace, they leap, from water. Droplets spray out and fall.

The whistles and grunts that make up humpback whales’ songs are the longest and most complex rhythmic syntax in the non-human world. One whale takes a song from another and returns it with a new rhythm of its own. Humpbacks pass song fragments across hundreds of miles. I wonder what those songs sound like when humpbacks meet again after a gap of time. What sounds do they float to acknowledge and guide one another? How does it feel to become a drop of water, and then to re-enter, to dissolve back into the whole?

It is now more than three years since I saw my other brother. Living in South America he is now unable to come home. I dream of the waters pulling between.

I am riding the upswell of all the creative nonfiction now trying to reimagine the relationship between the human and non-human worlds.I try to write the encounter with the water and the whales in a way that their movements and stories will have at least the weight of my human narrative, no current in the writing reduced to metaphor for another. I think about the ways whales have been hunted almost to extinction, waters slicked, and of my own history as Pākehā, European New Zealander, my ancestors sailing seas to make our homes in already inhabited river mouths.

I imagine the braided essay as a braided river, networks of channels flowing in and out of one another. Now this in turn helps me apprehend how river currents mix and change, finding new routes as they descend. How they spread across rocky plains, patterns of shifting gravel beds making and re-making whole ecosystems, rich with life, moving always toward the sea.

*

By this point I am riding the upswell of all the creative nonfiction now trying to reimagine the relationship between the human and non-human worlds, drawn always in my own imaginings to water as a vessel of connection. Like many of us, once I did not really read what gets called “nature writing,” thinking of it as inevitably boring, elegiac, pious. But I read this new wave of bending, resistant writing, as though my life depends on it. Perhaps it does.

Nature is not sectioned off in this nonfiction, not treated as though it were separate from daily lives, or as though shared survival was not the most intimate thing imaginable.

I make lists of recent books—for myself and for my nonfiction students and then for the students in a new course I write with a colleague, Laura-Jean McKay, on eco-fictions and nonfictions: Joanna Pocock, Surrender: the Call of the American West (2019), Rebecca Giggs, Fathoms: the World in the Whale (2020), Nicole Walker, Sustainability: A Love Story (2018), Sophie Cunningham, City of Trees: Essays on Life, Death and the Need for a Forest (2019). I keep reading and listing Robert Macfarlane and Rebecca Solnit, whose writing in some ways brought me here. I read everything in the Sydney Review of Books New Nature series. I notice how much some fiction now sounds like creative nonfiction, as though in a novel like Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020) the fiction writer has turned to first-person nonfiction to find a voice and form adequate to our inundating reality. A form fit to weather the 21st century.

Together, my students and I make lists of the meanings and methods of the new modes of what we are now calling eco-nonfiction. These come to include:

Close observation and attention

this kōwhai bloom, that estuary,

this possum, that coal fire.

Ordinary or unpromising locations

edgelands,

the flourishing of motorway burbs.

Avoids idealization of pristine wilderness areas

fewer epiphanies in National Parks,

fewer men on mountains.

Favors ecosystems that include humans

more suburbs, kitchens, children, parents…

but also gardens, rivers, oceans, oysters.

Observes altered worlds

eucalypts in San Francisco

ice melt in Antarctica

rewildings

and sometimes lost worlds

endling: an animal that is the last of its species.

Often draws on memoir

I, sometimes we.

Finds continuities between the human and nonhuman

warm breath misting.

Demands we move outside a human frame of reference

“Is it possible to draw or write a forest?”

Struggles with how to do this

signed here.

Searches for organic forms and structures opening out stories of confluence

“What do I know but pieces, all at once?”

Understands that in the 21st century “to write about nature is a political act”

Hopes (within hopes) that a shift in attention

–a yielding of consciousness to a world beyond human–

will give to a shift in action.

I wait impatiently for works of eco nonfiction I know are being written at the same time as my own in the place I inhabit, Aotearoa New Zealand. Nina Mingya Powles’ Small Bodies of Water (2021) arrives just after a pandemic lockdown, on the first day in weeks when we can legally swim. I take it to the rocky shore.

I imagine the braided essay as a braided river, networks of channels flowing in and out of one another.Powles’ background is different from my own. She is white and Malaysian Chinese. Born in Aotearoa, she partly grew up in China, and now lives in London. Her book won the 2020 Nan Shepherd Prize in the United Kingdom for Underrepresented Voices in Nature Writing. She writes as someone, “whose skin, whose lineage, is split along lines of migration.” It takes me some time to remember—to see—this is also true of my own lineage, although the very fact I can forget it comes from a place far more than my white skin deep.

Powles finds one home in the Māori word “tauiwi,” non-Māori, non-Indigenous, and the ongoing question of how to “put down roots on stolen land” in ways that are intentional, neither violent and appropriative, nor leaving one “drifting, rootless, untethered.” She is writing of peoples here, but I also think of our relationships with other non-human life of this planet, and how it owns itself. And I turn over that phrase we use of “putting down roots.” How would it sound differently if rooted underwater, as in a riverbed, held in place but alive with movement? Awash.

I recognize Powles’s observation that she never intended to write about “ecological loss,” “but I also don’t know how to avoid writing about it.” It does not seem strange that we were writing our watery books concurrently. We were both in search of forms adequate to evoke multiple coeval experiences. Our books are not so much braided as cartographic—oceanographic, drawing diverse bodies of water together, overflowing distinct embodied experiences and places into one another.

From accumulation of close observations, eventually, there comes abundance, and the possibility of some kind of hope.

Looking up through my goggles I see rainforest clouds, a watery rainbow. I can see the undersides of frangipani petals floating on the surface, their gold-edged shadows moving towards me. I straighten my legs and point my toes and launch myself towards the sun.

Back at the top of the steep hill on which I live for now, Nic Low’s Uprising: Walking the Southern Alps of New Zealand (2021) arrives too. Low is of Ngāi Tahu and European descent and divides his time between Melbourne and Ōtautahi Christchurch. For Low, it is walking rather than swimming that is his mode of observation and way of knowing, but the modes share an approach of embodied immersion. Low’s writing finds its shape in nine crossings of Kā Tiritiri-o-te-moana, the mountain range that forms the spread spine of the South Island of Aotearoa and of the Ngāi Tahu tribe’s territory. His ancestral maps are here, in the streaming mountains.

As Low narrates his journeys with various traveling companions, he interweaves the stories of previous mountain voyages, by Māori, by early European colonists, by later human arrivals, but also by atua (Māori gods), and by the land itself. “We understand the landscape through whakapapa: complex genealogies that connect us to each other, and to the land, and to the atua,” he writes. Ngāi Tahu’s oldest terrestrial ancestor is Aoraki, the highest mountain in Aotearoa, who came down from the heavens with his brothers to meet his new stepmother, Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother. They became stranded, waiting for rescue on the upturned hull of their canoe, slowly turning to stone. When their rescue party found and grieved for them, they also forged gorges to the sea. For Low, to walk and write and address the land, with its waters and rocks and golden-brown tussock, is to inhabit a world where there is no solid line between history and myth, human and non-human. “On a narrow island, all journeys begin and end with the sea.”

In other places and in other modes, I have written about the politics of traditions of writing in Aotearoa, as in many settler-colonial countries (certainly in the United States, Canada and Australia), which prize a particular idea of wilderness areas as unpeopled and unoccupied. Writing like Low’s helps me open out further to ways of knowing and storying that show how “rather than wilderness,” even mountains are full of history “everywhere you look.” Rivers are ancestors, food sources and highways. Low’s own writing is an act of map-making and re-storying, of homecoming both individual and collective. It is writing that is not about the land, so much as of the land, from the stones of the sentence to the upper strata of structure:

Toitū te whenua, you often hear—translated as “leave the land undisturbed.” How could you, when you were going to be part of the land yourself? The better sentiment is “cleave to the land.” I dug into the loam, looking for bones, gathering history in dirty half-moons beneath my nails.

The scent of brine grew stronger, and finally in the late afternoon we passed through a break in the trees to reach the shore. After so long enclosed in dense bush, the wide ocean vista was a startling relief. We hugged and splashed saltwater on our chapped faces… Sea haze softened the edges of the land.

What I keep coming back to with a question is that term attack, sometimes translated as “overcoming”: Nothing is more soft and yielding than water. Yet for attacking the solid and strong, nothing is better. What I see is water flowing through rigid social structures, seeping into a seeming collective belief that we must pour concrete, raise steel to the sky, buy primary-colored lego in bright plastic boxes, wear tailored trousers. Perhaps the very threat of water, of floods on a scale we can as yet hardly imagine, might help us instead to seek more yielding ways to live alongside and within the non-human world. To soften with it, from the page into the ground.

__________________________________

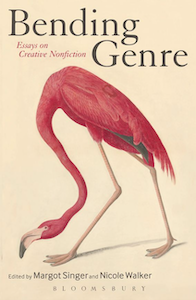

This essay is forthcoming in Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction, from Bloomsbury, and will be titled ”Dissolving Genre: Writ with Water.”