Flights of Fancy (Part 11): Above and Beyond the Call

I’ve never seen a statistic on enlistments during WWII as to whether early inductees, upon reaching the one year anniversary of their recruitment, were allowed to return to civilian life on schedule as in Wolf Chases Pigs, or whether laws were altered to keep them in the service for the duration. For that matter, if leaving was permitted after a year, how many soldiers chose to do so, or did the vast majority of them feel pressured to sign up for another term? Whatever the situation, the war dragged on into its second year, with no visible letup in the paranoia of fear of attack, or the fury to settle the score with the Hun. Hollywood’s cartoons continue to mirror these national sentiments. It seemed like a third to a half of the output from this time was at least marginally war-related. Leading characters from two studios (Donald Duck from Disney, and Gandy Goose and Sourpuss from Terrytoons), were serving out substantial portions of their screen time in khaki, while Popeye continued to adapt to Navy whites. And throughout their adventures, the planes continued to fly in close formation.

Scrap the Japs (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 11/20/42 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye’s still in the service, and in this banned cartoon meets the enemy face to face. As usual, he is in trouble, and for negligence in jumping out of a plane without a parachute, is assigned duties to swab the whole carrier. He makes things easier for himself with a little ingenuity. Tying two mops to the propeller blades of a small aircraft, and connecting a watering can to the machine gun, Popeye douses and mops the deck in automatic fashion with ease. He takes care of sweeping by hiding the collected dust under the corner of one of the gun turrets. These endeavors are suddenly interrupted by a dropping of bombs close to the ship, seemingly from within a small, mysterious passing cloud. A command sounds over the ship’s loudspeakers for all planes to take off with full equipment to investigate and intercept. Popeye is in such a hurry to get his craft aloft, he makes a turn off of the carrier deck, leaving the cockpit entirely, while his plane flies on straight ahead. As usual, through sheer cartoon will, he catches the plane and regains charge over the controls, beginning his scouting. Commenting on the enemy’s favorite fighter, he mumbles to himself, “A ‘Zero’ means naught to me.” Suddenly, the mystery cloud appears again. From Popeye’s two-dimensional viewpoint, it appears to just be an everyday weather phenomenon – but from its backside, we see that it is nothing but a flat piece of wooden stage scenery, with inscription reading “Made in Japan”. The fake front is attached in a pivot around the fuselage of a small Zero fighter, on extension poles long enough to extend around the plane’s wingspan, so that it can be rotated in any direction to prevent the plane from being seen. The plane pulls some fancy maneuvers, opening a hatch in its “cloud cover” and revealing a cannon, complete with robotic hand to draw a target on Popeye’s aviator’s cap, then bounce several cannonballs off his head. Impervious to the firepower, Popeye remarks, “That sounded like thunder.” The plane capitalizes on Popeye’s notion by pouting a little “rain” on him with a watering can, but takes another pot shot at his wing. “That cloudburst looked suspicious”, mutters Popeye. Popeye plays an aerial game of cat and mouse, trying to maneuver himself above, below, and on both sides of the cloud for a better view, but always receives the same view pivoting to meet his every move. Only when Popeye flies rings around the fighter is the pilot unable to keep up speed to maintain his cloudy disposition, and his screen falls just long enough to reveal his presence. “So sorry”, the pilot bows. “You will be, ya storm trooper”, yells Popeye. Taking aim at the enemy plane with his own guns, Popeye delivers a blast that reduces the aircraft to only motor and prop. A second blast leaves the pilot dancing upon the engine’s drive shaft to keep the cylinders firing. A third shot leaves him with just the propeller and its shaft, log-rolling upon the shaft’s diameter to keep it spinning. “Somebody’s rising sun has fallen”, chuckles Popeye, as he turns his plane into a dive to follow the pilot down. He steps out onto his wing to sock a “Jap pan”, but forgets himself and walks out onto thin air. He pulls his parachute cord – only to reveal numerous articles of clothing tied to a line. “My gosh. My wash!”, shouts the sailor. Grabbing an old boot, he is just able to hold it open far enough to serve as a substitute chute, while the enemy pilot continues to run on the propeller shaft to get away. “I never seen a Jap that wasn’t yellow!”, yells Popeye, in his most politically incorrect line of the film.

Scrap the Japs (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 11/20/42 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye’s still in the service, and in this banned cartoon meets the enemy face to face. As usual, he is in trouble, and for negligence in jumping out of a plane without a parachute, is assigned duties to swab the whole carrier. He makes things easier for himself with a little ingenuity. Tying two mops to the propeller blades of a small aircraft, and connecting a watering can to the machine gun, Popeye douses and mops the deck in automatic fashion with ease. He takes care of sweeping by hiding the collected dust under the corner of one of the gun turrets. These endeavors are suddenly interrupted by a dropping of bombs close to the ship, seemingly from within a small, mysterious passing cloud. A command sounds over the ship’s loudspeakers for all planes to take off with full equipment to investigate and intercept. Popeye is in such a hurry to get his craft aloft, he makes a turn off of the carrier deck, leaving the cockpit entirely, while his plane flies on straight ahead. As usual, through sheer cartoon will, he catches the plane and regains charge over the controls, beginning his scouting. Commenting on the enemy’s favorite fighter, he mumbles to himself, “A ‘Zero’ means naught to me.” Suddenly, the mystery cloud appears again. From Popeye’s two-dimensional viewpoint, it appears to just be an everyday weather phenomenon – but from its backside, we see that it is nothing but a flat piece of wooden stage scenery, with inscription reading “Made in Japan”. The fake front is attached in a pivot around the fuselage of a small Zero fighter, on extension poles long enough to extend around the plane’s wingspan, so that it can be rotated in any direction to prevent the plane from being seen. The plane pulls some fancy maneuvers, opening a hatch in its “cloud cover” and revealing a cannon, complete with robotic hand to draw a target on Popeye’s aviator’s cap, then bounce several cannonballs off his head. Impervious to the firepower, Popeye remarks, “That sounded like thunder.” The plane capitalizes on Popeye’s notion by pouting a little “rain” on him with a watering can, but takes another pot shot at his wing. “That cloudburst looked suspicious”, mutters Popeye. Popeye plays an aerial game of cat and mouse, trying to maneuver himself above, below, and on both sides of the cloud for a better view, but always receives the same view pivoting to meet his every move. Only when Popeye flies rings around the fighter is the pilot unable to keep up speed to maintain his cloudy disposition, and his screen falls just long enough to reveal his presence. “So sorry”, the pilot bows. “You will be, ya storm trooper”, yells Popeye. Taking aim at the enemy plane with his own guns, Popeye delivers a blast that reduces the aircraft to only motor and prop. A second blast leaves the pilot dancing upon the engine’s drive shaft to keep the cylinders firing. A third shot leaves him with just the propeller and its shaft, log-rolling upon the shaft’s diameter to keep it spinning. “Somebody’s rising sun has fallen”, chuckles Popeye, as he turns his plane into a dive to follow the pilot down. He steps out onto his wing to sock a “Jap pan”, but forgets himself and walks out onto thin air. He pulls his parachute cord – only to reveal numerous articles of clothing tied to a line. “My gosh. My wash!”, shouts the sailor. Grabbing an old boot, he is just able to hold it open far enough to serve as a substitute chute, while the enemy pilot continues to run on the propeller shaft to get away. “I never seen a Jap that wasn’t yellow!”, yells Popeye, in his most politically incorrect line of the film.

Below waits a Japanese salvage scow, with a crew collecting any available flotsam for parts. The pilot comes in for a landing, and the crewmen quickly grab various pieces of scrap to create for him a new plane. Popeye lands with a crash upon the deck, bouncing most of the ship’s metal supply overboard. The crew gangs up to take it out upon the sailor, and mobs him in a dogpile, until Popeye produces his spinach can and downs his usual dose, tossing the empty can overboard. To his surprise, he doesn’t have to do battle with the crew, as they all leap into the sea, trying to catch up with the sinking spinach can, as more “Scrap iron!” But reinforcements are nearby, in the form of a Japanese battleship. A shot from its main gun hits the stern of the scow, but Popeye takes advantage of the shot’s momentum, steering the ship from its anchor line to turn, aiming the scow directly at the battleship. Leaping on the larger ship’s deck, Popeye performs somersaults, socking one after another of the enemy sailors with each of his rotating arms and legs. Four of the sailors land in and plug up the barrels of the gun turret, while several more make holes right through sheet metal of the command bridge, the holes forming the shape of a V and dot dot dot dash. Next, Popeye rips off the ship’s rear railing, bending it into the shape of a can-opener key like one would find on a can of sardines or canned ham. Inserting the “key” in the deck, he makes a full turn around the ship’s perimeter, breaking off a winding strip of metal from the ship’s deck. Popeye playfully positions himself atop the spiral of metal, and pulls out an ice cream cone to enjoy as he watches the fun. The deck and all superstructure of the ship cave in on cue, leaving nothing but the crater of the ship’s hull to be seen. In the final shot, Popeye flies back to his ship, with a tow rope fastened to his plane. Popeye’s been doing some more fancy metalwork, as in tow behind him is the salvage scow, but with a new feature added to its deck – the form of a giant rat trap, with the crews of both vessels shouting in gibberish as captives inside.

Below waits a Japanese salvage scow, with a crew collecting any available flotsam for parts. The pilot comes in for a landing, and the crewmen quickly grab various pieces of scrap to create for him a new plane. Popeye lands with a crash upon the deck, bouncing most of the ship’s metal supply overboard. The crew gangs up to take it out upon the sailor, and mobs him in a dogpile, until Popeye produces his spinach can and downs his usual dose, tossing the empty can overboard. To his surprise, he doesn’t have to do battle with the crew, as they all leap into the sea, trying to catch up with the sinking spinach can, as more “Scrap iron!” But reinforcements are nearby, in the form of a Japanese battleship. A shot from its main gun hits the stern of the scow, but Popeye takes advantage of the shot’s momentum, steering the ship from its anchor line to turn, aiming the scow directly at the battleship. Leaping on the larger ship’s deck, Popeye performs somersaults, socking one after another of the enemy sailors with each of his rotating arms and legs. Four of the sailors land in and plug up the barrels of the gun turret, while several more make holes right through sheet metal of the command bridge, the holes forming the shape of a V and dot dot dot dash. Next, Popeye rips off the ship’s rear railing, bending it into the shape of a can-opener key like one would find on a can of sardines or canned ham. Inserting the “key” in the deck, he makes a full turn around the ship’s perimeter, breaking off a winding strip of metal from the ship’s deck. Popeye playfully positions himself atop the spiral of metal, and pulls out an ice cream cone to enjoy as he watches the fun. The deck and all superstructure of the ship cave in on cue, leaving nothing but the crater of the ship’s hull to be seen. In the final shot, Popeye flies back to his ship, with a tow rope fastened to his plane. Popeye’s been doing some more fancy metalwork, as in tow behind him is the salvage scow, but with a new feature added to its deck – the form of a giant rat trap, with the crews of both vessels shouting in gibberish as captives inside.

A Tale of Two Kitties (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Tweety), 11/21/42 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Bud Abbott and Lou Costello were certainly no stranger to the service comedy. By the time this film was made, they had already scored big-time for Universal as “Buck Privates”, then “In the Navy”, and were about to conquer the third branch of the services with “Keep ‘Em Flying”. As Hollywood’s “new kids on the block” in comedy teams, their names were rapidly becoming household words, and their personas were ripe subjects for cartoon parody. Universal itself had already recognized this, by having Woody Woodpecker adopt Costello’s reactive whistle in “Ace in the Hole”, discussed previously. So it was only a matter of time before a full cartoon would be devoted to their new style of humor and verbal interplay – and Bob Clampett chose to be among the first to do so.

A Tale of Two Kitties (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Tweety), 11/21/42 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Bud Abbott and Lou Costello were certainly no stranger to the service comedy. By the time this film was made, they had already scored big-time for Universal as “Buck Privates”, then “In the Navy”, and were about to conquer the third branch of the services with “Keep ‘Em Flying”. As Hollywood’s “new kids on the block” in comedy teams, their names were rapidly becoming household words, and their personas were ripe subjects for cartoon parody. Universal itself had already recognized this, by having Woody Woodpecker adopt Costello’s reactive whistle in “Ace in the Hole”, discussed previously. So it was only a matter of time before a full cartoon would be devoted to their new style of humor and verbal interplay – and Bob Clampett chose to be among the first to do so.

While marking the first of several Warner shorts in which the team’s personalities would be milked, this film was more importantly a first for an unassuming little character who would grow to become a Looney Tunes screen legend and a certifiable trademark personality in his own right – Tweety. Though not yet qualifying as fully-fledged (mainly because of the restrictions of mother nature, his feathers having not yet grown in upon his body), Tweety’s signature speech patterns and hidden spunk/talent for outwitting “putty tats” are already intact, though his signature line “I tawt I taw…”is delivered in his first few films in a slightly more prolonged read than audiences later became used to. He was, nevertheless, a work in progress. His name had not yet been selected, and would not be worked out until the subsequent “Birdy and the Beast”. Clampett’s original story sketches actually refer to his name as “Orson”. Nor was there any inclination as yet to set up a partnership between the bird and any particular cat as a comedy team. Sylvester is nowhere to be seen, and would not appear together with Tweety in any of Clampett’s films. This is curious, as Clampett’s unit was in fact also be responsible for the creation of Sylvester, originally black-nosed, in Porky Pigs “Kitty Cornered”. But Clampett did not seem to know what to do with the cat character, and largely let him languish or be passed off to other directors, with the brainstorm for a character pair-up having to wait until Clampett’s departure from the studio, and nurturing in the fertile mind of studio veteran Friz Freleng. The eventual pairing spawned a dependable audience attraction that would last nearly until the closure of the official Termite Terrace studio.

While marking the first of several Warner shorts in which the team’s personalities would be milked, this film was more importantly a first for an unassuming little character who would grow to become a Looney Tunes screen legend and a certifiable trademark personality in his own right – Tweety. Though not yet qualifying as fully-fledged (mainly because of the restrictions of mother nature, his feathers having not yet grown in upon his body), Tweety’s signature speech patterns and hidden spunk/talent for outwitting “putty tats” are already intact, though his signature line “I tawt I taw…”is delivered in his first few films in a slightly more prolonged read than audiences later became used to. He was, nevertheless, a work in progress. His name had not yet been selected, and would not be worked out until the subsequent “Birdy and the Beast”. Clampett’s original story sketches actually refer to his name as “Orson”. Nor was there any inclination as yet to set up a partnership between the bird and any particular cat as a comedy team. Sylvester is nowhere to be seen, and would not appear together with Tweety in any of Clampett’s films. This is curious, as Clampett’s unit was in fact also be responsible for the creation of Sylvester, originally black-nosed, in Porky Pigs “Kitty Cornered”. But Clampett did not seem to know what to do with the cat character, and largely let him languish or be passed off to other directors, with the brainstorm for a character pair-up having to wait until Clampett’s departure from the studio, and nurturing in the fertile mind of studio veteran Friz Freleng. The eventual pairing spawned a dependable audience attraction that would last nearly until the closure of the official Termite Terrace studio.

The film follows a day’s adventures in the life of alley cats Babbitt and Catstello, from the crack of dawn until far into the night, as Babbitt attempts to talk the gullible Catstello into doing all the dirty work of catching their morning breakfast – a baby bird in a nest high above. As Catstello is made to overcome his fear of high places by being stuck with a pin by his partner to get him up a tall ladder, Babbitt instructs him to “Give me the bird.” Speaking to the audience. Catstello remarks, “If the Hays’ Office would only let me, I’d give him the bird, all right.” (Reference to Will Hays, head of censorship for motion pictures, and to the colloquial use of the phrase “the bird” to refer to a flatulent-sounding raspberry – a no-no for most cartoons of the time, though an oft-repeated gag pre-1935.) Among the various misadventures from the cat’s efforts to catch the soon-to-be canary is a memorable and well-timed sequence where Catstello repeatedly bounces up to the nest while wearing springs on his feet. Each new bounce is met with move and countermove by the bird and cat to outwit and/or deliver painful consequences to the other. A highlight has Tweety dousing the cat’s face on each bounce with a spray of seltzer water from a bottle. Catstello reyurns on the next bounce, having obtained from nowhere a deep sea diver’s helmet, and sticks his tongue out at Tweety from behind the safety of the helmet’s glass face panel. By the next bounce, Tweety is ready for him, and opens the helmet’s glass window just long enough to stick a firecracker inside with the cat. Before the next bounce, an an explosion has been heard, and Catstello’s face is a wreck. The entire sequence was lifted almost verbatim by Freleng for the later Sylvester and Tweety pair-up, “Bad Ol’ Putty Tat” – perhaps on the speculation that the later film was more likely to get repeat bookings than the earlier formative effort.

The film follows a day’s adventures in the life of alley cats Babbitt and Catstello, from the crack of dawn until far into the night, as Babbitt attempts to talk the gullible Catstello into doing all the dirty work of catching their morning breakfast – a baby bird in a nest high above. As Catstello is made to overcome his fear of high places by being stuck with a pin by his partner to get him up a tall ladder, Babbitt instructs him to “Give me the bird.” Speaking to the audience. Catstello remarks, “If the Hays’ Office would only let me, I’d give him the bird, all right.” (Reference to Will Hays, head of censorship for motion pictures, and to the colloquial use of the phrase “the bird” to refer to a flatulent-sounding raspberry – a no-no for most cartoons of the time, though an oft-repeated gag pre-1935.) Among the various misadventures from the cat’s efforts to catch the soon-to-be canary is a memorable and well-timed sequence where Catstello repeatedly bounces up to the nest while wearing springs on his feet. Each new bounce is met with move and countermove by the bird and cat to outwit and/or deliver painful consequences to the other. A highlight has Tweety dousing the cat’s face on each bounce with a spray of seltzer water from a bottle. Catstello reyurns on the next bounce, having obtained from nowhere a deep sea diver’s helmet, and sticks his tongue out at Tweety from behind the safety of the helmet’s glass face panel. By the next bounce, Tweety is ready for him, and opens the helmet’s glass window just long enough to stick a firecracker inside with the cat. Before the next bounce, an an explosion has been heard, and Catstello’s face is a wreck. The entire sequence was lifted almost verbatim by Freleng for the later Sylvester and Tweety pair-up, “Bad Ol’ Putty Tat” – perhaps on the speculation that the later film was more likely to get repeat bookings than the earlier formative effort.

The night sequences of the film return to our central theme, much in the manner of “Goofy’s Glider”, as Babbitt’s latest idea is to strap wooden boards onto Catstello’s arms as wings, and launch him skyward by means of a giant slingshot. Once aloft, Catstello remarks, “Hey, Babbitt, I’m a Spitfire!”, and litterally spits out sparks from his lips. He zooms past the nest of Tweety, who ducks, then rises from the nest wearing an air raid warden helmet. He produces a phone from nowhere (never knew the phone company services nests), and places a call. “Hewwo? Force Interteptor Command? I see an unidentified object fwying awound my wittle head.” Suddenly the sky is filled with searchlights, all trained on Catstello – as are a battery of anti-aircraft guns. They begin firing, as Catstello hopelessly attempts to dodge the bullets. All action pauses for a brief instant, permitting Catstello to question the audience, “Is there an insurance salesman in the house?” Catstello begins to fall, straight toward the tines of a pitchfork protruding upwards from a haystack below. When it seems apparent he is about to get the “point”, Catstello impossibly pots on the brakes, shifts himself at a right angle sideways to move his posterior away from the pitchfork, then resumes falling, right on top of Babbitt. Little Tweety passes in front of them, calling out, “Air waid. Wights out. Total bwackout”, then asides to the two cats, “Bweak it up, putty tats, bweak it up.” Babbitt whispers to Catstello, “Hey, now’s our chance”, and he and Catstello creep forward to pounce upon Tweety. But Tweety stops them in their tracks, reacting to their large, gleaming eyes, by shouting “TURN OUT THOSE LIGHTS!!” The two cats patriotically oblige, as the whites of their eyes turn to darkness, and even the moon goes out at Tweety’s command, for an abrupt ending to the film.

Barney Bear’s Victory Garden (MGM, Barney Bear, 12/26/42 – Rudolf Ising, dir.), falls into out survey for one memorable gag sequence. Barney is attempting to prepare the soil in his back yard for planting. But it is hard as a rock, and dry as a bone. It is so tough, it either bends Barney’s digging tools, or gets stuck around them, causing massive chunks of the stuff to be uprooted all at once, leaving a crater in the ground. Barney tries the modern method of a jack hammer, but is still having little success in breaking ground, when along comes a passing trio of U.S. bombing planes. Barney decides to enlist their help, by taking sacks of various varieties of potting soil and combining them with what excavation he has been able to complete, forming an image on the ground of a giant face of Adolf Hitler. Sighting this unusual scene, the bomber pilots can’t resist doing what pilots do – dropping a payload of bombs upon the image, blasting apart the topsoil into neat furrowed rows and a square patch, to resemble the stars and stripes of our flag. The soil job now well accomplished, Barney waves a cheery “Thank you” to the passing pilots as they fly on.

Barney Bear’s Victory Garden (MGM, Barney Bear, 12/26/42 – Rudolf Ising, dir.), falls into out survey for one memorable gag sequence. Barney is attempting to prepare the soil in his back yard for planting. But it is hard as a rock, and dry as a bone. It is so tough, it either bends Barney’s digging tools, or gets stuck around them, causing massive chunks of the stuff to be uprooted all at once, leaving a crater in the ground. Barney tries the modern method of a jack hammer, but is still having little success in breaking ground, when along comes a passing trio of U.S. bombing planes. Barney decides to enlist their help, by taking sacks of various varieties of potting soil and combining them with what excavation he has been able to complete, forming an image on the ground of a giant face of Adolf Hitler. Sighting this unusual scene, the bomber pilots can’t resist doing what pilots do – dropping a payload of bombs upon the image, blasting apart the topsoil into neat furrowed rows and a square patch, to resemble the stars and stripes of our flag. The soil job now well accomplished, Barney waves a cheery “Thank you” to the passing pilots as they fly on.

This is a short clip:

Scrap For Victory (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose, 1/22/43 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), receives only a mere honorable mention. Private Gandy and Sergeant Sourpuss are relegated to non-entities in this title, getting no chance to exhibit their personality quirks or to spark up mischief. Instead, they just play representative G.I. Joes, fighting at the front lines, but running out of ammunition. Sourpuss tells Gandy the folks at home won’t let them down, and to radio Washington. From the capital building emerge a legion of newsboys, circulating Extras about scrap needed for the war. The remainder of the film is a series of random spot gags of various animals collecting scrap, followed by a foundry sequence where tanks and planes emerge fully produced. Back at the battlefield, Gandy and Sourpuss look up in the sky, cheer, and stand in a salute, as row upon row of planes fly above in a red, white and blue sky, providing the needed air support. (Watch for an animation error that somewhat blows the impressiveness of this shot, as one plane to the far right of the screen keeps periodically disappearing for a frame.)

Pedro (Disney, RKO, 2/6/43 – Hamilton Luske, dir.), is a segment taken from Disney’s featurette, Saludos Amigos, the studio’s first venture in support of the nation’s “Good Neighbor Policy” of supporting its South American allies. It is also the root of the studio’s later series of efforts to personify inanimate objects and vehicles – a throwback, if you will, to 1930’s styles – that has led to even the relatively recent CGI franchises “Cars” and “Planes” in conjunction with Pixar. It also paved the way for many subsequent celebrated and imaginative shorts of the same ilk, such as “Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnet”, “Little Toot”, “The Little House”, and “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”.

Pedro (Disney, RKO, 2/6/43 – Hamilton Luske, dir.), is a segment taken from Disney’s featurette, Saludos Amigos, the studio’s first venture in support of the nation’s “Good Neighbor Policy” of supporting its South American allies. It is also the root of the studio’s later series of efforts to personify inanimate objects and vehicles – a throwback, if you will, to 1930’s styles – that has led to even the relatively recent CGI franchises “Cars” and “Planes” in conjunction with Pixar. It also paved the way for many subsequent celebrated and imaginative shorts of the same ilk, such as “Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnet”, “Little Toot”, “The Little House”, and “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”.

In Santiago, Chile, a family of planes resides at an airfield for delivery of mail across the Andes mountains to Mendoza, Argentina. A papa plane who carries the mail, a mama plane, and little Pedro, who is still nursing from a gasoline pump shaped like a baby bottle. Pedro attends Ground School, learning the basis such as reading, skywriting, and arithmetic, plus one of his least favorite subjects – geography. One day, papa develops a cold in his cylinder head. Mama can’t fly the high-altitude flight over the Andes, as she has high oil pressure. So Pedro is chosen for his first solo mission, with warning to stay away from the forbidding peak of Aconcagua. The fledgling flier has difficulty attaining flight speed, and nearly knocks the control tower off its supporting poles.

Pedro begins a long spiral ascent upwards to the entrance to a high mountain pass providing his flight route. He gets caught in a surprise downdraft at the pass’s entrance, but pulls out of it quickly like a veteran. His first trip through the pass is largely uneventful, although he gets a glimpse of Aconcagua from a distance, and tiptoes past it, concealed inside a small cloud. Spiraling down to Mendoza, he receives a mail pouch, which he carries on one wing. Hearing encouraging compliments from the film’s narrator about being ahead of schedule, Pedro begins showing off with some aerial acrobatics – then comes face to face with a buzzard, who gives him a little razz, then turns tail on him. Pedro playfully gives chase after the bird into a dark canyon, forgetting his mission. He suddenly finds himself staring into the face of the dreaded Aconcagua, and remembers the warnings of its violent downdrafts and sudden storms. He endures a frightening ordeal of lightning strikes, fierce winds, and torrential rain. The mail pouch slips from his wing, and while the narrator tells him to forget it and save himself, Pedro power dives in determination to catch the sack, finally retrieving it, but at a cost. He has used up most of his fuel, and now sputters and coughs in the desperate attempt to rise above the storm to safety. The scene fades as it appears Pedro is stalling, and being dragged back down, down, down into the clouds. At the airfield in Santiago, searchlights scan the skies for him, but find nothing, as Mama and Papa wait tearfully, believing their son lost. Just as the lights begin shutting down to give up the search, a small sputtering sound of an engine is heard. A light is turned back on, and follows the sound of multiple bounces upon the runway. Pedro is found, upside down on his back, but in one piece, and with the mail pouch safely brought in upon his wing. The camera closes in on the pouch’s contents, consisting of a single postcard, translating to “Having wonderful time. Wish you were here.” The narrator mutters, “Well, it might have been important…”, as Pedro happily wags his tail at completing his mission.

Pedro begins a long spiral ascent upwards to the entrance to a high mountain pass providing his flight route. He gets caught in a surprise downdraft at the pass’s entrance, but pulls out of it quickly like a veteran. His first trip through the pass is largely uneventful, although he gets a glimpse of Aconcagua from a distance, and tiptoes past it, concealed inside a small cloud. Spiraling down to Mendoza, he receives a mail pouch, which he carries on one wing. Hearing encouraging compliments from the film’s narrator about being ahead of schedule, Pedro begins showing off with some aerial acrobatics – then comes face to face with a buzzard, who gives him a little razz, then turns tail on him. Pedro playfully gives chase after the bird into a dark canyon, forgetting his mission. He suddenly finds himself staring into the face of the dreaded Aconcagua, and remembers the warnings of its violent downdrafts and sudden storms. He endures a frightening ordeal of lightning strikes, fierce winds, and torrential rain. The mail pouch slips from his wing, and while the narrator tells him to forget it and save himself, Pedro power dives in determination to catch the sack, finally retrieving it, but at a cost. He has used up most of his fuel, and now sputters and coughs in the desperate attempt to rise above the storm to safety. The scene fades as it appears Pedro is stalling, and being dragged back down, down, down into the clouds. At the airfield in Santiago, searchlights scan the skies for him, but find nothing, as Mama and Papa wait tearfully, believing their son lost. Just as the lights begin shutting down to give up the search, a small sputtering sound of an engine is heard. A light is turned back on, and follows the sound of multiple bounces upon the runway. Pedro is found, upside down on his back, but in one piece, and with the mail pouch safely brought in upon his wing. The camera closes in on the pouch’s contents, consisting of a single postcard, translating to “Having wonderful time. Wish you were here.” The narrator mutters, “Well, it might have been important…”, as Pedro happily wags his tail at completing his mission.

Pluto and the Armadillo (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 2/18/43 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.), receives honorable mention. A leftover which fell begind production schedule to meet the release date of “Saludos Amigos”, the film received release as a separate short subject shortly afterwards. Mickey and Pluto are tourists, stretching their legs on a flight stopover in Belem, Brasil. Their plane curiously includes a plug for a genuine airline, bearing markings for “PAA” – Pan American Airways, a leader in international flights, who was also responsible for the line of China Clippers we have discussed before in these articles. “Pan Am”, as it became frequently abbreviated, continued in existence until bankruptcy in 1989, when its remaining routes were purchased by Delta. Plotline involves Mickey tossing an oddly-spotted ball for Pluto to chase, which rolls into the underbrush alongside the airfield. The ball is a dead ringer for the rolled-up form of a local armadillo, also surprised by the ball rolling into its domain, who curls up in protective fashion. Pluto can’t tell the difference between his own ball and the armadillo’s shell, and a comedy of mistaken identities ensues, until Pluto gradually discovers the little character inside, and becomes fascinated by him, forming a friendship. The 15 minute stopover ends, and the tower calls for passengers to re-board. Mickey, in his haste, grabs Pluto, but the wrong “ball”, and brings the armadillo aboard, for a surprise reveal on the trip home, as the plane flies off into the sunset.

Pluto and the Armadillo (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 2/18/43 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.), receives honorable mention. A leftover which fell begind production schedule to meet the release date of “Saludos Amigos”, the film received release as a separate short subject shortly afterwards. Mickey and Pluto are tourists, stretching their legs on a flight stopover in Belem, Brasil. Their plane curiously includes a plug for a genuine airline, bearing markings for “PAA” – Pan American Airways, a leader in international flights, who was also responsible for the line of China Clippers we have discussed before in these articles. “Pan Am”, as it became frequently abbreviated, continued in existence until bankruptcy in 1989, when its remaining routes were purchased by Delta. Plotline involves Mickey tossing an oddly-spotted ball for Pluto to chase, which rolls into the underbrush alongside the airfield. The ball is a dead ringer for the rolled-up form of a local armadillo, also surprised by the ball rolling into its domain, who curls up in protective fashion. Pluto can’t tell the difference between his own ball and the armadillo’s shell, and a comedy of mistaken identities ensues, until Pluto gradually discovers the little character inside, and becomes fascinated by him, forming a friendship. The 15 minute stopover ends, and the tower calls for passengers to re-board. Mickey, in his haste, grabs Pluto, but the wrong “ball”, and brings the armadillo aboard, for a surprise reveal on the trip home, as the plane flies off into the sunset.

The Flying Jalopy (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 3/12/43 – Dick Lundy, dir.) – Though audiences of 1943 didn’t know it, they were witnessing another sort-of landmark in this cartoon – the birth, so to speak, of a recurring villain who would become a favorite foil for a studio’s main breadwinning character – except that character was working at a rival animation house! Dick Lundy’s directorial career would span three studios – Walt Disney, Walter Lantz, and MGM. In this film during his tenure at Disney, he introduces a notable one-shot bad boy – a fast-talking salesman/flim-flam artist who can charm the birds from the trees, but has murder and larceny on his mimd. The character is one Ben Buzzard – a slick-as-a-whistle con man with battered silk hat and walking cane who presides over an establishment selling wrecked planes (except the word “wrecked” is crossed off of the lot’s sign, replaced by the word “used”). Donald Duck comes along with a wallet of cash, doing a little window shopping. Ben sees Donald’s wallet as gold at the end of a rainbow, and quickly steers the duck to an old monoplane, its tire popping a bubble in its innertube, and going flat even as it stands in place on the lot. Ben states that Donald can have the plane for absolutely no down payment, and helps Donald into the cockpit seat (while at the same time snapping back into place the tail and one of the wings which he has knocked off in the process). “A little matter of insurance”, he reminds Donald, handing him a blank policy of flight insurance to sign, paying benefit in case of accident. Donald signs his name on the dotted line, not noticing that Ben has the paper folded. When Ben takes back the policy certificate, he reveals the fold to the audience in secrecy, and shows off the unseen remainder of the page, in which the line on which Donald has signed authorizes payment to be made to Ben Buzzard as the beneficiary. (If this plot point sounds familiar to any fans of Woody Woodpecker, it’s not a surprise – for this is the same basic idea Lundy would use again upon moving to the Walter Lantz studios, in the film “Wet Blanket Policy”, to introduce to that studio’s stable of characters his newest villain creation – the better known and well-remembered Buzz Buzzard! With the exception of a new voice with a Brooklynese accent, and a five-o’clock shadow used on Buzz chin for the early Lanyz installments, Buzz in essentially a retreaded Ben Buzzard – such that Disney had the opportunity to cash in on the character first, but never recognized the potential of this snake-oil salesman for recurring roles, and never exploited the character in any subsequent film. Disney’s oversight was Lantz’s gain, and for the second time in his career, Lantz would cash in upon a former Disney property (the first being Oswald the Rabbit, and a third being the brief acquisition of Fatso Bear, the direct descendant of Humphrey Bear, in the hands of director Jack Hannah when he left the Disney studio.)

The Flying Jalopy (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 3/12/43 – Dick Lundy, dir.) – Though audiences of 1943 didn’t know it, they were witnessing another sort-of landmark in this cartoon – the birth, so to speak, of a recurring villain who would become a favorite foil for a studio’s main breadwinning character – except that character was working at a rival animation house! Dick Lundy’s directorial career would span three studios – Walt Disney, Walter Lantz, and MGM. In this film during his tenure at Disney, he introduces a notable one-shot bad boy – a fast-talking salesman/flim-flam artist who can charm the birds from the trees, but has murder and larceny on his mimd. The character is one Ben Buzzard – a slick-as-a-whistle con man with battered silk hat and walking cane who presides over an establishment selling wrecked planes (except the word “wrecked” is crossed off of the lot’s sign, replaced by the word “used”). Donald Duck comes along with a wallet of cash, doing a little window shopping. Ben sees Donald’s wallet as gold at the end of a rainbow, and quickly steers the duck to an old monoplane, its tire popping a bubble in its innertube, and going flat even as it stands in place on the lot. Ben states that Donald can have the plane for absolutely no down payment, and helps Donald into the cockpit seat (while at the same time snapping back into place the tail and one of the wings which he has knocked off in the process). “A little matter of insurance”, he reminds Donald, handing him a blank policy of flight insurance to sign, paying benefit in case of accident. Donald signs his name on the dotted line, not noticing that Ben has the paper folded. When Ben takes back the policy certificate, he reveals the fold to the audience in secrecy, and shows off the unseen remainder of the page, in which the line on which Donald has signed authorizes payment to be made to Ben Buzzard as the beneficiary. (If this plot point sounds familiar to any fans of Woody Woodpecker, it’s not a surprise – for this is the same basic idea Lundy would use again upon moving to the Walter Lantz studios, in the film “Wet Blanket Policy”, to introduce to that studio’s stable of characters his newest villain creation – the better known and well-remembered Buzz Buzzard! With the exception of a new voice with a Brooklynese accent, and a five-o’clock shadow used on Buzz chin for the early Lanyz installments, Buzz in essentially a retreaded Ben Buzzard – such that Disney had the opportunity to cash in on the character first, but never recognized the potential of this snake-oil salesman for recurring roles, and never exploited the character in any subsequent film. Disney’s oversight was Lantz’s gain, and for the second time in his career, Lantz would cash in upon a former Disney property (the first being Oswald the Rabbit, and a third being the brief acquisition of Fatso Bear, the direct descendant of Humphrey Bear, in the hands of director Jack Hannah when he left the Disney studio.)

Ben starts things off by spinning the propeller to start the engine, and yanking off a good section of one propeller blade in the process. As the plane bounces and sputters with motor knock in attempt to gain flight speed, Ben turns the craft’s tail to direct it straight into a box canyon. The plane begins to move, and Donald quickly realizes he is running out of room. He yanks back on the stick, and the plane shifts into an abrupt 90 degree turn straight up, just shy of the rocks. Its engine still knocking, the plane stalls in mid-air just short of clearing the upper canton wall, and Donald has to physically pull the drooping tail upwards to get it to clear the obstacle. Ben, in typical villain form, mumbles “Curses”, at this development – then proves he is not a buzzard for nothing, by resorting to his own natural flying abilities and taking wing into the skies to follow Donald. (It is never explained in the series why another bird should be able to fly naturally, while Donald, also a bird, is always depicted as flightless. As he is a white duck, maybe he’s been over-domesticated, unlike his wilder black cousin Daffy.) Flying above Donald’s head, Ben extends a friendly greeting. “Hi, Ace! Say, you’re good.” Donald beams a broad smile. For “fun”, Ben suggests a game of follow the leader. “I’ll lead”, he suggests. Ben proceeds to fly a graceful vertical loop around a cloud. Donald follows, but Ben knows the plane can’t withstand the forces of such maneuver, and both wings rip off while Donald is climbing. Donald and the fuselage complete the loop, while the wings remain below. Coming full circle, the fuselage luckily travels between the drifting wings, and panicky Donald grabs hold of them and snaps them back into place to regain control. Donald pulls out of the dive only a few feet above the ground, with such force that he nearly “blacks out”, and uproots three trees on the ground in passing. Ben is getting frustrated, and pulls up a cloud as a chair to sit and think out his next move. He spots a pair of rocky peaks, with a very narrow gap between them, too small for the plane’s wingspan. Diving into the cloud, Ben flaps his wings, and physically gathers up more clouds to form a ring around the mountain peaks, obstructing their view. Then, he beckons to Donald for more of the “follow the leader” game. Gullible Donald once again falls for the trap, while Ben, with skulls visible in his eyes, tells the audience “He’ll never make it!” As Donald gets closer to the peaks, the clouds diminish, so that he sees just in time the obstacle ahead. Borrowing from Woody Woodpecker, Donald tips the plane sideways, squeaking the plane’s wings through the narrow opening vertically to let him pass through. “You dirty cheat!” shouts Ben.

Ben starts things off by spinning the propeller to start the engine, and yanking off a good section of one propeller blade in the process. As the plane bounces and sputters with motor knock in attempt to gain flight speed, Ben turns the craft’s tail to direct it straight into a box canyon. The plane begins to move, and Donald quickly realizes he is running out of room. He yanks back on the stick, and the plane shifts into an abrupt 90 degree turn straight up, just shy of the rocks. Its engine still knocking, the plane stalls in mid-air just short of clearing the upper canton wall, and Donald has to physically pull the drooping tail upwards to get it to clear the obstacle. Ben, in typical villain form, mumbles “Curses”, at this development – then proves he is not a buzzard for nothing, by resorting to his own natural flying abilities and taking wing into the skies to follow Donald. (It is never explained in the series why another bird should be able to fly naturally, while Donald, also a bird, is always depicted as flightless. As he is a white duck, maybe he’s been over-domesticated, unlike his wilder black cousin Daffy.) Flying above Donald’s head, Ben extends a friendly greeting. “Hi, Ace! Say, you’re good.” Donald beams a broad smile. For “fun”, Ben suggests a game of follow the leader. “I’ll lead”, he suggests. Ben proceeds to fly a graceful vertical loop around a cloud. Donald follows, but Ben knows the plane can’t withstand the forces of such maneuver, and both wings rip off while Donald is climbing. Donald and the fuselage complete the loop, while the wings remain below. Coming full circle, the fuselage luckily travels between the drifting wings, and panicky Donald grabs hold of them and snaps them back into place to regain control. Donald pulls out of the dive only a few feet above the ground, with such force that he nearly “blacks out”, and uproots three trees on the ground in passing. Ben is getting frustrated, and pulls up a cloud as a chair to sit and think out his next move. He spots a pair of rocky peaks, with a very narrow gap between them, too small for the plane’s wingspan. Diving into the cloud, Ben flaps his wings, and physically gathers up more clouds to form a ring around the mountain peaks, obstructing their view. Then, he beckons to Donald for more of the “follow the leader” game. Gullible Donald once again falls for the trap, while Ben, with skulls visible in his eyes, tells the audience “He’ll never make it!” As Donald gets closer to the peaks, the clouds diminish, so that he sees just in time the obstacle ahead. Borrowing from Woody Woodpecker, Donald tips the plane sideways, squeaking the plane’s wings through the narrow opening vertically to let him pass through. “You dirty cheat!” shouts Ben.

No more playing around. Time to get lethal. Ben soars upwards, landing on the tail of Donald’s plane. He begins yanking at the rudder, jostling the control stick from Donald’s hands and hitting him repeatedly in the face with it. Donald now becomes wise that Ben means him no good, and grabs the stick, shaking it back and forth to pummel Ben off the tail. No sooner is Ben our of sight, than Donald finds the blade of a long saw emerging upwards and downwards from the fuselage, in a circular path around his pilot’s seat. Ben is under the plane’s belly, trying to saw Donald out of the picture. Donald pulls out a monkey wrench, and smacks Ben a good one, leaving the bird in a momentary daze. But Ben catches up again, and opens a panel below the plane’s rear fuselage, with a valve for clearing the gasoline tank. He turns the valve handle wide open, and a stream of fuel begins pouring out of the plane, while Donald’s gas gauge drops at an alarming rate on the dashboard. Ben heightens the danger and quickens up the peril by lighting a match to the emerging stream of gasoline, which trails the plane like the fuse of a powder keg. Donald spots it, clambers to the plane’s tail, and trues to put out the flame by fanning it with his hat. He only succeeds in catching his hat on fire, charring it to ashes. He then produces a scissor, and attempts to cut away portions of the fuel trail to leave the flame behind. But the fire catches up, melting Donald’s scissor blades into a welded mess. All Donald can do is try to outrun the fire, and he revs the motor to top speed. Ben finds himself in the way, and is pursued through a cloud by the plane’s prop, which carves his tail feathers into a bald stub. The plane reverses course, and darts under Ben again. Ben drifts downward from a narrow miss by the plane, forgetting the plane’s flaming fuel trail, and sits right upon the fire. With a shout of pain, he rockets past the plane, just as Donald realizes his own race is about over, the flames now only inches from the fuel valve. Donald leaps from the cockpit, grabbing hold of the fleeing Ben. As the two of them look at each other, both anticipate what is about to happen to the plane below. They cover their ears in an unusual way – each sets one ear to the other’s head, then plugs their opposite ear with one wing, as the aircraft explodes. Random parts rain through the skies, and Donald, Ben, and the plane’s remains fall through a cloud. When they emerge below, Ben has become bodily wedged into the remains of the fuselage and cockpit seat of Donald’s plane, his wings sticking out the sides in place of the plane’s own. Donald, wearing Ben’s hat and carrying Ben’s walking cane, lands in the pilot’s seat. Finding that Ben himself makes a rather sporty model of aircraft, Donald bats Ben on the head with the cane, and demands, “Contact!” With some consternation, Ben obliges, verbally replicating motor sounds, and glides through the skies with Donald aboard, while the Duck laughs heartily for the iris out.

No more playing around. Time to get lethal. Ben soars upwards, landing on the tail of Donald’s plane. He begins yanking at the rudder, jostling the control stick from Donald’s hands and hitting him repeatedly in the face with it. Donald now becomes wise that Ben means him no good, and grabs the stick, shaking it back and forth to pummel Ben off the tail. No sooner is Ben our of sight, than Donald finds the blade of a long saw emerging upwards and downwards from the fuselage, in a circular path around his pilot’s seat. Ben is under the plane’s belly, trying to saw Donald out of the picture. Donald pulls out a monkey wrench, and smacks Ben a good one, leaving the bird in a momentary daze. But Ben catches up again, and opens a panel below the plane’s rear fuselage, with a valve for clearing the gasoline tank. He turns the valve handle wide open, and a stream of fuel begins pouring out of the plane, while Donald’s gas gauge drops at an alarming rate on the dashboard. Ben heightens the danger and quickens up the peril by lighting a match to the emerging stream of gasoline, which trails the plane like the fuse of a powder keg. Donald spots it, clambers to the plane’s tail, and trues to put out the flame by fanning it with his hat. He only succeeds in catching his hat on fire, charring it to ashes. He then produces a scissor, and attempts to cut away portions of the fuel trail to leave the flame behind. But the fire catches up, melting Donald’s scissor blades into a welded mess. All Donald can do is try to outrun the fire, and he revs the motor to top speed. Ben finds himself in the way, and is pursued through a cloud by the plane’s prop, which carves his tail feathers into a bald stub. The plane reverses course, and darts under Ben again. Ben drifts downward from a narrow miss by the plane, forgetting the plane’s flaming fuel trail, and sits right upon the fire. With a shout of pain, he rockets past the plane, just as Donald realizes his own race is about over, the flames now only inches from the fuel valve. Donald leaps from the cockpit, grabbing hold of the fleeing Ben. As the two of them look at each other, both anticipate what is about to happen to the plane below. They cover their ears in an unusual way – each sets one ear to the other’s head, then plugs their opposite ear with one wing, as the aircraft explodes. Random parts rain through the skies, and Donald, Ben, and the plane’s remains fall through a cloud. When they emerge below, Ben has become bodily wedged into the remains of the fuselage and cockpit seat of Donald’s plane, his wings sticking out the sides in place of the plane’s own. Donald, wearing Ben’s hat and carrying Ben’s walking cane, lands in the pilot’s seat. Finding that Ben himself makes a rather sporty model of aircraft, Donald bats Ben on the head with the cane, and demands, “Contact!” With some consternation, Ben obliges, verbally replicating motor sounds, and glides through the skies with Donald aboard, while the Duck laughs heartily for the iris out.

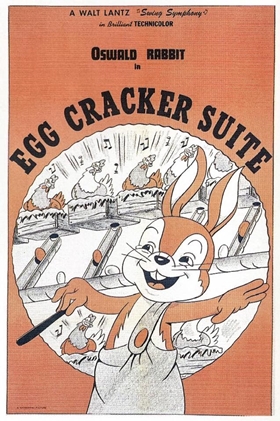

Just in time for the Easter season, we close with The Egg-Cracker Suite (Lantz/Universal, Oswald Rabbit, 3/22/43 – Ben Hardaway/Emery Hawkins, dir.) – A final fling for Oswald Rabbit, in redesigned form following his remodeling in “Happy Scouts” and in Walter Lantz New Funnies comics. This would mark his first, and nearly last, appearance in full Technicolor. He would only be seen again as a walk-on among attendees of a barn dance in “The Woody Woodpecker Polka”, and in an odd theatrical automotive commercial in the late 40‘s or early 50’s, pairing him with Andy Panda.

Just in time for the Easter season, we close with The Egg-Cracker Suite (Lantz/Universal, Oswald Rabbit, 3/22/43 – Ben Hardaway/Emery Hawkins, dir.) – A final fling for Oswald Rabbit, in redesigned form following his remodeling in “Happy Scouts” and in Walter Lantz New Funnies comics. This would mark his first, and nearly last, appearance in full Technicolor. He would only be seen again as a walk-on among attendees of a barn dance in “The Woody Woodpecker Polka”, and in an odd theatrical automotive commercial in the late 40‘s or early 50’s, pairing him with Andy Panda.

The film is a visually-lavish update on Disney’s Funny Little Bunnies (1934), tracking the process of production of the annual Easter baskets by a community of Easter bunnies, with Oswald now in charge. Similar to the Disney original, Oswald conducts a musical session with a flock of hens, timing their production of the eggs needed to supply the baskets. However, Oswald has one unusual addition to the chicken coop – an egg-laying ostrich, who wows the other fowl with one mammoth egg as the grand finale of the concert. Bunnies wait at the bottom of a chute to carry each egg to the hard-boiler for production. The last bunny in line is the smallest of the community, and receives a shock as he also receives the biggest of eggs, which bowls him over from the chute. He encounters various difficulties along the production line, nearly unable to push the giant egg into the egg dye pot, until it rolls in by itself, splashing the bunny with dye. The completed baskets are carted to the Bunnyville airport, where a squadron of bombers awaits as the baskets are loaded aboard. The little rabbit has finally completed the dyeing and decorating process of his egg, and calls for the other bunnies to wait for him, as he races to the airfield, carrying the egg on his shoulders. Suddenly, to his surprise, the shell cracks, and it seems the boiling process was none too thorough – instead providing only enough heat to hatch a baby ostrich! The ostrich stares eye to eye at the little rabbit, then takes hold of the rabbit’s ears, and tosses him into the plane. The planes take off, and high in the sky, open their bomb bay doors. Out fall all the Easter baskets, for a new-fangled method of delivery, as their ribbons balloon out to serve as parachutes. Inside one basket rides the little rabbit, whose basket is late in opening, but finally slows from the ribbon’s effect at the last minute to float him safely down. The rabbit sulks a bit at his botched delivery job, realizing he himself will now be the delivery, but brightens enough to give a happy holiday wave to the camera as the scene fades out,

Some super-powered doings, and an Academy Award winner, next time.