How a 'pot-smoking, acid-gobbling smart-arse’ became the producer behind some of Australia’s greatest music

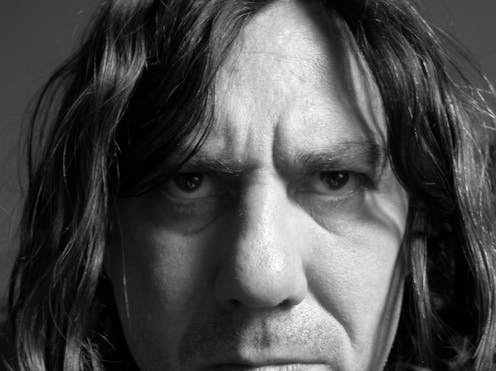

Maybe he’s someone only musicians know about. Which is criminal. Or maybe this excellent memoir by engineer and producer Tony Cohen, who died in 2017, will fling him into the spotlight. Which is appropriate.

Cohen, who was mostly Melbourne-based, made an astonishing contribution to Australian recorded music in the 70s and 80s.

It seems glib to reduce a busy creative life to a list, but these highlights are the main roads on the map of our culture through those years: Lobby Loyde, The Ferrets, The Boys Next Door, Laughing Clowns, Models, The Reels, The Birthday Party, The Go-Betweens, Hunters and Collectors, Cold Chisel, The Beasts of Bourbon, The Saints, Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, Tex, Don and Charlie, The Cruel Sea, Tiddas …

Review: Half Deaf, Completely Mad: The Chaotic Genius of Australia’s Most Legendary Producer - Tony Cohen, John Olson (Black Inc)

Half Deaf, Completely Mad is co-written with John Olson. Olson, as Cohen did, works in studios as an engineer (they worked together on Augie March’s Bootikins), but also as an archivist and oral historian.

Olson’s role in this book is essential to its success. Cohen had started the beginnings of a book in 2012, tapping out tales on his laptop. And then Olson started interviewing Cohen and many of the people who had worked with him.

But Olson made the wise decision to just let Cohen’s voice tell the story in this book, and it is clear and conversational off the page; he is both funny and irreverent. Cohen’s are stories of glorious inventiveness and dire indulgence from someone with a (mostly) keen memory. The gist of the stories was pure, even if the dates might have needed a bit of research on Olson’s part.

Ken Gormley, Cruel Sea bass player, commented after Tony’s death:

He was so fucking funny and sweet, complex, troubled, super intelligent, irreverent, totally maddening and just brilliant.

Cohen’s life unfolds through the book as a long, chronological series of vignettes, separated by his handwritten initials TC and punctuated with exhortations to listen to songs that illustrate the tales – making it clear that the context of this life is music, and you’d better go and listen closely to these songs! Hear all the stuff he’s talking about: the sound and the songs; the people and the times.

‘Turn it up a bit more!’

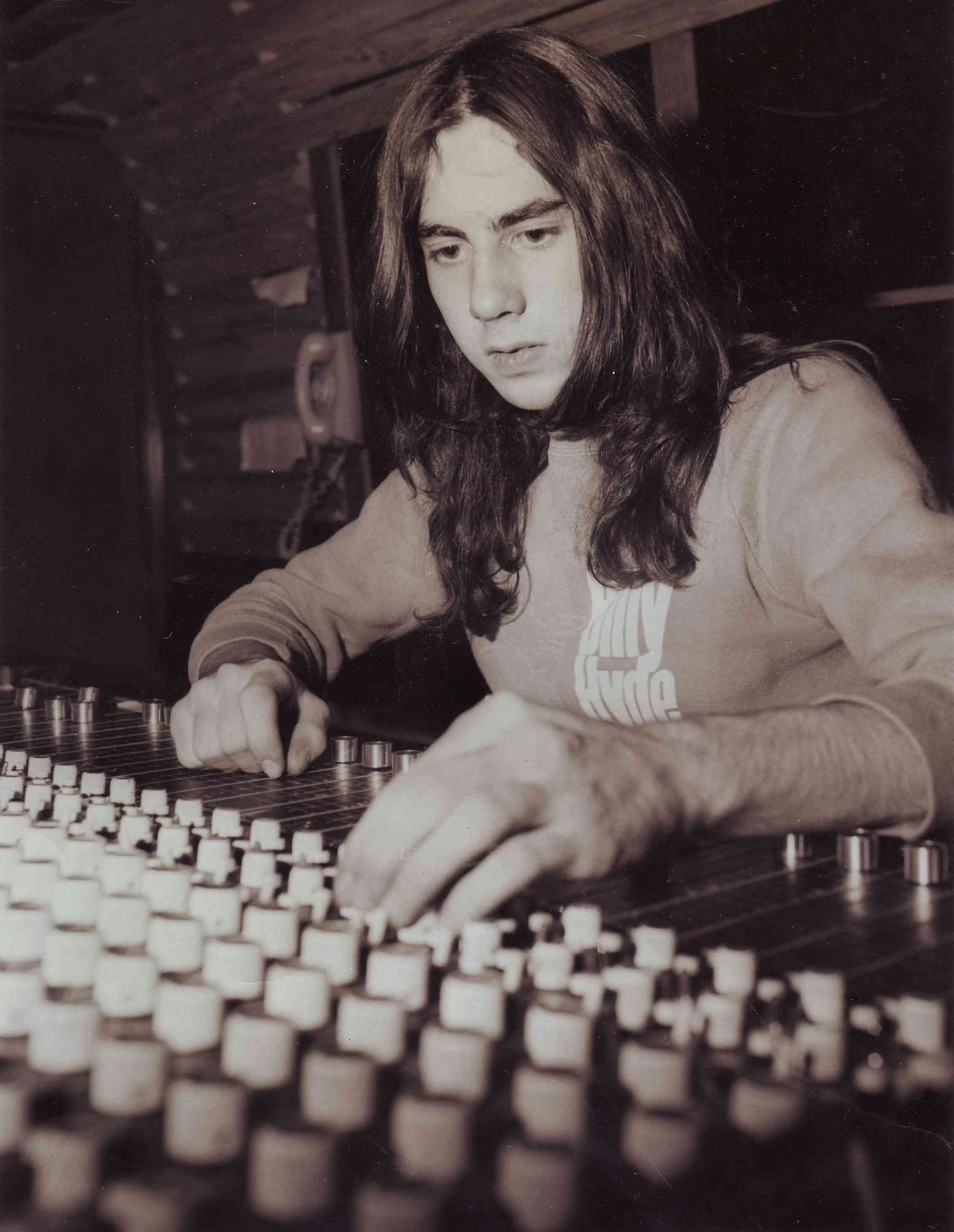

Cohen grew up in the Melbourne suburb of Mentone in the 1960s, playing covers in garage bands, but the stories really start when, in 1973, he was introduced to Bill Armstrong, owner of Armstrong Studios, Melbourne’s centre of music recording.

Working as an assistant, cleaning toilets and getting coffees, he was 15 and he had a job! In the first week he was paid $17 – “I was so young I spent it on lollies. And hash.” These were learning years, as he slowly brought bands into the studio in the quiet hours, getting better at this obscure craft, and developing an ego:

I was up myself: a pot-smoking, acid-gobbling smart-arse who thought he knew it all.

This time at Armstrong’s was informative, not just in learning what to do, but what not to do. Olson has allowed this part of the story to breathe deeply.

“He was really keen to talk about Armstrong’s and early recording,” Olson told me in a recent interview, “because they had taught him so much. And he talks a bit about Molly [Meldrum], which people will probably be surprised to read.”

Cohen’s regard for Molly Meldrum is clear. Molly was a ground-breaking music producer in those magic years from the late 60s into the 70s, as youth culture swung into revolutionary mode. As Cohen says in the book:

He taught me so much, though he wasn’t meaning to […] Molly’s secret? Exaggeration […] Turn things up louder than is considered tasteful. It might sound like you should pull it back, but resist that temptation. Turn it up a bit more!

But the core of Cohen’s reputation is anchored in the work he did with The Boys Next Door, The Birthday Party and The Bad Seeds. He met Nick Cave, Mick Harvey and the boys in 1979, and engineered and mixed their first cluster of albums, peaking with Junkyard in 1981.

Everything culminated in a trashy, nasty-sounding recording. Well, that’s what they wanted.

This idea – helping the musicians to get what they want – is at the heart of Cohen’s success as an engineer and producer. Studio engineers know the gear and the rooms they work in intimately, while keeping sessions running smoothly; producers are all about getting the band’s ideas to the right audience, often keeping record companies happy. Cohen didn’t have a “sound” like some producers do, he saw his job as capturing the sound of the band, as transforming ideas into reality.

A strange, scrambled method

According to Olson,

Mick Harvey said to me that they felt that there was no one else at that time. That [Tony] WAS the person to work with, because he would be hands off and let them explore things and not say no […] Tony was prepared to throw himself into the whole thing and see where it went.“

I also spoke with Laughing Clowns drummer Jeffrey Wegener about recording with Cohen at Richmond Recorders in 1979 and he echoed this sentiment:

He was the only one. He was daring to do different things, and there was a bit of "Fuck you!” to what the normal music benchmarks were. He didn’t care that I wanted to tune my drums differently, it was all cool. Go!!

The training and workplace practices of studio engineers up to this point created that “no” mentality, and their way of working was quite removed from Cohen’s methods. Blixa Bargeld called him “The Anti-Producer”. Cohen wrote:

I’ve got a strange, scrambled way of working. I know how to use most pieces of equipment, but I don’t necessarily know what they do or why they do it.

He talks about rooms and equipment in the book, and how he records things – inevitably. Why Yamaha NS10 speakers work; the usefulness of Neumann U87, U89 or TLM170 microphones if you are recording Tex Perkins; the Lexicon 480L reverb unit. It feels natural. This is, after all, a book about a working life.

By the mid-70s, Cohen had become comfortable with drug-taking of all types and as the decades passed he developed addiction problems, and eventually chronic health issues. In 1984 he asked Roger Grierson, independent label head and band manager, to manage him. (“It didn’t last long and I tortured the poor man.”)

Grierson remembers, in his recently published memoir:

He was a brilliant human being and a lovely guy, funny and clever, and that meant everyone would forgive him his transgressions, which were many […] “I’m just going to clean my teeth” was a euphemism for “Going to score, back in a few days … maybe.”

Cohen doesn’t shy away from this part of his story.

Drugs played a big part in music, especially punk. I became so accustomed to drugs in the studio that they formed part of the equipment and I wouldn’t contemplate a session without consuming copious amounts. Junkyard is not just an experiment of sound, but of physical ability to cope with drugs.

In 1987, after recording and mixing a swathe of Australian music including Models, The Go-Betweens, The Reels, Pel Mel, The Johnnys, and X, and some time in London, Cohen moved to West Berlin. Recordings with These Immortal Souls and Crime and the City Solution followed, as well as a re-invigoration of the working relationship with Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds. West Berlin was, he writes, a turning point. “It wasn’t a business, everything was done purely on an artistic level.”

Back in Australia in 1988, and on methadone, over the next few years Cohen produced albums for The Cruel Sea, Beasts of Bourbon, Dave Graney, Mixed Relations, Tiddas and The Blackeyed Susans, and most importantly, met his partner till the end, Astrid Munday.

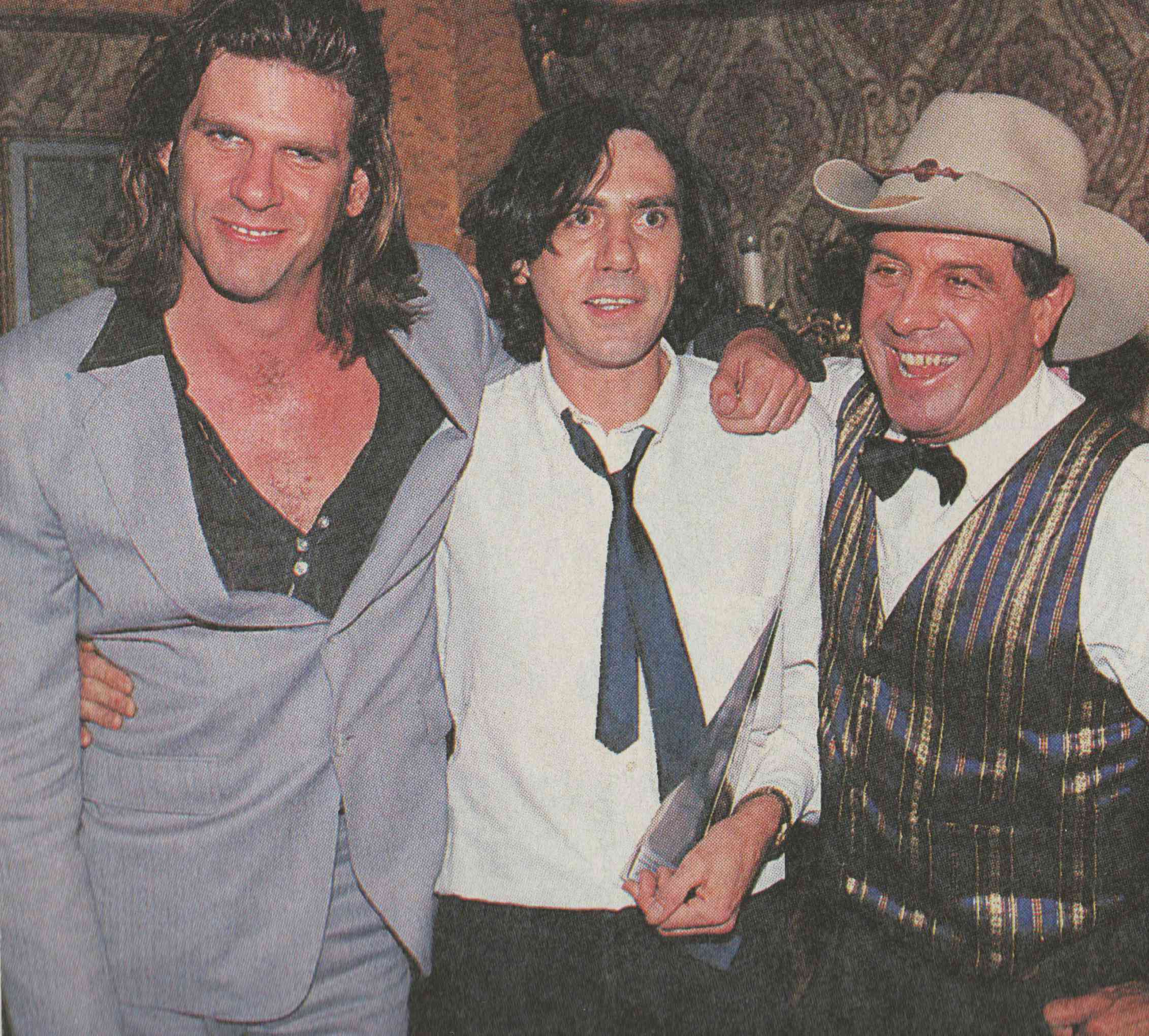

Cohen won Producer of the Year at the 1993 ARIA awards, saying, “this is an award I think I richly deserve”. But by 1995, with two ARIA wins, he was too ill with complications from diabetes to get up on stage.

Nick Cave posted on Facebook after hearing of Tony’s death:

Tony was pure chaos in the studio and like many geniuses a nightmare to work with. But you came back again and again because he was just so good, everything he did was so unique and bold and startling. He was a master at both what not to do in the studio and what to do in the studio. For example – don’t set fire to the studio, don’t sleep in the air-conditioning vents, don’t not show up to the sessions for days at a time, but conversely – do record music like your very life depended on it, do create sounds that no-one has ever heard before, do mix records with a courage that put every other producer in Australia to shame. He was also the funniest guy I have ever met […]

At the end of the book is a list of Cohen’s compadrés who have passed on, maybe 60 names, most of whom you will be familiar with. Tony was a sweet man, well-loved, and those relationships meant a lot to him.

“I get very upset when I lose another but I dream a lot,” he says. “It’s always a jumble of those who are with us and those who are gone, and I wake up happy because I feel like I’ve been in touch with them again.”

Hopefully he visits his loved ones in their dreams. And he will always be in touch with us through the music he helped create, and through the words in this wonderful, lively, funny book about a working life in music.

John Willsteed does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.