How a Sensitivity Reader Gave Me a Clearer Picture of My Grandfather

A photo of my grandfather sat on my desk: he cradles me, a swaddled baby, in his arms. He wears a white dress shirt with a 70s-style collar and looks down at me with overwhelming tenderness. I was thinking about him, about anger, about what it meant that I could hear and he could not. Growing up he lived just a few houses down from me and we used to go fishing together, bobbing in the water in his peeling rowboat, spending hours in the peace of it. His death when I was seven hollowed me out, but the stories of him sustained me for years afterwards.

When I would wake from a nightmare, my mother would make me warm milk and calm me with stories not of princesses and dragons, but of my grandfather. He emerged a hero again and again, relatively unscathed by the oppression he faced his whole life long. I carried this ideal with me well into adulthood. But now, looking at this photo, I was beginning to wonder if I knew him at all. My peaceful mythology had recently been challenged by someone whom I had hired to do just that.

It was the early winter of 2020, and my book was moving into the late stages of production. A critical biography of Alexander Graham Bell, it focused on his troubling legacy for deaf people—a legacy my deaf grandparents and great aunts and uncles lived with. But I am a hearing person, and so I hired a deaf person as a sensitivity reader, someone to review the manuscript and point things out that I was likely not to notice: misrepresentations, microaggressions, missed opportunities. I knew there were things that I would miss because I am hearing, and I knew that someone from within the deaf community would have the experience and expertise to guide me. Most of my book was historical but the prologue and afterword delved into the way Bell’s legacy had shaped my own family. What I hadn’t really considered when I sent my manuscript to this stranger was that they would be offering feedback not only on my historical research and storytelling, but the way I understood my own past and my own family, especially my grandfather.

*

My grandfather was my hero my whole childhood—both before his death and afterwards. He was gentle, brave, patient. When I was about eight, my father asked me what was so special about him. “He never yelled,” I said. “And he always had time to play.”

But my grandfather had been shaped, I knew, by the legacy of Alexander Graham Bell. It was in part because of Bell’s work to suppress American Sign Language that my grandfather didn’t learn any language until he was in his twenties. As a child I knew this, and as an adult I also knew that language deprivation like this had irreversible consequences. But I’d been told that my grandfather was the rare exception: He was “okay.” I loved him with all my heart, could see no flaw in him, and so I accepted this story.

I was thinking about him, about anger, about what it meant that I could hear and he could not.My sensitivity reader saw it differently. They pointed out that it was a very hearing thing to do, to believe in the exceptionalism of a deaf individual like that. And worse, one who was calm, peaceful, beatific. As soon as they said it, I knew it was true. The person unscathed by such a deeply formative experience as language deprivation is a fantasy, a fantasy that hearing people rely on all the time in representations of deaf people. What could be better than a person who doesn’t seem to absorb the violence thrown at them, who instead becomes a keeper of other peoples’ stories, a blank slate, or a silent guide who serves only to support people with presumably more agency than they? I knew this trope well; what horrified me was the ways in which I had replicated it.

But more than just replicating, I began to wonder if the trope operated in me. I may have descended from deaf people, but I am hearing and I understand the world largely from a hearing perspective. Now I couldn’t look at these stories—these stories that made up my childhood mythology—without wondering what lurked beneath them. My reader had suggested that there might need to be more of a sense of anger surrounding my grandfather, but my memories and stories about my grandfather were devoid of such an emotion. Now I wondered: How much had we missed? What had been erased simply by the filter of hearing people passing down stories of him? And—I could barely even form this thought—what had my own hearing gaze erased?

I had not even thought to question my grandfather’s miraculously unscathed emergence from language deprivation; I never thought to ask about my grandfather’s rage. I hadn’t even thought of it. Now my mind kept spinning around this question: did my grandfather ever get angry? Surely he did.

I still needed help, and brought the question to a friend who grew up within the deaf community, and understood the issues in a way that hearing people can’t. She patiently suggested that not every person who faces oppression responds with anger, and that it’s pretty common to idolize your elders, that maybe my grandfather really just wasn’t an angry guy. But she also emphasized what my sensitivity reader said: a person who is language deprived is marked by that. No one escapes. Not even if they are a good person; not even if they are my grandfather.

I knew his tenderness and his playfulness, his love of the water, his slow steady rhythms. He was a good man.Now I thought of Sanjay Gulati, the clinical psychologist who gave a groundbreaking talk on language deprivation. His words rang out in a new way: “If you don’t have an L1, you have brain damage. It cannot be resolved.” I knew that there was a wide range of what that could mean for someone—for some people, that damage was severe, for others it was more subtle, but it always irreversibly changed a person. I knew all of this and yet still, somehow, I had never put that idea together with my grandfather.

*

I had begun to feel like I didn’t know my grandfather at all, but that wasn’t quite true. I did know him—not all of him, but parts of him. I knew his tenderness and his playfulness, his love of the water, his slow steady rhythms. He was a good man. And that’s what made the injustice of language deprivation so much worse. I began to wonder about the parts I didn’t know: the ways he was held back, how this played out both neurologically and beyond. I began to make room inside of myself to understand my grandfather more fully—not only his peace but the way he’d been scarred.

I wrote something new. I layered in my understanding of language deprivation and the insight that my deaf sensitivity reader provided, and brought that to bear on who he was. I worked to undo the erasure that had happened not only on the page, but in my own mind. I couldn’t resuscitate parts of him I never knew, and I didn’t know his anger, but I could assure that the injustices he faced were presented beside him. And maybe, with this new perspective, I could better honor his life as he lived it, not merely as I remembered it.

__________________________________

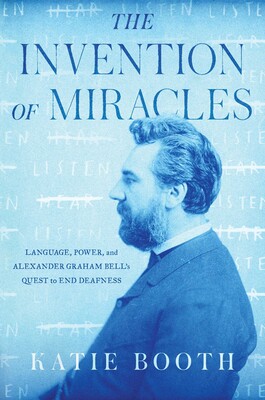

The Invention of Miracles: Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bell’s Quest to End Deafness by Katie Booth is available now from Simon and Schuster.