How Crafting Got Me Through the Worst 700 Days of My Life

Maybe we all, at some point, find ourselves in the middle of a life that we do not recognize. Or maybe it’s just me. You go along to get along, you fake it ’til you make it, you follow the steps as you understand them and then, one day, you are the roadrunner off the cliff, still sprinting, supported by nothing but your own conviction that this is what one does. And then you are falling.

Things weren’t perfect, of course, but I took pleasure in my life, my friends, my family, my giant precious neurotic angel-dog, Eleanor. I wrote things and went places and saw people. I pored through the aisles of Goodwill to find alarming tchotchkes to hide in my mother’s bathroom cabinet. I made happy, involuntary noises when eating prosciutto or burrata.

Then, one by one, my body dissolved, my mind dissolved, my relationships dissolved; the things that anchored me to life slowly faded.

Honestly, I had it coming. I had this ridiculous, picture-perfect five-year run that I knew was just absurd and would not last.

It started with my first book deal, which was akin to being struck by lightning.

I’d worked for years as a newspaper reporter, the only thing I’d ever wanted to do. Everything about being a reporter suited me—go out in the world, see everything, ask any questions you like with that little notebook in your hand lending legitimacy to your curiosity (also: nosiness). I covered events, music, and nightlife, which, in my town meant garage bands, the Oregon State Fair, and alpaca farms during baby alpaca season. I wanted to do that forever, but I couldn’t, because the journalism industry I was deeply in love with was dissolving in real time.

So I began to think about what else I could do. I applied for jobs like assistant public information officer at the Department of Sewerage and Waterworks. It didn’t have the same ring as “newspaper reporter,” but, hey—it had health insurance and perhaps would mean no gutting layoffs every six months.

Then I had an idea for a book full of the practical parts of being a grown-up (getting renters’ insurance! asking for a raise! keeping counters clean, which I still never do!). To tie it all together, I made up a really irksome but memorable word that is now mocked on podcasts, is emblazoned on hats at Target, and somehow came to embody society’s ideas about a whole generation of Millennials… when really all I was trying to do was share a few handy tips and maybe make rent while local journalism burned around me. A few years later and voilà! I was the “Adulting” girl, an avatar of togetherness and competence, which, again, I truly never was.

I will take a moment to apologize for introducing the word adulting to the world, which annoyed me even as it came out of my mouth the first time. Now, almost ten years later, I see it on Instagram and ironic T-shirts and as titles of books that other people have written, and it’s still annoying. I don’t apologize for the book itself, which I maintain is quite good. The only thing inventing a word gets you is the fun of absolutely insisting to strangers in bars that yes, you made it up—“NO, SERIOUSLY, LOOK IT UP. IT’S ON KNOWYOURMEME.COM.”

I was good at gathering information and putting it together in a readable way; I was good at comforting people who are being too hard on themselves and are doing much better than they give themselves credit for. It was not blithe or dishonest. I acknowledged my own flaws and never pretended I was a perfect or even above-average adult.

But everyone thought I was! Somehow I became associated with this persona of perfection, an avatar of having one’s shit together that was, decidedly, not me. This was a very effective way to tee myself up for a lifetime of disappointing others with my haplessness.

I will take a moment to apologize for introducing the word adulting to the world, which annoyed me even as it came out of my mouth the first time.So, the briefest recap: I got discovered out of nowhere, sold a book at auction that became a best seller, spoke at NASA, had a beautiful wedding, was the subject of a very kind New York Times profile, and became known as an expert on how to be an adult and how to be gracious… even though I’m not very good at either of those things.

For the first time in my life, I didn’t have to check my bank account before I paid my car insurance. I put that shit on auto-pay! It was a charmed life, although as a lifelong depressive, this didn’t prevent me from sometimes thinking it would be pretty convenient if a semi smashed into me on my way home.

Think of some achievement or honor or item or person that you thought was what was standing between you and happiness. When you got it, did you find yourself whole and happy? Or temporarily satisfied but then hungry for the next thing?

I was finding success hollow. It is amazing, yes, and it was fun in the moment and made for an impressive bio. But it doesn’t—and can’t—sustain you. The quality of your relationships, the skill of building and keeping contentment, and your ability to sit with pain and not squirm away from it is what will actually keep you going after that first flush of happiness. Not that I understood any of this back then. Creating a life on the memory of something that, even in the moment, you didn’t think you deserved is not a stable foundation.

And then, the foundation crumbled further. I got a divorce, a certain someone was elected president, my antidepressant stopped working, my body started breaking, and my luck ran out. Life began to rapidly dissolve. All I had left to sustain me was the small, joyous triumph of making things. Like those little paper stars that took almost zero brainpower but somehow kept me moving, doing, creating during the moments when everything (and everyone) else abandoned me.

Crafting, in fact, got me through a pretty terrible 700 days. I was such a wretch during this period, I cannot even tell you. Things went from bad to worse, from worse to atrocious, and from atrocious to unthinkable, at which point the whole thing just became bleakly hilarious. Sadly, I was too depressed to appreciate jokes, even really good ones, like what my life had become.

I’ll tell you about most of them in here, but some highlights include:

• Breaking three of my four limbs in separate and unrelated incidents;

• Cat and grandmother deaths within a week of each other;

• What a therapist accurately billed as “catastrophic loss of chosen family”;

• Sinking into a deep depression that meant I wrote (and did) nothing for a year;

• Four days of in-patient mental health treatment, which I like to call my “rest cure” because in my mind I am a fancy Victorian lady;

• A relationship’s irreparable breakdown within 36 hours of breaking my ankle;

• Dad-cancer; and

• Trump

As you can imagine, it was quite the time!

Seeking help and being open about what was going on was complicated by my career, which as noted consisted of giving helpful advice to people who feel sad and confused. I was—other people seemed to think—someone with ideas on how to live one’s best life, ideas that didn’t include lying listlessly on a dog-hair-covered couch watching Bob’s Burgers on repeat for months at a time.

“Didn’t you write a book on this?” someone says when I make any sort of error, which is often, as I’m a space cadet with poor short-term memory and executive function.

“You did! You did write a book on this!” Depression whispers malevolently. “Why in God’s name would anyone want to listen to you? How do you feel about your work and success being built upon a lie? Is that a caramel wrapper in your hair? What percentage, by weight, of this couch is dog hair? Why is the coffee table sticky? Were you thinking, when you bought this robe, that it was going to become your primary garment?”

This is all a very unhealthy and not-at-all-useful outlook that, with time and medication and effort, has improved somewhat.

I’m not alone in this. Well, I’m alone in the specifics of these 700 days, which, taken cumulatively, make it seem like I was cursed by a mean elf who specializes in plaguing middle-class white women in their 30s. But I’m not alone in some things.

My brain sometimes doesn’t make the right chemicals in the right amount—an ongoing problem for 20 years now. If it were, say, my kidney doing this, I could explain, “Hey! Got a wonky kidney, here, but I’m working on it. Please still invite me to stuff, and if I’m feeling good, I’ll be there!” and people would get it. Maybe they would also know that sometimes I am not present because I’m exhausted and/or scared, and that I didn’t text back because it felt like the equivalent of climbing a mountain, somehow. But it’s my brain, not my kidney, and so the very dull fact that it’s that organ improperly functioning becomes this huuuuuuge thing that I’m not allowed/too ashamed to talk about, even though it affects so much.

Creating a life on the memory of something that, even in the moment, you didn’t think you deserved is not a stable foundation.I so, so often feel like I am too much, exhausting even to myself, and doing everything in the wrong amount. Eating too much or too little, drinking too much or too little, or feeling things too much or too little.

It is so easy to feel lonely and adrift a lot of the time. This is going to be a weird digression, but please come with me: are you familiar with Caroline Manzo, formerly a Real Housewife of New Jersey? I think I am most jealous, of all the people in the world, of Caroline. She has this enormous clan of an extended family that is constantly gathering to eat thousands of dollars’ worth of meat together. She knows in her heart there is no better place in the world for her than Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, where she can sit and gaze proudly upon the world she has created.

More than anything, Caroline has certainty—about how life is and how life is supposed to be, about herself, and about her place in the universe. She is so tethered. It’s the same envy I feel for the very religious. They don’t have to question; they just know, and they have hundreds of other people who also know, and they’re all making something delicious for this Sunday’s potluck. The idea of this obedience and submission is chafing, but it sure does look nice. I wish I knew.

But honestly, in this case, I’m not sure how it could’ve been helped. A bunch of bad things happened one after another. Each time something bad happened, I withdrew from the world a little bit more and cared about my life a little bit less. It’s always been the case that sometimes I don’t feel like being alive, in the same way that I sometimes don’t feel like vacuuming my house or following through on happy-hour plans, but it had never been like this.

I had all kinds of resources at my disposal, and I still couldn’t get the help I needed. With great and extended effort, I finally found it, but I had to almost die for that to happen.

But before I had help-help, I had crafts. Crafting has always calmed me, made me feel better, and given my hands something to do so my brain can stop shrieking at me for one gosh darn second.

So in those 700 days, when I wasn’t able to work, leave my house, or function as a human, I crafted. I couldn’t write—I didn’t have anything to say, plus one doesn’t get much writing done when one is in bed 14 hours a day and catatonically watching MSNBC the other 10—but I could embroider, letter, teach myself block printing, cut out Bad Decision Shrinky Dink charm bracelets, make weird modular origami spheres, fold literally thousands of tiny stars, and, just for good measure, make those trivets out of plastic tube-shaped beads that you then iron to melt one side.

Crafting gives me a sense of accomplishment even when I feel like I can’t accomplish anything. Crafting is tangible proof that I can do something. To craft is to set things correct in tiny ways—to make this crease or that stitch or move that candle over a bit because it just looks better there—and I can almost always affect these changes in the universe. Crafting reminds me that my brain moving differently from other people’s brains is not all a bad thing.

Once, I was talking to (or, more accurately, crying on the phone with probably also) Carol, one of my mom’s best friends. Carol is an incredible artist and said something that made me feel so much better.

Tenderness, she said, is the price of being an artist. If you want to see and create things that other humans haven’t seen or created, that means you’re going to feel things a little bit more than others do. Those two parts of oneself cannot be divorced. The pain is both a feature and a bug.

If you think about it, it’s a little absurd that we get depressed, on an evolutionary level. Experiencing something that makes us 1) stop taking care of ourselves, 2) uninterested in sex, and 3) not eat properly because we’re too busy sleeping 20 hours a day doesn’t make a ton of evolutionary sense. But it’s so, so common—the number-one disability in the world—and something experienced by 30 to 50 percent of Americans at some point in their lives. So, the theory goes, it must do something.

Some theorize that depression is, in fact, an adaptation because the depressed are really, really good at dwelling on things. We have “depressive ruminations,” as Paul W. Andrews and J. Anderson Thomson Jr. put it, and “this thinking style is often highly analytical. They dwell on a complex problem, breaking it down into smaller components, which are considered one at a time.”

Because, they said, you’re not concerning yourself with things like other humans or basic hygiene, you can truly lean into solving whatever problem has swallowed you whole.

As someone who has always wanted a normie brain, this brings me comfort, in the same way learning that being a night owl doesn’t mean you’re a lazy dirtbag. It was evolutionarily useful to have a few humans who are wide awake at 1 a.m. to watch over things and, for whatever reason, it is useful for humanity to include depressed people who are great at dwelling on shit.

Crafting gives me a sense of accomplishment even when I feel like I can’t accomplish anything. Crafting is tangible proof that I can do something.These days, I’m feeling a lot better, thanks to lots of things that are part of that invisible work I mentioned, and also—perhaps mainly!—that I was finally able to access care. Most days, I feel pretty, or even really, good. I am not resentful that I have to leave my bed in the morning. I am happy when good things happen and sad when sad things happen, in reasonable amounts. As my therapist once pointed out, we don’t really have bad days, we have bad hours or moments.

But sometimes, ugly stuff bubbles up, so it’s nice that I can always just go make some crafts.

I cannot soothe my mind once and have it be done. I have not and will not permanently cure myself, in these pages or otherwise. No amount of peppy self-talk cures diabetes or hypertension, and I’m done pretending this is different. The brain is not special and apart; it’s cells, chemicals, and electricity that function (or don’t) for reasons that we will likely never fully understand.

There’s this temptation, in books about mental health (or heartbreak or addiction or any of the awful things that happen to us, although often with our enthusiastic help) to wrap everything up. I was drunk, but now I’m sober. I was depressed, but now I’m a sunny little person. That guy broke my heart, but the end of that relationship made space for my one true love, and so on.

It would be great (both narratively and, um, for my life) if there were some fixed finish line. And I had crossed it. And now I was Better, Forever, and You Could Be, Too. This is not the nature of anything, though. There is not a beginning, a middle, and an end. It’s a constant coaxing, reinforced with boundaries and medication. It is following good mental health hygiene—which is the real self-care, although it’s so, so boring! It is cultivating contentment rather than chasing happiness.

It is patiently asking myself the same questions: “Can you do anything about this right now? Should you do anything about this right now?” It is reciting the same reminders: “You sound really afraid right now, and that’s okay, but I don’t think there is anything actively dangerous happening.” It’s accepting that I will sometimes just feel afraid or sad or nothing at all, which is perhaps the worst of the three.

I cannot control the world, and I often cannot control my own mind, but dang it, I can make you an extremely thoughtful embroidered gift. No matter how far gone I feel, my fingers still know how to fold an eensy paper star or a cute snail. In this teeny arena, I will always find success, which reminds me of some important things.

I am resilient and scrappy as fuck, and you should never, ever bet against me. My crafts are not perfect or beautiful, but they are charming and I mean them. And sometimes, isn’t that all one can ask for?

________________________________________________

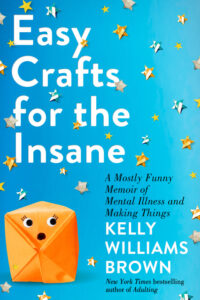

From Easy Crafts for the Insane: A Mostly Funny Memoir of Mental Illness and Making Things. Used with permission of G.P. Putnam’s Sons. Copyright © 2021 by Kelly Williams Brown.