How the Male Point of View Shapes the Narrative of The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby has long been one of my favorite novels. I loved it the first time I read it in high school. It was one of the first classics I was assigned to read that I truly enjoyed and that I found myself coming back to again and again in the years that followed. I admired not only Fitzgerald’s gorgeous prose but also the way the story unfolds as such a vivid slice of the Roaring 20s—the affairs and murders and the parties and the recklessness. But most of all, I was fascinated by the point of view Fitzgerald chose to narrate the story—Nick, the outsider.

As a writer myself, I’m always most interested in the idea of point of view. I love to consider the way the narrator of any story shapes that particular story. My stories are almost always told from the perspectives of women. In fact, I’ve been writing novels from the point of view of women in history for ten years. I’ve written fictional versions of real women (Margot Frank and Marie Curie), completely fictional women (female resistance fighters and musicians in World War II), and one prior reimagining of a literary character, in a young adult contemporary version of Jane Austen’s Emma.

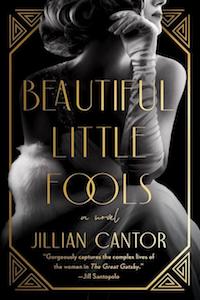

But my latest novel, Beautiful Little Fools, marks the first time that I’ve retold a predominately male story—a novel originally from a male writer with a male point of view character—as a story by and about and narrated by women. My novel is a feminist take on The Great Gatsby, told from the point of view of Daisy Buchanan, Jordan Baker, Myrtle Wilson, and Myrtle’s sister, Catherine.

In The Great Gatsby, Daisy Buchanan tells her cousin Nick that she’s upset upon learning her baby was a girl after she was born. “I hope she’ll be a fool,” Daisy says. “That’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.” This line became the starting point for my reimagining (and the inspiration for my title). Was this something a woman would truly believe at the time, I wondered? Or was it something a man would believe a woman would believe?

Even though some might argue The Great Gatsby is a (tragic) love story, I always wondered what the summer would look like from Daisy’s point of view.As a reader, I never believed Daisy was a fool, and I especially didn’t think her friend, Jordan Baker, was, but their characters aren’t explored enough in The Great Gatsby for us to truly know. The women in the original novel function mostly as side characters without agency, props without choices. And even though some might argue The Great Gatsby is a (tragic) love story, I always wondered what the summer would look like from Daisy’s point of view, and if she might feel altogether differently about Jay Gatsby than Nick thinks she does.

Writing this novel has gotten me thinking a lot, too, about women writers, women’s fiction, and “the classics.” The books I was assigned to read in high school and even in college as an English major were largely male point-of-view novels written by men, like The Great Gatsby. (I had to take a class taught through the women’s studies department in college to eventually find a syllabus filled with books by and about women.) I didn’t dislike these classic novels, I just longed for stories about women, too. As a writer, I’ve always aspired to write the kinds of novels that I myself want to read: stories about strong women. And my novels, Beautiful Little Fools included, are often classified as “women’s fiction.”

In Beautiful Little Fools I keep the timeline and events Fitzgerald set out in his original. Though my novel spans more time, it details the same events Fitzgerald himself created for these characters: Daisy and Jay meeting in Louisville, Daisy and Tom getting married and moving to France, then Chicago, Jordan playing on the golf tour, and eventually all of them ending up in Long Island in the summer of 1922 where Tom and Myrtle have an affair and Jay Gatsby is shot and killed. My plot is essentially Fitzgerald’s plot, my characters his characters. So what makes The Great Gatsby fiction (not “men’s fiction,” mind you) and Beautiful Little Fools women’s fiction?

It is true that many of my readers are women. But I do find myself sometimes resenting the implication of the women’s fiction label. It seems to be saying that men can’t be expected to want to read a book written and/or narrated by women. But I was always fascinated by Nick’s account of the summer of 1922 on Long Island in Fitzgerald’s novel. Why couldn’t a male reader be equally as fascinated by Daisy’s, Jordan’s, and Catherine’s in my novel?

At the beginning of Beautiful Little Fools, Catherine, Myrtle’s sister, moves to New York. She says after she steps off the train: “As of last month, women could even vote here. I could be someone in New York. Not someone’s wife. Someone.” When we first meet Jordan, she says she doesn’t want a man or a marriage, but a golf career.

And that is the crux of Beautiful Little Fools—my version of these women don’t want to be fools at all. They want autonomy. They want to be their own people, making their own way in the world, and they are the ones in control of the narrative this time around.

__________________________________

Beautiful Little Fools is available from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2022 by Jillian Cantor.