Making the Tricky Switch From Writing Adult Literature to Children’s

I never imagined I’d write a novel for children. Even when I was six or seven years old, a massive reader, and a kid who wanted to write novels one day, I saw myself writing for adults; only that seemed serious to me. I was a serious kid, and childhood, as far as I was concerned, was a temporary holding area until I reached my true home of adulthood, where I would organize my life the way I saw fit, understand things like politics and geography, and write fat books full of adult business: marriages and wars, most probably.

I did grow up to write novels for adults, not so much about marriages and wars, as it turned out, but rather shaped by all sorts of influences and experiences—and reading—I couldn’t have imagined at six or ten or even fifteen. One was about a loner living beneath the radar in New York City; another about a love triangle at an East Coast boarding school; a third, about childbirth. But between the first and second novels, I drafted a novel for children. I did it for National Novel Writing Month, which famously requires writing 50,000 words in 30 days. I’d always wanted to try it. To approach the daunting task, I chose a story for children, precisely because it was something I wasn’t invested in and didn’t see as important. I figured that would help me get out of my way and write freely and fast.

The wisp of a situation I decided on was that of a young girl whose mother decides she wants to adopt a refugee orphan from Vietnam. The Vietnam War was part of the anxious backdrop of my own childhood in the 1970s. On the evening news, there was frightening footage of soldiers pushing through jungle underbrush, explosions. I knew hardly anything about what was going on, but I took in the danger and the violence. When I was 12, the war ended after the U.S. withdrew its military and economic support and the South Vietnamese government collapsed. Now there were news stories about South Vietnamese families desperately trying to get to safety in rickety boats launched into the South China Sea and about orphaned children evacuated in planes. I had a younger brother, but I wondered what it would be like if we adopted an orphaned girl and I were to get a sister as well. For my NaNoWriMo novel, I gave my somewhat naive fantasy to the mother and made my protagonist a girl who was roughly my age when the Vietnam War ended.

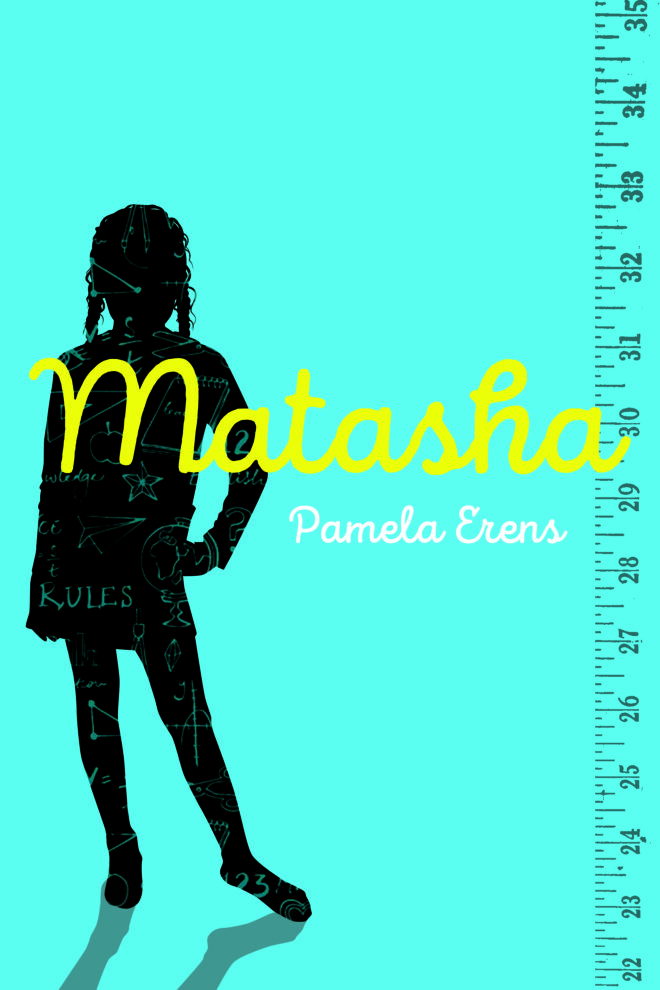

I wrote my 50,000 words, congratulated myself, slapped the name of my main character, Matasha, on the cover page as a title, and put the manuscript in my file cabinet, where, after a few months, I almost completely forgot about it. It had done what it was meant to do: scratch an itch to challenge myself and limber me up for my next (adult) writing project. I barely thought of it again for the next ten years.

I was a serious kid, and childhood, as far as I was concerned, was a temporary holding area until I reached my true home of adulthood.After I completed my third novel, Eleven Hours, I spent two years on a formally ambitious novel, eventually, painfully, abandoning it; it wasn’t working and I knew it. For the first time I didn’t have another idea in the queue that I felt fired up about. It was 2017 and I wanted to blame things on Trump, and maybe some of it was Trump: the way the world felt topsy-turvy and subjects that had seemed very important quite recently now felt potentially irrelevant. Or maybe it was just one of those natural fallow periods that writers and artists have to contend with over the course of a creative life. In any case, I began a number of new writing projects, making little headway with any of them, and one day suddenly remembered I had in my file cabinet the draft of a novel for children.

I took it out and read it. I’d recalled it as clumsy, silly, rather pointless: an interesting exercise, not a potential book. In fact I saw that the manuscript had energy and charm. I had captured, in that quick drafting—likely exactly because it was so quick and circumvented my reflective and judgmental adult self—so much about what it had felt like to me to be a child. The way adults smirked when they spoke to you, thinking you were too young to understand. The fear of large incomprehensible realities (crime, death) and small idiosyncratic ones (needles, sidewalk grates). How easily other children could press on your vulnerabilities and make you feel unacceptable in some deep and terrible way. The helpless love for and dependency on parents combined with a growing frightening sense that they were not as in control of things as they’d once seemed.

My story, essentially, was that of an 11-year-old only child whose mother is searching for solutions to her sense of emptiness and restlessness—thus the Vietnamese adoption scheme. In addition, the protagonist faces the possibility of uncomfortable medical treatment (she’s not growing at a normal rate) and the baffling withdrawal of her best friend’s affections. Classmates consider her bookish enthusiasm show-offy. Here, braided together, were some of the same themes I’d addressed in my novels for adults: loneliness, humiliation, self-consciousness, the fear of pain. But also—and more so than in those earlier books—there was humor and delight, the inescapable buoyancy of childhood. I was finally in love with a writing project again.

My novel took on a child’s view of life, so I’d thought it somehow lesser.It struck me that by banishing my manuscript to the recesses of memory, considering it not worth my time, I’d condescended to it in the same way I had felt condescended to by grownups when young. My novel took on a child’s view of life, so I’d thought it somehow lesser. And this despite my deep love for the middle grade novels I’d read to myself and then again later to my children, with enormous enjoyment, in their own middle grade years. Perhaps it had taken a decade to gain the psychological perspective and self-trust that I needed to embrace childhood material, to give it its full due.

While revising Matasha—adding and dropping scenes, fashioning a missing ending—I kept by me, as I’ve kept for all my novels, one or two particular books that serve as tutelary spirits, books whose voice and vibe I aspire to reproduce in my own way. For Matasha, these were Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy and Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding. The latter is not a book for children, although it is about a 12-year-old. It’s dreamy, intense, full of the panic and desire that a child on the brink of adolescence experiences. Harriet the Spy is gleefully anarchic and wise to the absurdity—even grotesqueness—of life, and particularly of grownups. I wanted the feel of both in my own book. I reread them over and over as I knit together my revision, working nearly as quickly on it as I had on the first draft, wanting to re-access its spontaneity and pleasure.

Like The Member of the Wedding and Harriet the Spy, Matasha was in third person—something not typical of contemporary middle grade novels. I suppose that I’d intuitively gravitated to that point of view because I wanted a bit of distance from my main character; I wanted to watch her rather than be her. Probably another reason was the subliminal imprint of the adored books of my own tween years. A Wrinkle in Time. The Phantom Tollbooth. The Wizard of Oz. Johnny Tremain. The Hobbit. These novels, all in third person, had a mild detachment about them, a wry adult sensibility that lurked behind the childhood story. That sensibility provided an extra layer of richness and gave the child me a taste of what an informed, benevolent adult perspective might feel like.

For the most part, these books also lacked easy epiphanies, the kinds of endings that drove me crazy even as a kid. I felt scolded by those endings, in which compelling emotional difficulties were “solved” with a quick plot turn or an upbeat change of heart. Why didn’t problems get solved so easily for me? Why did I brood, why did my emotions stick so? If my adult self had one guiding thought as I worked toward the final version of Matasha, it was that I was never going to condescend to my main character. She might see out of 11-year-old eyes and have some amusing misperceptions about things, but her feelings were not less complicated, or stubborn, than those of the adults around her. Her speculations might be limited by her age, but they were intelligent speculations.

Why didn’t problems get solved so easily for me? Why did I brood, why did my emotions stick so?In getting to know and love this character, this Matasha, I discovered more affection for the girl I myself had been—the ruminator, the adult wannabe, the kid who had “ideas”—and appreciate aspects of her I had undervalued before. Spiritedness. Curiosity. Honesty. The willingness to make mistakes. Perhaps, in writing Matasha, I was fashioning myself, through a species of time travel, into a friend for my old self, or even a mentor, someone who could guide her gently through the tricky work of starting to grow up.

There are all kinds of children and therefore rightly all kinds of children’s novels. Some kids want fantasy and intense danger. Some want wacky hijinks or lots of descriptions of bugs. For others, kids like I was, interiority itself promises excitement and poses dangers; thinking and feeling—and thinking about feelings—are also great adventures in life.

These are the kids for whom I wrote my novel.

__________________________________

Matasha by Pamela Erens is available now from IG Kids Publishing.