Mirinae Lee on Learning How to Write About War

To have your work compared to a monumental literary title is always an honor and a burden to a writer. My debut novel, 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster is often described as a historical novel similar to Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko. Like Pachinko, my novel is a story of a Korean family surviving the turbulence of the 20th century, the most dramatic period of modern Korean history. But some of the early readers of my novel, especially those who read it mainly with Pachinko in mind, voiced a complaint that 8 Lives is at times too dark and too devastating to read.

If it were up to me to name one book that was the most influential for 8 Lives, I would choose The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Alexievich rather than Pachinko. I came across this groundbreaking work of literature about six years ago when I was just beginning to develop ideas for my debut novel, and it upended my literary world in the best way possible.

Only a half hour after I first opened the book in the University of Hong Kong library, I found myself crying uncontrollably despite the spectators in the room. I’ve never shed so many tears reading a book. The Unwomanly Face of War, an innovative work of literary nonfiction by the Nobel-prize-winning Belarusian journalist, features hundreds of different voices of women from the former Soviet Union, who narrate their pained personal accounts of fighting in the Second World War. This oral history portrays a vast range of human emotions in their full intensities and subtleties, through the raw languages of numerous women who are the firsthand witnesses and survivors of the war’s brutality.

I was surprised by how similar many of their stories were to those of my family I had grown up listening to, the testimonies of war and its ongoing aftermath. The story of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers reminded me of my grandmother’s account of witnessing and narrowly escaping rapes by American soldiers during the Korean War; the landmine accident that took the life of a Russian soldier in his hometown, after surviving years of war, resembled the one that took my grandfather’s leg two decades after the war was over; stories of townspeople killing each other, divided by the conflicting politics of the Germans and the Communist partisans, were identical to those of my grandparents, split by the violent confrontation between Communist guerrillas and the Allied Forces; the hunger the Soviets suffered, during and after the war, was akin to that of my great-aunt who survived a famine in North Korea that wiped out one-third of her region’s population; recurring traumas the soldiers faced even long after they won the war made me think of my sleepless, alcoholic uncle, still reeling from the memories of his inhuman military training as a spy to be sent to North Korea.

It was as though they were telling me and my family that we weren’t alone in these memories of hushed atrocities.Just like my family, the various narrators of The Unwomanly Face of War bore the brunt of war and suffered its aftershocks in the guts. What I admire the most about Alexievich’s writing is that it does not flinch from the atrocities of war, that it lets the survivors speak their own languages, still raw and pulsing with visceral pains. Alexievich writes in the beginning of the book that the manuscript of The Unwomanly Face of War has been rejected by publishers for years under the same verdict: the violence of war described in her work is too horrendous, too realistic. But Alexievich refused to censor or tone down the words of her subjects to make them more palatable.

What I hoped to do with 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster was similar. I tried to depict the pains of my family and those who endured the same brutalities with an unflinching eye. It was indeed agonizing for me to recall the story of my nineteen-year-old grandmother escaping a rape by American soldiers during the Korean War, with my two-year-old father holding her hand and his little sister inside her belly.

For me to write about it in details, while pregnant with my second child, just like my grandmother in her story, was even more painful. It isn’t always easy to gaze at an open wound, but however painful it is to hear such stories or to write about them, it is much more difficult for the wounded to share them. Alexievich writes that countless women she interviewed often cried a lot, shouted. Some swallowed heart pills, called an ambulance after she was gone. Even so, they begged her to come back: “Be sure to come. We’ve been silent so long. Forty years…,” they told her.

Reading hundreds of wounded voices in their raw truths was, to me, devastating. And yet it was also incredibly comforting and uplifting. It was as though they were telling me and my family that we weren’t alone in these memories of hushed atrocities, that our little stories of suffering, although we are no heroes with shiny medals and badges, deserve to be heard—just like theirs.

In the prologue of 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster, an obituarist says “sometimes the best thing you can give to others suffering is your ears.” I hope I have fully given mine to my characters, without turning my eyes away from their open wounds no matter how frightening they might be.

___________________________

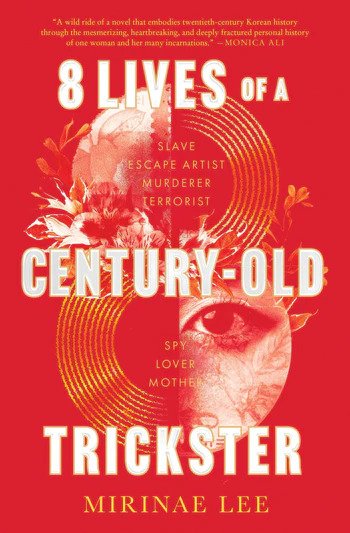

8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster by Mirinae Lee is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.