Myriam J.A. Chancy on Writing Haiti and Honoring Its Local Realities

This tumultuous past year and a half has been a mixed time for Myriam J.A. Chancy, whose new novel, What Storm, What Thunder, is published today: “I’ve been lucky in the sense that I have been with my spouse, whom I married during the pandemic, in an online wedding that our family and friends could attend (virtually, from seven countries!), and so it’s been a somewhat joyous time for us though she is far away from her native Brazil and won’t be able to return there in the short term. I also have not been able to visit my father, who is 87 and lives in Canada. We both lost family in the last year and, personally, I lost friends and family members with whom I was looking forward to sharing the novel.”

It’s also been a productive time, she explains. “My father put out an album of Haitian folk songs, in collaboration with Montreal-based, Haitian composer David Bontemps, which features photographs I took in Jacmel, Haiti, when we were there together in 2013 and my last academic book, Autochtonomies, which was supported by a Guggenheim fellowship, came out weeks before the pandemic, in late February 2020.”

Her work as an academic—she holds a chair in the humanities at Scripps College—hasn’t changed much, except that she had to learn many new technologies for teaching online effectively (“I’m in love with Canvas and FlipGrid!”). “I also spent most of the last year getting What Storm, What Thunder ready for press, working with Tin House for the acquisition edits of the book through to first printing. I haven’t been writing much new work, except for some recent, commissioned essays on the August 14, 2021 earthquake, one of which has already appeared with NPR Books.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How has that August 14, 2021 earthquake in Haiti affected you? I noticed that you updated the Haiti Relief Funds on your website within days.

Myriam J.A. Chancy: The August 14, 2021 earthquake in the Southern Peninsula of Haiti was certainly disruptive, especially following less than a month on the heels of the assassination of the Haitian President, an assassination which still has not been resolved in terms of who ordered and executed it. When I heard the news in the early morning of August 14th, I thought at first that it was a hoax, or perhaps a news report about the 2010 earthquake. Once I realized that it was real and checked the news, the memories from 2010 flooded back, the fear that what had happened already was happening again, readying oneself for the loss of life, of heritage—all of that swept over me.

Once I knew that the earthquake had not affected the capital, I was somewhat relieved since what remaining family I have are there but then I soon started to check on the people I knew in the affected areas and found that one friend had lost family, part of her house, and needed help to evacuate another family member for emergency medical care in the US. She had more resources than most so this started a conversation between us about making sure to pass on information I was finding for her to others who might need it, such as access to public air evacuation services. From there, I went on to contact people and organizations that I trust and have worked with and supported for a long time, even prior to 2010, to find out what organizations they recommended for those who want to donate to Haiti relief and rebuilding efforts.

It’s not Haiti that needs to be troubled, but those looking on.This all happened within 48 hours. I was shocked, actually, to see that on social media, many people were saying that donations should not be made to Haiti because of how aid after 2010 was mishandled but the caution should have been not to make the error of donating to large NGOs (like the American Red Cross) whose mandate is not to provide medical aid and rebuilding assistance over the long term solely in one country, and not to donate to NGOs that demonstrated lack of transparency in the last eleven years. We should be assisting Haiti and Haitians through donations and, in this case, donations to organizations working specifically in the Southern Peninsula because donating to “Haiti” usually means donating to organizations in Port-au-Prince, which, except in rare exceptions, may not have ties to rural areas beyond the capital.

Although I know that there are donation drives, one has to be very careful about that, as this can lead to accumulations of unwanted goods within the country. Unless you are working with a specific, Haiti-based organization requesting specific items that are for short-term use, the goal should be and should have been to ensure that when people donate that they research the organizations that they donate to, make sure that those organizations are working with those affected on the ground, better even, if they are led by Haitians themselves, and that they have a long track record of leaving a community better off than they were as a result of their presence. If those things aren’t discernible, then one shouldn’t donate.

I was also surprised that many people didn’t know where to turn in seeking out places to donate, which means that, for many, Haiti was out of mind, which is also one of the reasons that I decided to write the novel, many years ago. If we are moved by a place, it is also up to us to remain in contact with the region, to follow up, to make organizations accountable as well as keep ourselves accountable. It’s difficult to witness the extent to which Haiti and Haitians are forgotten when the country has contributed so much to the world beyond it, historically, culturally, sonically.

JC: At what point after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti did you decide to write What Storm, What Thunder? And how will the August 2021 earthquake find its way into your discussions as you launch the novel?

MC: This was not a novel I was planning to write. In fact, it was an idea that I shelved from the very beginning because I had a novel come out in February 2010, which was responding to the devastating hurricane cycle of 2004 (The Loneliness of Angels, published in the UK), and when I gave readings at the time, I was sometimes asked if I shouldn’t be “taking advantage” of the moment and writing about the earthquake. My answer was always an adamant, “no.” Furthermore, as a specialist in Haitian women’s literature (I wrote the first book in English on Haitian women’s literature in 1997, Framing Silence: Revolutionary Novels by Haitian Women which looked at Haitian women’s literary production from 1929 to 1994), I was called upon to give many talks right after the earthquake on the situation on the ground, best practices and consequences of the earthquake on vulnerable communities. That meant that I was reading everything that was coming out in the press, from Europe to the Americas, about rescue and rebuilding efforts, and also forming opinions from people I spoke to as many of us coordinated efforts to connect Haitians on the ground with resources outside of Haiti, and so on. I was literally giving talks almost every week for almost six months (while also teaching full time) and this work eventually stretched into three years, including reviewing books coming out with university presses by various authors, many of them not academics or Haitianists, who had written on the post-earthquake situation from various disciplines (legal, architectural, etc.). Writing a novel on the earthquake was the furthest thing from my mind, even though I was dealing with the consequences of the earthquake as a scholar, activist, and organizer for years after it.

What did change my mind was seeing the work of other artists in the Caribbean, particularly the work of painter Leroy Clarke, in Trinidad, who was painting a series on Haiti that he had started in 1986, left unfinished, and returned to after the earthquake. At the time, he had never been to Haiti, never met a Haitian painter or studied Haitian styles of painting, and yet, the paintings (of which there were over seventy when I visited him) bore singular traits of Haitian aesthetics and sensibilities. He asked me what they conveyed, and it was in this process that the novel was born. (Regretfully, Clarke passed away just a few weeks ago; he is one of the people I was waiting to share the novel with, and I won’t have a chance to do that.)

After my encounter with Clarke in his studio, I thought back to the conversations and stories I had received all those months and years of giving talks and realized that even though at the time I didn’t really understand why so many came forth with their stories, after visiting Clarke, I realized that they had done so because I am a writer. They told me their stories as they would tell a doctor their ailments and, like a doctor, I had to figure out the source and solution to those ailments. In my case, the solution was to honor the trust and grief that shadowed the stories, to write something true about the experience of the earthquake.

The spine of the novel came to me, then the characters, their names, their ages, who they were then, whether they were alive or dead.So, the novel is not based on the stories but informed by them. I also thought back to my own experiences visiting sites on the ground, reflected on what I experienced, heard, exchanged, those first years, and what I had read from news reports and blog posts like Beverly Bell’s (from Bell, for example, I learned early on that locals in Port-au-Prince called the earthquake “douze,” which I found to be true in my returns to Haiti, and I used this as a refrain through the novel to honor local reality). Within days of returning from this trip to Trinidad in 2013, I had outlined the novel and got started on the writing.

JC: What inspired your title?

MC: The title comes from a few different sources in the novel. There is the Frederick Douglass epigraph from his 1852 essay, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Then, the character of Dieudonné, we are told, from another character’s perspective, Sonia, sensed the coming of calamity and she describes his sensing “a too-clean smell that comes in the minutes before a hurricane or a thunderstorm, when the skies are clear and crackling with electric energy, before the winds pick up and snap fronds clean from swaying palms whose rhizomes grasp the earth like tentacular fists.” The collapsing of the hotel in which they both work, and in which a third character, Léopold, finds himself trapped, is also described as “thunderous.”

And, finally, there is the quote from Revelation 16: 18-19, which is found in Didier’s section (Didier is a musician turned cabbie in Boston): “And there were voices, and thunders, and lightnings; and there was a great earthquake, such as/ was not since men were upon the earth, so mighty an earthquake, and so great.” The title suggested itself from these repetitions of “thunder” and storms, associated with earthquakes. The quote from Revelation, of course, suggests the coming of an end time, a catastrophe of immense proportions while the Douglass epigraph is suggesting something perhaps more oblique.

In his essay, Douglass is suggesting that the (US) nation will only change to adopt people of African descent as equal citizens (we have to remember that this was written prior to the emancipation proclamation) when something calamitous brings the nation to ruin and that calamity is needed to rupture, not only those enslaved, but the nation itself, from their chains (of racial inequity, racial violence and strife, etc.). Once this occurs, he suggests, the nation might right itself, begin anew. This is very similar to a conclusion that James Baldwin drew in his pivotal essay of 1963, his response to the one-hundred-year anniversary of the emancipation proclamation.

hat essay ends with an allusion to a Negro spiritual: “If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!” Of course, not everyone will come to the epigraph with this association, but my intent, even though Haiti had a revolution by which the enslaved freed themselves, rather than were emancipated by former colonial powers, the situation of Haitians today is similar to that of the formerly enslaved in the US, in terms of how Haiti is positioned both hemispherically and globally as a “failed state”—especially by its Northern neighbors. I wanted to suggest through the Douglass epigraph that the 2010 earthquake, by revealing the infrastructural weaknesses of the State (to say nothing of the weakness of physical structures), revealed to all the very deep ways in which Haiti (to borrow from Walter Rodney) has been strategically “underdeveloped” by both colonial and neocolonial powers as a response to its forced independence of 1804.

I am suggesting not that the earthquake was needed but that its very devastation forcibly reveals to others the extent of the world’s neglect of the first Black Republic of this hemisphere. It’s not Haiti that needs to be troubled, but those looking on.

JC: Where did the ten voices in this polyphonic novel come from?

MC: There were originally thirteen distinct voices (twelve to honor the date of the earthquake and a thirteenth for spiritual reasons) but they were culled back to ten in the revision process to tighten the narrative pace, though those extra three characters (Dieudonné, Loko, and Paul) are still threaded through the novel.

In Haitian Vodou, the belief is that death is not an end of itself, that the dead, or at least the spirits of the dead, continue to live with us.It’s hard to say how they came to me. Literally, as I relayed before, after that visit to the painter’s studio in Trinidad, I sat down a few days later and tried to make sense of the encounter with him, with the paintings, and all that I could “read” there and the spine of the novel came to me, then the characters, their names, their ages, who they were then, whether they were alive or dead, what they wanted to say about their lives and experiences of the earthquake. It felt like a spiritual visitation, much like it seemed that Leroy Clarke had been visited by spirits in his studio, and painted alongside them deep into the nights for nights on end. Then, as one should, I followed the characters leads, let them be who they are as I wrote them into being.

JC: What made you choose these stories over others you’ve heard? You emphasize the role of women, and the vulnerability of women, in a disaster zone.

MC: Well, to be clear, I didn’t create the novel from stories that I heard. Since I had no intention of working on a novel about the earthquake when people came to share their stories with me after those talks I gave over a three-year-period, talks that I researched and supplemented from my own first-hand experience, I certainly wasn’t writing down notes about what I was told. The only story that I heard personally that informed some story lines came from a survivor of a hotel collapse, who was a man of color; and all he told me was that he survived that collapse and that surviving had changed his life path. He gave me no other information about how he was rescued, etc.

Since most of the survivor stories coming from the collapse of the hotel he survived, where UN and NGO workers were known to stay, were not people of color, that story got me thinking about all the local workers in that hotel, and others who would frequent the hotel and who had reasons for being there other than jobs related to Haiti’s crumbling infrastructure, or as aid workers. Having been in some of those hotels (though not stayed in them), I know that they are transactional spaces and so I conjured individuals like Sonia and Dieudonné, who “work” the hotel, and Léopold, who is a foreign national, but not a European one, and how they might have come to be there, and survived the collapse. Léopold was also my way to thread into the narrative some allusions to Trinidad, where the novel was sparked, and where I learned that there was a long tradition, among literary activists, of linking Trinidad & Tobago to Haiti’s history, particularly of the Haitian Revolution.

Other than that, the characters came to me from the vast amount of information I was gestating by the time I started writing. My job was then to streamline the information and to be clear about what the characters wanted to convey of their stories and how they were related to one another and what greater story this could tell of the earthquake. Because I have worked so much on issues pertaining to Haitian women (and all of the women leaders of the main women’s organizations at that time died in the earthquake), and this is an area I know best, I did make a deliberate choice to highlight the varied conditions and positions of Haitian women and girls through the earthquake. I’m glad that this comes through clearly in the novel.

JC: I’m curious about how you created the order in which you tell the stories. You begin and end the novel with Ma Lou, the market woman, as your narrator; she tells us in the opening pages, “I watched. That’s what old market women do: we watch.” What made you decide to use her narrative as the framework?

MC: So, the novel went through several iterations in terms of the order of the characters and some of that changed over time, through the editorial process. I ended up with an order that was closer to my first draft, but the decision to make Ma Lou central to framing the narrative came more at the end of the process, when I realized that she deserved to be the character who holds the space for the others, as so many market women do. The inspiration for her comes not only from market women in general but from my great-grandmother, my mother’s grandmother, who was a market woman who eventually had several other women working for her with a stall in the marché de fer (covered steel market) in Port-au-Prince and was so successful that she was one of the first people with a car in the city, and also was able to purchase a two-level home where my mother and her siblings were raised, without any male support (I think she was widowed early and did not inherit anything).

I truly believe that if market women were given the possibility of directing the affairs of state, the society would be better off. But, beyond this, these women are the eyes of the city, of the society: everything comes through the market, so it made sense to make Ma Lou central to the narrative, its driving force, and to make that point about their value to the local economy as well as being the societal glue.

JC: In the first chapter, Ma Lou witnesses what happens to three children she knows. Jonas, eleven, who has bought an egg from her and then, instead of going straight home, as his mother asked, stops off at a neighbor’s to watch a soap opera on TV. Inside, he is seriously injured when the earthquake hits. His two sisters, aged five and two, die when the building collapses over where they are playing in the streets. Sara, their grief-stricken mother, narrates the second chapter from a refugee camp. Their father, Olivier, brings her Jonas, whose injured legs have been amputated, then disappears. In a mysterious way you create a weaving in which the ghosts of these three children hover over the rest of the book (Jonas even serves as a narrator of one of the final chapters). How did you do that?

MC: For me, so much of this novel is about the dead, rather than the living, so it was important for me to weave into the structure of the novel a feeling of the presence of the dead, an animating life force. In Haitian Vodou, the belief is that death is not an end of itself, that the dead, or at least the spirits of the dead, continue to live with us, so I wanted to bring that feeling to life within the novel. The three children, especially Jonas, haunt the novel, like they haunt their mother, and, hopefully, the reader, beyond the book.

JC: Your narrators also include Ma Lou’s granddaughter Anne, who is among the last to tell her story. She is on a mission to build affordable structures in Kigali, Rwanda, when the earthquake destroys Port au Prince. Her tale describes what can be learned from the outside, via press reports, calls, emails, social media, and also Anne’s deep sense of grief, first at the death of her mother in late 2009, and then the earthquake: “I thought of…all the bodies buried beneath the rubble of unstable buildings.” Anne also recognizes the names of the Haitian women activists in her field who died in the quake. What role does her perspective play within your story?

MC: Well, like any author will tell you, we leave parts of ourselves in the characters we create. There is a little bit of me, or my experience, in each of the sections, in each of the characters, but Anne, to some degree, reflects my own experience of having witnessed the earthquake from afar, and having to be a conduit for others seeking assistance with finding survivors or getting aid into the country or to people on the ground. Beyond this, I have engineers on my mother’s side, whose buildings did not fall in the earthquake, and because of my own early interests in architecture (I started as an undergraduate in the architectural studies track of an environmental studies program before switching to the humanities), and the shock of seeing so many of the landmark buildings fall that night, I wanted to reflect on what a Haitian perspective might be in wanting to take part in rebuilding efforts, but also the limits of that very personal desire.

I also had spent some time in Rwanda, because of another book I was writing at the same time, my last academic book, and was struck by the similarities between what had happened in Rwanda and the strife between Haitians and Dominicans on the island, to say nothing of the experience of violence and gendered violence during the Duvalier dictatorship. Anne gave me a space from which to explore these issues and also to connect her to two very different narratives or commentaries on social class in Haiti, first through her father, Richard, the Haitian-French water bottle magnate, and her grandmother, Ma Lou, who remains a humble market woman. She reflects my own experience of being from a family with individuals in widely divergent social classes or even widely different ethnic make-ups.

JC: You were born in Port-au-Prince, descended, you write in Framing Silence, from “Toussaint L’Ouverture’s oft-forgotten sister, Genevieve Affiba, who is absent from historical reproductions of the Haitian Revolution (1786-1804). Does that heritage have an influence on this novel?

MC: Well, I haven’t thought about that. If anything, I would say that knowing that I’m descended from Geneviève Affiba, and that very little is stated in the record books about her story, though some of her children, who fought in the Revolution alongside her brother, are, makes me reflect on who is forgotten from history, and, of course, who gets to tell the narrative. This relates to why Ma Lou has such a central place in the narrative.

JC: Speaking of novels by Haitian women, what contemporary work inspires and impresses you? (I have never forgotten Roxane Gay’s An Untamed State, and of course Edwidge Danticat’s work is extraordinary.)

MC: Roxane and Edwidge’s work is great; I have loved reading Roxane’s longform essays during the pandemic and I just published an essay on Edwidge’s Brother, I’m Dying, which is for me one of her most vital works, in a collection out of Cambridge on her varied works. But, I have to say that the novel took me a very long time to write and I mostly didn’t read Haitian writers during that time because I didn’t want to be influenced by what others were writing, although I did read Yanick Lahens’s, Failles, because I got it in Port-au-Prince in 2011, and couldn’t stop myself. It’s both the story of a couple falling in love and a reflection on the condition of Port-au-Prince after the earthquake by the author. Lahens has published many books since and won France’s Prix Femina for Bain de Lune, published in 2015, and recently translated into English as Moonbath.

My other recent discovery among Haitian women writers, is Emmelie Prophète; I would read anything she publishes! The first book I read by her was Impasse Dignité, which tells the story of a group of people living on a street named Dignity. Impasse also means “dead end” so there’s a pun in the title suggesting that dignity isn’t possible for these humble people. The writing is beautiful, poetic. This novel also refers to the 2010 earthquake but in a completely unexpected way which I won’t spoil for others by describing. This work is not translated but, luckily for English readers, Prophète has a forthcoming translation called Blue, which reads (in the French) like a love letter to Port-au-Prince from the perspective of a character who is leaving Haiti. I think Lahens and Prophète are two Haitian women writers that we should expect to read more from and who hopefully will be read alongside those working in English.

JC:What are you working on now?

MC: Well, I don’t like to talk much about work in progress as it can kill the process for me. But I am reflecting on the losses of the last year, of the past few years, actually, and the legacies that disappear as generations are lost. For instance, my mother and her sibling group passed away within a few years of each other very recently and, as a result, I’m working on a novel that will bear on sibling relationships in Haiti, and the relationship to the Dominican Republic (my maternal grandfather was Haitian of Dominican descent which is considered unusual these days). Where this will go, I’m not sure, but I’m looking forward to finding out!

_______________________________________________

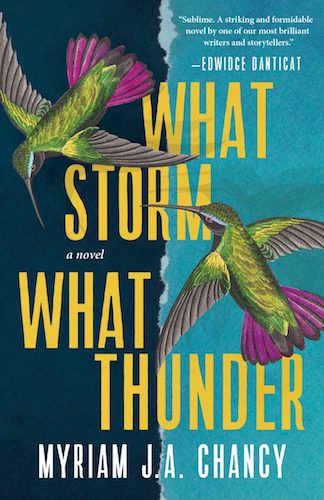

What Storm, What Thunder is available now with Tin House Books.