Nature Writing is Survival Writing: On Rethinking a Genre

If there were a contest for Most Hated Genre, nature writing would surely take top honors. Other candidates—romance, say—have their detractors, but are stoutly defended by both practitioners and fans. When it comes to nature writing, though, no one seems to hate container and contents more than nature writers themselves.

“‘Nature writing’ has become a cant phrase, branded and bandied out of any useful existence, and I would be glad to see its deletion from the current discourse,” the essayist Robert Macfarlane wrote in 2015. When David Gessner, in his book Sick of Nature, imagined a party attended by his fellow nature writers, he described a thoroughgoing dud: “As usual with this crowd, there’s a whole lot of listening and observing going on, not a lot of merriment.”

Critics, for their part, have dismissed the genre as a “solidly bourgeois form of escapism,” with nature writers indulging in a “literature of consolation” and “fiddling while the agrochemicals burn.” Nature writers and their work are variously portrayed, fairly and not, as misanthropic, condescending, and plain embarrassing. Joyce Carol Oates, in her essay “Against Nature,” enumerated nature writing’s “painfully limited set of responses” to its subject in scathing all caps: “REVERENCE, AWE, PIETY, MYSTICAL ONENESS.”

Oates, apparently, was not consoled.

The persistence of nature writing as a genre has more to do with publishers than with writers. Labels can usefully lash books together, giving each a better chance of staying afloat in a flooded marketplace, but they can also reinforce established stereotypes, limiting those who work within a genre and excluding those who fall outside its definition. As Oates suggested, there are countless ways to think and write about what we call “nature,” many of them urgent. But nature writing, as defined by publishers and historical precedent, ignores all but a few.

The nature-writing genre emerged in the late 1700s, during the peculiar moment when nature, as Europeans and North American intellectuals saw it, was no longer fearfully mysterious but not yet endangered. The scientific classification of species had brought some apparent order to undomesticated landscapes, allowing writers such as William Bartram, a botanist who traveled through the American South shortly before the Revolutionary War, to perceive not a tangle of flora and fauna but “an infinite variety of animated scenes, inexpressibly beautiful and pleasing.”

Such “appreciative aesthetic responses to a scientific view of nature,” as the writer and naturalist David Rains Wallace once described them, were products not only of their time and place but their culture and class. Scientific views of nature are not the only possible views, of course, and as many anthropologists and linguists have pointed out, the concept of “nature” as a collection of objects, separate from but subservient to humans, is also far from universal.

In the 19th century, many of the thinkers we now call nature writers took some exception to the genre’s original project. While Ralph Waldo Emerson famously saw human transcendence as the primary purpose of the non-human world, his rebellious protégé Henry David Thoreau was more interested in other forms of life for their own sake, and more willing to get his literal and metaphorical boots muddy. John Muir, though notoriously dismissive of the human history of the Sierra Nevada, had unusually egalitarian ideas about other species, considering even lizards, squirrels, and gnats to be fellow occupants of the planet.

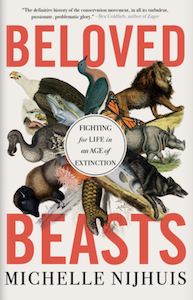

As I learned while researching my book Beloved Beasts, a history of the modern conservation movement, the rise of the science of ecology in the early 20th century made it ever clearer that the boundaries between humans and “nature” were more linguistic and cultural than physical. Rachel Carson, who cited Thoreau as one of her primary influences, further expanded the nature-writing genre by tying the fate of other species to the fate of human bodies.

There are countless ways to think and write about what we call “nature,” many of them urgent. But nature writing, as defined by publishers and historical precedent, ignores all but a few.Any genre can only stretch so far, though, and the limitations of nature writing are inscribed in its very name. Nature writing still tends to treat its subject as “an infinite variety of animated scenes,” and while the genre’s membership and approaches have diversified somewhat in recent years, its prizewinners resemble its founders: mostly white, mostly male, and mostly from wealthy countries. The poet and essayist Kathleen Jamie calls them Lone Enraptured Males.

Meanwhile, writers in every genre and discipline are wrestling with the relationship between humans and the rest of life, recognizing that while writing about other species is often about wonder and uplift, it is also, inevitably, about survival—the survival of all species, including our own. Amitav Ghosh, whose novels often follow the connections among species and habitats—humans and snakes, tigers and dolphins, land and sea—recently published The Nutmeg’s Curse, his second book-length essay about the literature, history, and politics of climate change. (The first was The Great Derangement, published in 2016.)

Science-fiction writer Jeff VanderMeer returns again and again to the unstable boundaries between humans and other species, most recently in his novel Hummingbird Salamander. Margaret Atwood, a dedicated birdwatcher, wrote that the sight of red-necked crakes “scuttling about in the underbrush” in northern Australia inspired her dystopian MaddAddam trilogy. Historians such as Dina Gilio-Whitaker, the author of As Long as Grass Grows, and Nick Estes, the author of Our History Is The Future, document the damage done to Indigenous cultures and all species by centuries of capitalism and colonialism. These and many other works acknowledge that humans are both observers of and participants in the network of life on earth—and that our roles, while often destructive, can be constructive, too.

Today, the nature-writing genre reminds me of the climate-change beat in journalism: the stakes and scope of the job have magnified to the point that the label is arguably worse than useless, misrepresenting the work as narrower than it is and restricting its potential audience. The state of “nature,” like the state of the global climate, can no longer be appreciated from a distance, and its literature can no longer be confined to a single shelf. If we must give it a label, I say we call it survival writing. Or, better yet, writing.

__________________________________

Michelle Nijhuis’s book Beloved Beasts is available through W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2022.