Not an additional ornament: as he prepares to direct Handel’s 'Tamerlano', Dionysios Kyropoulos discusses bringing historical stagecraft to the modern stage

|

| Costume design for Asteria in Handel's Tamerlano by Rachel Szmukler |

When Cambridge Handel Opera Company's production of Handel's Tamerlano, originally planned for 2020, finally opens in April 2022, the director will be Dionysios Kyropoulos, with James Laing as Tamerlano, Christopher Turner as Bajazet, Thalie Knights as Andronico, Leila Zanette as Irene and Caroline Taylor as Asteria, and Sounds Baroque, conducted by Julian Perkins, artistic director of Cambridge Handel Opera Company [see my interview with Julian]. Dionysios is Professor of Historical Stagecraft at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama and the idea behind the production is to integrate the stagecraft of Handel’s time with the music of his opera, supported by leading period instrumentalists.

|

| Dionysios Kyropoulos |

Dionysios trained as a singer and I first came across him singing in Danyal Dhondy's Secretary turned CEO, a radical re-working of Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona [see my review] whilst he was also doing an MPhil in historical stagecraft at Cambridge, and we subsequently met up for a chat about his intriguing ideas on the subject [see my interview from 2013]. That was eight years ago, so I was delighted to have another chat with Dionysios to talk about the challenges of staging Handel's Tamerlano and the combination of historical stagecraft with modern singers and stages.

Before Tamerlano opens on 5 April 2022, there is a chance to hear Dionysios in conversation with Julian Perkins, artistic director of Cambridge Handel Opera Company on 16 February 2022 as part of their Handel's Green Room online series.

Whilst we have had period performance practice for over 30 years or more, historical stagecraft seems to have somewhat lagged behind so that whilst many people will have encountered one of Handel's operas in a historically informed performance, far fewer will have encountered one staged with a view to historic stagecraft. Dionysios points out that musical performance styles have had a considerable journey since the first period performances, with several generations of teachers each learning from the previous ones. Performers have needed to come to understand the old repertory and embrace the musicality of the period performance style, so that modern performances have an improvisatory feel that is a world away from the sewing machine-like tempi of the first performances. Such developments are necessary because we need to fill in the gaps in the oral tradition.

The performance needs to feel natural, an expression of what is in the heart

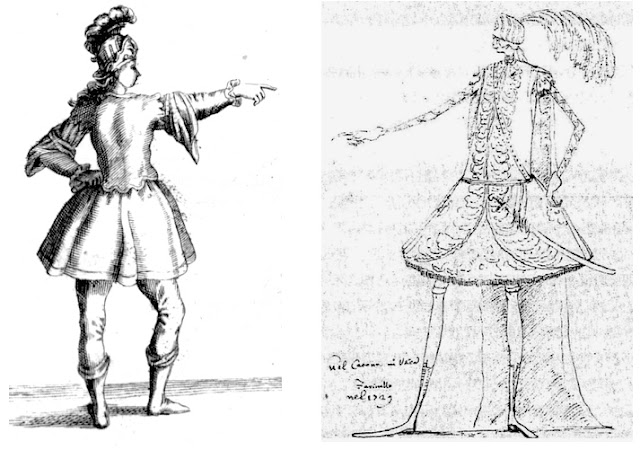

Similarly, historical acting is missing that element of improvisation. We know how historical performances looked, thanks to treatises and paintings, but the question is how to put the performance together to make it alive. A common ground in the contemporary writings about performance is the reference to nature, the performance needs to feel natural, an expression of what is in the heart. Whilst things should appear natural, this is nature beautified, there are rules and rhetoric is important.

The ideal is for a singer or an actor to understand the idea of character, but to act naturally, as themselves, yet shaped according to the rules. When people are trained in the basics then such things become second nature. The challenge is how to achieve this when there is a limited rehearsal period; if singers have to think about each gesture then the performance will be dead. Dionysios sees historical acting as being something that is often perceived as secondary, put on almost like a costume, but it needs to be second nature, seen as a different craft and not an additional ornament.

|

| A plate from Franciscus Lang’s Dissertatio de actione scenica next to a caricature of the castrato Farinelli |

If you use historical stagecraft in modern costumes in a modern theatre

it is not perceived as historical acting at all

What has always struck me when chatting to Dionysios about historical stagecraft is his practicality, perhaps arising from his background as a singer. For the last ten years, he has been creating a new method of historical acting, filling in the gaps in the historical record with modern techniques that work. He intends to train singers in the technique so that they can use these tools in a way that is not mechanical. As a practitioner of historical stagecraft, Dionysios sees a problem with terminology. For him, it is not a craft linked directly to period costumes. But if you use historical stagecraft in modern costumes in a modern theatre it is not perceived as historical acting at all! One of Dionysios interests is the combination of Baroque performance with modern stagings.

His teaching at the Guildhall School is based in the historical department. When working with undergraduates, the singers found the tips and techniques that he taught so useful that they could be used in modern performances. He gives them specific things that they can do, ways of showing emotion yet remaining calm inside. Dionysios points out that method acting does not work for singers, they need to be calm inside even though expressing violent emotions, and he refers to the paradox of the actor, that the best actor is one who shows emotion yet remains internally calm. Dionysios finds his techniques work well with singers, combating the danger of singers who convey extreme emotion musically yet their face shows as mildly inconvenienced. And these techniques are useful for any performance, including lieder, and Dionysios sees them more as acting for singers as historical acting, it is just that in Baroque performance there is a need to add extra details, to be more correct stylistically. We need to think of historical acting as a technique that singers can use, one of many in their repertory.

If a singer conforms to historical rules but is not natural then the performance looks fake

|

| The gesture of painful recollection from Siddons’ Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action |

Ideally, for such a production Dionysios would be working weekly with singers before rehearsals start. But for Tamerlano, Dionysios' approach will inevitably be something of a hybrid, yet one that works. Long before rehearsals started he had two full days of workshops with the singers, with lectures and practical sessions. And he followed that with monthly meetings with each singer to discuss how to apply the techniques, ensuring that each singer had their own relationship to historical acting. This means that when they start stage rehearsals, whilst Dionysios can suggest things, each singer will already have their relationship with historical acting. There are also online resources for the singers, including a repertoire of facial expressions that Dionysios describes as a gym for the face, and the idea is to ultimately train the unconscious so that they can be applied without effort on stage.

Of course, some find the historical acting techniques more difficult, whilst for others, they are a revelation. And as a teacher, Dionysios emphasises the importance of appearing natural. That is his first priority; if a singer conforms to historical rules but is not natural then the performance looks fake. A rhetorical gesture that looks fake is not a successful rhetorical gesture at all, as the fundamental idea of the gesture is to persuade and this fails if it is fake. Dionysios mentions the neo-Platonist question, 'Is a golden shield beautiful?', and the answer is no because utility plays an important role in beauty too. If a gesture is not natural, it does not persuade so, Dionysios starts from somewhere that feels natural for the performer and then moves closer.

In the past, historically staged operas that I have seen have suffered from the sort of problems that Dionysios talks about, and at best come over as rather like a choreographed dance. But Dionysios points out that the best dancers bring an element of sprezzatura to their performances so that the gestures almost appear improvised and all the hard work is hidden. And it is the same with singers, good performers can take the gestures that he suggests and make them seem improvised.

Dionysios aim is to work from nature in a way that each performer will feel comfortable. Tamerlano is a psychological drama where character development is important. It is also a claustrophobic opera, everything happens indoors and it begins in a prison cell. So, Dionysios is working with the designer and the lighting designer to ensure that everything conveys the dramaturgy of the piece. Sets and costumes will be as simple as possible, modern but timeless yet incorporating archetypal elements that will tell you what each person is, without conveying a set period. So that changes in Bajazet's costume through the piece will reflect his change of status from ruler to a prisoner. But there are also different nationalities in the characters, and the audience must know who each of them is. The lighting designer, Trui Malten, is someone with whom Dionysios has worked before and she can play with shadow, chiaroscuro perfectly. The advantage of a simple set with a strong lighting plot is that they will easily be able to plot the changes of location and character without the interruption of major scene changes.

If you analyse the role without preconceptions then Tamerlano is a Sanguine person

|

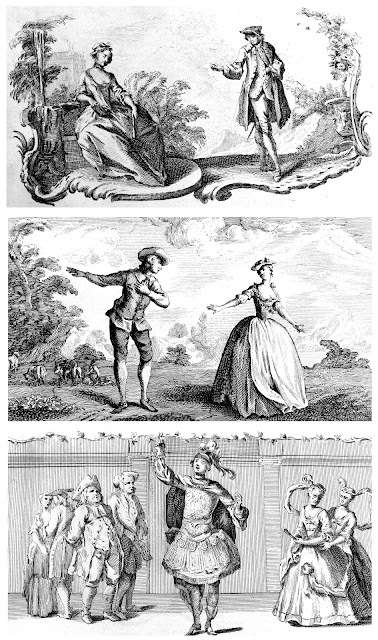

| Illustrations from Bickham’s songbook Musical Entertainer depicting staged scenes, all of which employ gestures and decorum deriving from the ideals of classical beauty |

Dionysios sees the whole opera interpreted in an historical way using the Four Temperaments (sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic). Whilst these were important in 18th-century medicine, they permeated life, including acting.

For the singers, he brings out that each Temperament is connected to an Element, sanguine to air, choleric to fire, and this changes the movements and gestures for each character. A choleric person's anger will not have the same fire as a sanguine person's anger. And consideration of the Temperaments enables singers to put the emotions in the context of their particular character.

Dionysios' whole interpretation is centred on this historical understanding of the Temperaments, and he does not wish to simply reconstruct a museum piece that will be seen as quaint and bizarre. Instead, he wants to move a modern audience and do justice to the music, enabling it to fulfill its purpose which is to move the audience, thus creating a dramatic opera that is much more than pretty music. And the use of the Four Temperaments works with Handel's music so that the production is a conversation with the music.

The rules are there to be broken

Another point that Dionysios makes is that the rules are there to be broken, for effect, if this fits the dramaturgy. This always surprises his students, as he shows that the rules give them more freedom as being able to break the rules gives them more colours with which to paint. When a student gets this point, it is often a revelation. And for Dionysios, this revelation led him to concentrate on directing, rather than singing, finding historical acting a powerful tool for modern performance. So, in Tamerlano the rules will be followed, yet broken for effect to convey the emotional journey of the character.

Always remembering that the performance is there both to move and to bring pleasure. For this reason, the opera will be cut. In Handel's time, people could come and go during performances, and would routinely attend multiple performances. For a modern audience, there are limits to the amount of time you can expect them to sit in a dark theatre; Dionysios is aware of the need to both entertain and move. He has spent many months on the cuts, ensuring that characters are not compromised, that nothing is stripped away.

If the audience is engaged,

then the director does not have to add crazy things happening on stage

And when staging Baroque opera, Dionysios points out that the moment you do the right thing, engage with the character and words, use movement and gesture for rhetorical effect, then the audience is engaged, you draw their attention and the director does not have to add crazy things happening on stage. A production can be quite static, but the singers' use such dynamic postures that the performance is compelling and does not have to look awkward. Though, of course, it is tricky to get singers to embrace this sort of technique as they feel very exposed. Part of the reason for the static nature of the performance was that historical sets had a strong sense of illusion about them, you had to remain static otherwise you could break the illusions, hence using dynamic gestures whilst standing still. We no longer have these restrictions, but Dionysios feels that we can experiment and not move around simply for the sake of it. This is something that he discussed with the singers, and he describes the process of directing as more coaching the performers than telling them what to do.

|

| Tableau from a production of Purcell’s The Indian Queen, designed and directed by Dionysios Kyropoulos (photo by Pablo F. Juárez) |

After all, opera is such an artificial art form. Dionysios sees historical acting as helping an audience feel that the performance is real, counteracting that fakeness of it. When the performers do it, it can feel artificial but the audience perceives the style as more natural.

The performance will be sung in English. This is not historical but will aid comprehension. Every move the singers make is for a rhetorical reason, the gestures add variety and give the audience a clearer view of the text, so it helps that this is in English. The tradition of performing Handel in English in Cambridge is one that goes right back to 1985. Dionysios sees it as an advantage in a way because with a Da Capo aria the text is repeated a lot. With subtitles, you get one single mention of the text, but in translation you can listen to the singer and get the cumulative effect of the repetition, thus enabling the audience to get lost in the drama and not break away to extract the meaning of the words.

Handel's Green Room features online discussions with director Dionysios Kyropoulos, counter-tenors Lawrence Zazzo and James Laing, theorbo player James Akers and musical director Julian Perkins on 16 February, 2 & 16 March 2022, full details from the website.

Cambridge Handel Opera Company's production of Handel's Tamerlano is at the Great Hall, The Leys, The Fen Causeway, Cambridge CB2 7AD - 5, 6, 8, 9 April 2022. There is a study afternoon on 9 April 2022 at the Recital Room, West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge, CB3 9DP.

Full details from the company's website.