On the Flourishing of Black Literary Arts, Old and New

“Many of the leading publishers do not have a single brown or Black marketing, editing or publicity person. They are committed to institutional change and tailoring their offering to undeserved communities… for now. But they have to deal with reality now, have virtual coffees with the Black pros who have taken the baton from the Toni Morrisons in publishing and have been doing the work.”

–Yona Deshommes, Riverchild Media LLC

The publishing world is the tastemaker of the tastemaker. Many times the blueprint to The Culture is drafted by the publishing industry. Along with journalism, publishing is where the story we tell ourselves is drafted into manuscript format.

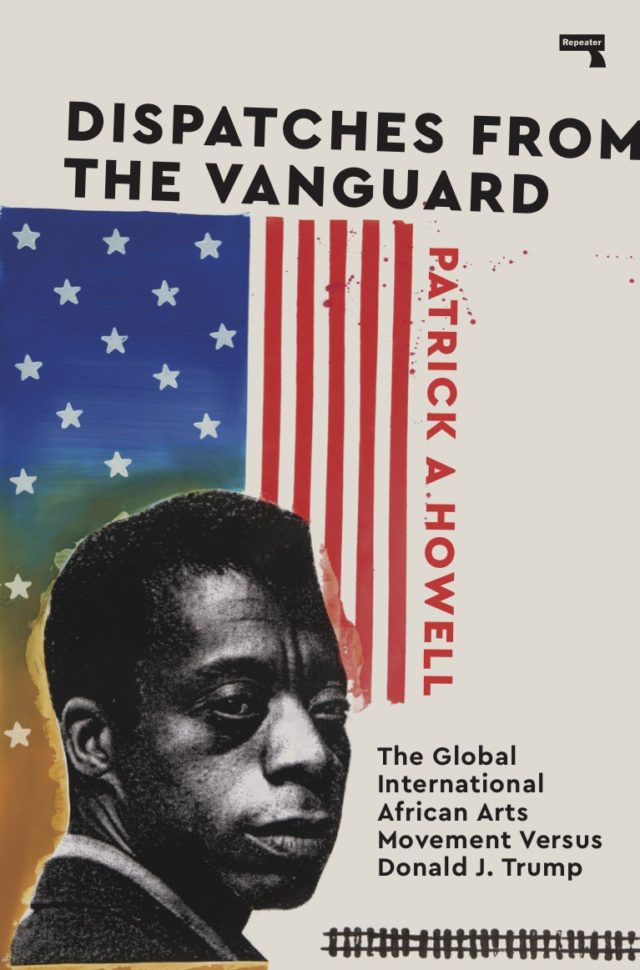

Patrick A. Howell, author of Dispatches from the Vanguard: the Global International African Arts Movement versus Donald J. Trump, has a conversation 30 years in the making with Max Rodriguez, a free enterpriser in the publishing industry who has published the Quarterly Black Book Review (QBR is now the Black Book Review) and the Harlem Book Fair (HBF) since the 1990s.

*

Patrick Howell: Max, I guess one of my opening salvos for you is what does it take to promote literature, the arts, and literacy for nearly 30 years? Why do this work?

Max Rodriguez: I believe strongly in moral courage… moral leadership. I believe that it is our collective moral fiber that has allowed us to survive and even thrive within adverse societal climates. Moral leadership, one might say, is our superpower. Yet that leadership, while a powerful contribution and a model for humanity, is left largely unacknowledged and uncelebrated. This is especially true in the literary arts where the best of our writers—Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Toni Morrison, Chinua Achebe, Ben Okri, Derek Walcott, and many others like them—are seen as the exception rather than exceptional.

PH: That’s a great point that Ishmael Reed spoke to in Dispatches. Tokenism, or what he called “Occupation of the Black Experience” or “one at a time-ism.” That was one of the driving forces behind moving on from my business in the investment banking industry and co-founding a production company in the storytelling business. America keeps projecting one percent of our stories over and over and over to the world like a propaganda machine with a political and social agenda—white nationalism in America.

What an incredibly fertile opportunity to do what you have done with your various platforms—insist on telling our stories. As a matter of fact, you and I have had sort of an ongoing 30 year dialogue about what I like to call “the power of definition” and the space where so much of your work focuses on is defining us for us by us. To your point, our exceptionalism is our modus operandi. We really have to be exceptional to survive, master and exceed the standards of the industries in which we make a living.

MR: Yes, that otherly imposed definition of exceptionalism excludes hundreds of years of African-descendent literary genius and accomplishment—hundreds of years of telling our stories, of etching our history in stone, of being acknowledged as contributors to the history of Man.

In American publishing circles, we have historically experienced 30-year cycles of peaks of interest in African American books, authors, and writing—each lasting plus or minus 12 years. Briefly, the early 1900s found African American cultural interest in the work of Paul Laurence Dunbar and Charles Chestnut. The late 1920s and early 1930s embraced the music, art, and literature of the Harlem Renaissance. The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s translated the invasive, disruptive and powerful rhetoric of “Black Power” into digestible, visual form. A resurgence of interest in Black literature again flourished with the 1990s publication of Terry McMillan’s blockbuster, Waiting to Exhale.

With too few exceptions, the absence of black Diaspora stories had been standard operating procedure in publishing houses.

Is it possible that within this obvious continuity of expression, we simply stopped writing? Might it be possible that we collectively “dropped the mic,” walking away from the urgency of telling our stories? I think that is most unlikely. In fact, in my work throughout the years, I have discovered countless books by African American authors that—as with most published titles—just did not find their way to the public arena.

PH: This feeds into the current national discussion of Black Lives Matter, systemic racism and institutional discrimination. Specifically, I call it the “Hollywood Industrial Complex” where the artistic descendants of the racist D.W. Griffith (Birth of a Nation, 1915), still have the audacity to green light what stories of ours will be told to the world. They have a political, cultural and social agenda and it is imbued with the toxic stank of white patriarchy. It’s like when former president Bill Clinton eulogizes Congressman John Lewis, negatively framing Stokley Carmichael (Kwame Ture). Your pass to the Black community is revoked! Permanently.

MR: With too few exceptions, the absence of black Diaspora stories had been standard operating procedure in publishing houses. But American culture fills the absence of our stories with stories of its own. And their story—tempered by exclusion and fear—transforms their absence of interest into a perceived absence of African American intellectual engagement, curiosity, self-assessment, and self-ownership.

This is so far removed from the truth. African American publishers have served readers for decades. John Johnson’s Ebony and Jet magazines long served as cultural lifelines. Haki Madhubuti’s Third World Press in Chicago recently heralded its 50th year in book publishing. Black Classic Press publisher Paul Coates (father of National Book Award-winning author Ta-Nehisi Coates) has published award-winning author Walter Mosley.

Wade and Cheryl Hudson, founders of JustUs Books, an African American children’s book publisher, are celebrating 30-plus years of service to readers. Kassahun Checole, publisher of Africa World Press and Red Sea Press, founded these two world-renowned publishing and distribution houses in 1983 and 1985, respectively, to focus on African and African American issues. These sister presses have since published over 1,400 titles. As a group, these publishers hold the space for African American publishing from which hundreds have been inspired into publishing enterprises.

PH: Absolutely, and there is also from those rich roots the Chicago Review Press and Broadside Lotus Press and Harriet Tubman at Loyola Marymount University, a press run by Elias Wondimu who is also the publisher of Tsehai Press. There is the rise of literary geniuses like Denene Millner, Kwame Alexander, Lisa Lucas, Jason Reynolds, and Nnedi Okorafor, with traditional presses as free enterprising souls who carry the treasure troves of our stories within their capable spirits. To your earlier point Max, we have an unbroken narrative from the beginning of civilization when our people imagined and invented language, story and universities.

MR: My work now is to eliminate those peaks—help ensure the filling of those valleys—creating an always-awareness and access to Black contribution; and like those publishers, writers, and “capable spirits,” to put in place relevant, commercially viable, publicly known and accessible structures that represent the fullness of the African Diasporic experience, in the U.S. and throughout the world. We are one voice with many stories. This year’s virtual Harlem Book Fair marked the launch of the #GLOBALIAam calling. Through access to digital media, our possibilities appear endless.

The perception of absence, however, remains persistent. I recently read an article online in the New York Times focusing on African Americans within the publishing industry. Five individuals were highlighted—a marketing director, an editorial director, two literary agents, and a bookseller. They each spoke eloquently about their vision for African American books. The elephant in the room was the absence of African American publishers.

With that oversight, the article projected three self-serving (and no longer sustainable) ideas: the continued marginalization of a vibrant intellectual African American viewpoint; second, that even within a digitally driven world, traditional publishing holds an exclusive access to the reader market; and that the African American experience, in writing, is best “authenticated” through traditional publishing. Self-imposed blinders will keep one from seeing the writing on the wall. The old marketing adage of “Location, location, location” has been replaced by “Content, content, content”—on whatever device and wherever a reader finds her/himself. And publishing like that is very non-traditional.

Ours is a continuation of those movements and voices that precede us—those ancestors’ shoulders upon which we stand.

The publishing industry’s “shiny object” had always been the lure of its highly-coveted distribution network. In a world of all things digital, however, even those distribution networks are being disrupted. The Author Channel, a streaming platform that I am producing on the Exposure on Demand TV Network through ROKU, Amazon Fire Stick, and Apple TV, gives readers daily access to books, authors, and publishers to over 160 million households, daily. Rather than serving as a competitor to still-viable distribution modes, digital streaming adds a highly-desirable access and delivery line directly to the ever-mobile reader.

PH: Your work in the space of American and world literature, arts and academia, includes not only the Harlem Book Fair but the (QBR; also, the Black Book Review) and, now, The Author Channel. Each decade you have provided a platform or hosted a virtual saints and souls revival processional in the canon of black arts. Your platforms have featured the creative genius and voices of Ishmael Reed, Maya Angelou, Cornel West, Sonia Sanchez, Michael Datcher, June Jordan, Amiri Baraka, Walter Mosley, Terry McMillan, Touré, Farai Chideya, Stanley Crouch, Nelson George, and Mark Anthony Neal.

I really feel that we seeded the Global I Aam or Global International African Arts Movement in 2014 at the Harlem Book Fair at the Schomburg Center for Black Culture. Is it possible to return to the formulaic ingredients that gave rise to the Harlem Renaissance—a space where our intellectuals and artists set the tone of global culture?

MR: We need not return; we need only to go forward. I remember that moment when we discussed the idea—the need—to name the flourishing of literary expression that we experienced in 2014. I had long resisted advocating the use of “the New Harlem Renaissance” as the name for the then-resurgence in arts and letters. In retrospect, one can see within that moment the seeding of GLOBAL I Am, the Global International African Arts Movement and its worldwide gathering of Diaspora voices.

PH: That’s right Max. We go forward. Even if American culture at large goes backward, we go higher still. Onward. Or, as Ishmael Reed said in Dispatches, “Black culture never stands still.” Ghanian international radio host of The Spin Esther Armah said it too in Dispatches, “Culture is never cast. Its beauty and its challenge is that is constantly evolving.” And there is a through line of cultural figures like Afrofuturist Ytasha Womack, American poet and culturalist E. Ethelbert Miller, Black Arts Movement co-founder Askia Toure or New York Times photographer Chester Higgins who also observe that Black culture will always reinvent itself.

And there is the new vanguard, if you will, of culture workers and outliers bringing the unseen and unheard to the center of our global culture—specifically people such as memoirist Lesley-Ann Brown, painter and philanthropist Danny Simmons, America’s global podcaster Tori Reid, Afrotopian Ingrid Lafleur, Resistance founder Sevan Bomar, novelist Morowa Yejide, Bay Area activists and painters Malik and Karen Seneferu, San Diego’s Khalif Price, jeweler Hanna Wagari, culturalist Darnell Moore or Princeton’s Dr. Imani Perry and Dr. Eddie Glaude, Jr.

MR: The work ahead of us is simple and straight-lined. The #GLOBAL I Aam movement was seeded in resilience and hope, hip hop, contemporary dance, spoken word performance, urban fiction, history, economic and scientific analysis, and the impact of technology on the African world. We need only gather those voices in celebration of our moral courage and leadership to make this movement our model of self-acknowledgement, validation, and contribution to the humanity of the world.

Ours is a continuation of those movements and voices that precede us—those ancestors’ shoulders upon which we stand. I am honored that you have concretized the ideal of GLOBAL I Aam in your book. The “virtual saints and souls” found in Dispatches from the Vanguard: The Global International African Arts Movement versus Donald J. Trump are our call to living our imagined lives and are the lights that lead our way.

__________________________________

Patrick A. Howell’s book, Dispatches From the Vanguard, is available from Repeater Books.