On the Hidden Pain of V.C. Andrews, the Woman Behind The Flowers in the Attic

There has been widespread confusion over the medical battle that began for Virginia at the age of 15. (Although, amazingly, even to this day, some fans I’ve encountered and who comment on Facebook pages are surprised to discover Virginia was disabled.)

Many believe that what happened to her in high school eventually brought about her early passing at the age of 63. That would be true if you could develop the argument that her arthritic condition weakened her immune system to the extent that cancer could fatally invade her body, but this would be unscientific conjecture.

The most incorrect information is that Virginia fell down a stairway in high school and suffered a trauma to her back. There was no fall down the stairs—and certainly nothing like the stairway fall in My Sweet Audrina. Yet Virginia’s disability has been described that way in countless articles, in introductions to book reviews, and even by radio and television reporters. Part of the reason for the mischaracterization of her physical issues might very well lie with Virginia herself and somewhat with her mother.

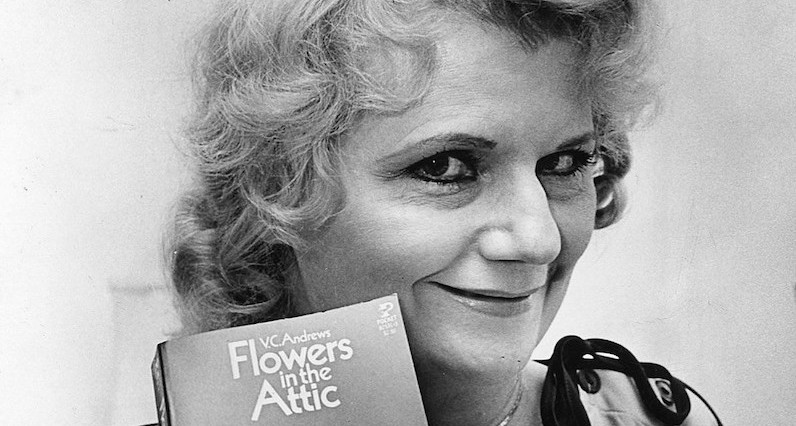

Even before the 1980 People magazine article and its photographs that Virginia ranted about, she was tight-lipped when questioned about her medical condition. In letters to and phone conversations with her family, she railed against the reporters and commentators who wanted to create “some sort of paralyzed creature struggling to type out her fantasies.” She saw herself being depicted as “The Humpback of the church of bestsellers, a creature dressed in beautiful clothes to distract the viewer from seeing the abnormalities.”

She railed against the reporters and commentators who wanted to create “some sort of paralyzed creature struggling to type out her fantasies.”Although Virginia and her mother did attempt to—and often succeeded in—putting on a pretty and happy facade, as her fame began to develop rapidly, there were more and more calls for public appearances and an accompanying desire to publicly explore her physical disabilities. Virginia resisted them all. How easily and quickly someone else seeking more attention might have seized on the opportunity to use their hardships to stress the accomplishment of doing something outstanding.

But not Virginia Andrews; she was not after a promotional gimmick to sell herself and her work.

She lived by the credo that if you didn’t talk about the issue publicly, at least for the hour or so of the necessary book promotion, it was as if it didn’t exist. Her disability remained a real mystery for some time, and it is misunderstood even now. Rumors love a mystery. Virginia said that mean-spirited people, even neighbors, fanned the flames of the idea that she had been beaten, severely punished. It really wasn’t until years after all the medical treatments that Virginia, once in the public eye, began to address her physical condition. Often, she deliberately exaggerated to confuse reporters. Despite her malady, she had what some might call a “sick” sense of humor about it. Others might say she was trolling those who had no right to inquire about such things.

Virginia’s niece Suzanne recalls how much her aunt enjoyed toying with the press: “She’d even giggle about it. It annoyed Virginia that reporters concentrated on her physical disability so much that she would confuse them about it. It was her kind of sweet revenge. To do it, she would exaggerate or even invent some treatments.”

She lived by the credo that if you didn’t talk about the issue publicly, at least for the hour or so of the necessary book promotion, it was as if it didn’t exist.The fact is that no one in her family had ever heard of some of the things she said in Rubin’s 1981 Washington Post article “Blooms of Darkness” describing what had happened to her—especially stories about surgeons having strokes while operating on her or predictions of many more surgeries, including a dangerous, life-threatening one supposedly on the horizon.

In that article, however, Virginia related a diagnosis that the family recognizes as closest to their understanding of the issue: “When it finally became obvious that the bone spur had thrown my spine out of alignment, it led me into a bout with arthritis, which I needn’t have had if they had taken the bone spur off immediately.

“This went on for four years, starting when I was about 18. Then they began to correct the damage with operations. I had four major ones and have one more coming up.”

However, then she veers into territory nobody can confirm and which most doubt: “I can have corrective surgery, but I’m a little leery of doctors because they made mistakes with me. One doctor had a small stroke while he was operating. The saw slipped and he cut off the socket of my right hip.

“I have to have a new replacement. But the operation is very serious for me, life-threatening. I’m not in pain now . . .”

How much of this was a dramatization and/or exaggeration, no one in the family can say. But most of her family knew the truth about the origins of her physical disability.

Her sister-in-law Mary remembers being told that Virginia had taken a wrong step on the stairway at Woodrow Wilson High School, which resulted in badly twisting her hip. “My husband, Gene, had found out that the doctor who had examined her after she complained of persistent pain believed the twist had been violent enough to tear a membrane on his sister’s hip. Eventually, after more physicians examined her, the conclusion was she had started to develop little bone spurs.

“The family was deeply concerned. Although I didn’t know her when she was very young, I knew from the way everyone spoke of her that she was thought of quite highly. She had been achieving well in school and was quite a beautiful young lady.

“But I must say that when I had first met her and times after, I didn’t hear her moaning and complaining. If anything, I was moved by her avoidance of self-pity. It was and is easy for me to understand why she didn’t want to dwell on it, especially later on in the newspapers and magazines when she became quite famous.”

Her cousin Pat, who not only had Virginia and her mother live with her but often as a very young girl had spent time at their home, blames the confusion about the details of Virginia’s accident on Virginia’s mother telling people her daughter was “pushed down the stairs in high school, permanently disabling her. It was those jealous girls.”

Many were willing to accept this description.

Pat conjectures that Virginia’s medical condition embarrassed her mother and that was the real motivation behind her lies. She believes that at times, Lillian hid the fact that Virginia had any medical issues at all. Both she and her husband, William, were proud of Virginia’s beauty and depressed about her inability to resume a normal life. Lillian’s attempt to hide or ignore Virginia’s disability is understandable, considering Lillian’s beliefs and personality, and this might even go far to explain Virginia’s own attitude about herself and how she was portrayed.

Virginia began 12th grade, but in October of that year, the pain had continued to the point where she was unable to walk without difficulty to and from school. Both Virginia and her parents were quite aware of the struggle. According to Pat, “One event stands out regarding school and her illness. Virginia came home from school upset that the crossing guard had lost her temper with Virginia for walking across the street so slowly. She said, ‘Hurry up, Gimpy’ or ‘Hurry up, Limpy.’”

Surviving relatives recall Lillian’s anger at the way her daughter was being teased and treated by her peers as well as adults like the crossing guard. Virginia continued to endure excruciating pain, making sitting at a school desk for long periods of time difficult. It was clear that all the normal treatments for a twist or a pull on muscles and tendons weren’t working.

School records show that Virginia had to leave Woodrow Wilson High School in Portsmouth in October 1940, in her senior year. The records note “Health reasons.”

But what was the true medical history that followed?

Virginia claimed that although she was suffering from the pain caused by bone spurs that formed on her spine, she was unable to convince physicians during those early days that she had a problem. As she described the issue in a number of interviews and in her conversations with family, doctors told her that she walked too gracefully to actually be in so much pain. “I found out that looking too good is a terrible way to go into a doctor’s office. They don’t take you seriously.”

We recognize in her experience a timeless problem for women. As recently as May 3, 2018, Camille Noe Pagán, in an article in the New York Times, related that “research on disparities between how women and men are treated in medical settings is growing—and is concerning for any woman seeking care. Research shows that both doctors and nurses prescribe less pain medication to women than men after surgery, even though women report more frequent and severe pain levels.”

Cousin Pat’s father, Fred Parker, recommended that the family take Virginia to Johns Hopkins for the evaluation of her problem. It resulted in her first surgery to correct the bone spurs. If anything, this surgery seemed to have made the problem worse. Virginia was then brought to another hospital, the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville, where she underwent a second operation. As far as anyone could tell, the original diagnosis was still the most likely to be true: the twist on the stairway exacerbated an arthritic condition that was resulting in a fusion of her bone structure. The second operation was an attempt to clear that up but would require Virginia to be in a body cast afterward.

Despite all this, there was a silver lining in store for Virginia. Although it wouldn’t show itself until nearly 40 years later, there was something that wouldn’t have happened if Virginia hadn’t been brought to the University of Virginia for another attempt at alleviating her condition, something that would trigger her fame and fortune years later.

According to Pat, Virginia told her that while she was at the University of Virginia hospital, she became infatuated with a handsome young doctor, who was equally infatuated with her: “They became very close while Virginia was a patient there. She told him about her endeavors and dreams of becoming a published author. Consequently, he thought he would give her a story to write, a true story. He confided in her about his strange young life. The premise, and surely the shocking revelation for Virginia, was that he and his sisters had been hidden away in one of Charlottesville’s huge mansions for over six years to preserve the family’s wealth. I never learned his name or the family’s name. The information was, however, straight from Virginia to me.”

We don’t have to guess what this anecdote became, but interesting questions arise: Did the doctor specifically mention an attic? How many children were incarcerated in the true story? Were there any twins? Who imprisoned them? Was their grandmother involved? We know, of course, that there are four children in Flowers in the Attic. Pat believes her own family members, absent the incest element, were possible models for the kids. She has a brother who became a doctor and two younger siblings who are twins.

What are the similarities that we do know of? The setting of the story the doctor told and the setting of Flowers in the Attic are both in the Charlottesville area of Virginia. The older brother wanted to become a doctor. The hiding of children to regain an inheritance matches Corrine’s motivations in Flowers in the Attic. She hid her children because if her father knew she had children, she would be cut out of his will. One potentially similar plot point in the doctor’s story is that if the trapped children no longer existed, the path to the next beneficiaries would be activated. Of course, Virginia had much more to add to this plot premise by way of the incestuous relationship between Corrine and Christopher Sr., who we eventually learn is her half brother.

However, it’s fascinating to contemplate that Flowers in the Attic stemmed in part from Virginia’s painfully long ordeal. Readers who conjectured that the novel was really Virginia’s own story in some way now have witness testimony to its actual origins. What remains remarkable is the length of time between Virginia’s hearing the premise of the story and her actually writing the novel. She later claimed in a newspaper interview to have written it “one night, while I was in bed. It was a 22-page handwritten draft.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Woman Beyond the Attic: The VC Andrews Story by Andrew Neiderman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Gallery Books. Copyright © 2022.