Six Memoirs That Go Beyond Memories

Every memoir author eventually confronts the same question: Who cares?

Sometimes you hear that taunt in your head late at night as you try and fail to sleep. Maybe it’s the voice of an old acquaintance whose respect you once craved. Or worse, perhaps this voice sounds like your own, the most insecure and anxious version of you. The truth is, it’s never not a little embarrassing when someone hears that you’re writing a book and asks you what it’s about.

“Uhh … me … it’s about me … my life … it’s a memoir.”

If and when you venture down this particular writing path, you’ll quickly discover that memoirs are not diaries. The best don’t work solely from the author’s biased, Hollywood-style recollections, where every character is either “good” or “bad.” Lives, and memories, are more complicated than that.

Memories aren’t merely scenes; they’re microscopic moments: powder sticking to your fingers after scarfing a funnel cake; holding your right arm out of the passenger window to feel it bounce in the wind; the hilarious whine of middle-school voices singing along with Kurt Cobain or Eddie Vedder.

Some of the strongest memoirs don’t just describe how something happened; they reveal something larger about the world the author and the reader share—even if they don’t know they share it. Frequently, the writer’s biggest revelations uncover, or unlock, something the audience didn’t know was inside of them.

What does it take to try to bring those past events to life on a page? As I learned while writing my memoir, Life on Delay, it requires interrogating what we thought we knew, both through research and talking with other people—the nonfiction subgenre known as “reported memoirs.” These six books are some of the finest of the form.

The Night of the Gun, by David Carr

Carr, the late New York Times media columnist, published the definitive reported memoir in 2008 when he set out to investigate his life—going straight at his history with substance abuse. Crucially, he probes the validity of his own memory: He uses his training as a journalist to interview individuals from all corners of his past. As you would imagine, these conversations are revelatory. Take the titular example: Carr recounts a particularly grim night when he showed up high at the house of his friend Donald, who was menacingly holding a gun. When he and Donald speak about this event decades later, Donald remembers it quite differently: “I never owned a gun … I think you might have had it.” Carr goes deep on the complexities of marriage and fatherhood, and offers a portrait of the ever-changing newspaper industry. The work is profoundly honest—he doesn’t exactly portray himself as a hero. This book influenced my own memoir in many ways. For starters, it gave me the inspiration to interview my kindergarten teacher, my sixth-grade girlfriend, and, later, my family.

[Read: Whatever you write, there you are]

All You Can Ever Know, by Nicole Chung

Chung, an Atlantic contributing writer, tells her story of transracial adoption and reconnection with her biological family in her excellent debut memoir. Although Chung’s story is unique, her writing about belonging, parenting, and connection is widely relatable. Her prose is understated, unflinching, and flat-out fierce (in the best way). She poignantly describes how her early childhood peers—all white—viewed her, the only Korean girl in class, with confusion. Like many adoptees, she yearns for the real story of how she ended up as a member of a different family. Instead of a straightforward answer, she finds a set of competing narratives, but excavating her history reshapes—and ultimately strengthens—her own family bonds. I just started reading a galley of her next book, A Living Remedy, out this April: It’s about navigating loss, grief, family, and distance during the coronavirus pandemic. I can’t wait for it to reach the wider world.

After Visiting Friends, by Michael Hainey

Certain questions haunt us for decades. For Hainey, a magazine journalist with stints at Esquire, GQ, and Spy, who’s now the deputy editor of Air Mail, that haunting involved a family ghost. He spent years wondering: How did his father die? After Visiting Friends is his intimate, noirish pursuit of the answer that his extended family and others close to his parents refused to give. The book’s subtitle is simple and artful: A Son’s Story. Hainey’s goal with this project is not merely to get to know the dad he lost when he was 6 years old but to find meaning and fulfillment in the search itself. Like Carr, he walks us through midwestern newsrooms and barrooms with crystalline detail and precise imagery. Although many will read it as a father-and-son book, in a major way, it’s really about Hainey and his mom. As he seeks an answer to his big question, he ends up posing another: What happens when you ask what you’re not supposed to ask?

[Read: She never meant to write a memoir]

Stay True, by Hua Hsu

You probably saw this book on virtually every 2022 best-of list, and rightfully so. Stay True packs so much heart and texture into its 208 pages that you may not even realize the depth of what you consume if you breeze through it. (It’s an impressively fast read.) Hsu has produced easily one of the best nonfiction books about friendship ever, right up there with Patti Smith’s Just Kids. Rather than telling his whole life story, Hsu zeroes in on his college years, specifically his life-changing relationship with Ken, a friend who was murdered before the two graduated. He turns to his enviable music library as a portal to these years. We don’t just picture Hsu goofing off in front of a video camera; we practically hear Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s canonical mid-’90s banger “Tha Crossroads” in the background. As a music obsessive, I was hooked on Stay True right from the epigraph page, which offers a couplet from Pavement’s 1994 slacker-rock anthem “Gold Soundz”: “Because you’re empty, and I’m empty / And you can never quarantine the past.” The back half of that lyric is Hsu’s thesis statement, as is the book’s cover (designed by The Atlantic’s Oliver Munday), which is a photo of Ken pointing a camera back at the photographer: Even when telling part of a friend or loved one’s story, we’re still setting out to tell our own.

The Art of Memoir, by Mary Karr

Karr’s name has been synonymous with “memoir” ever since her mega-bestseller The Liars’ Club helped solidify the so-called memoir boom three decades ago. I became a lifelong Karr fan back in college after reading her follow-up, Cherry, in a freshman-year creative-writing seminar. When I took a brief leave from The Atlantic to start writing my own memoir, my wife surprised me with a paperback of The Art of Memoir, Karr’s how-to guide; aptly, it is a quasi-memoir. Far from a textbook or self-help book, The Art of Memoir is a meditation on reading, craft, and revision. Karr teaches in the MFA program at Syracuse University and brings a professor’s warmth to the text. She doles out indispensable advice, such as how to let a single moment tell the story of a whole year of your life. More than anything, she shows you how to go to that place you’re probably too afraid to go when you sit down to write. I would recommend this book to any writer—fiction or nonfiction—at any stage of their career.

[Read: David Foster Wallace, Mary Karr, and the dangerous romance of male genius]

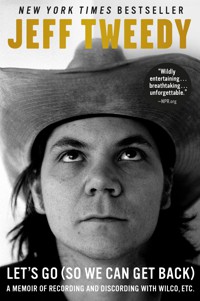

Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back), by Jeff Tweedy

It’s not fair when someone so good at one thing turns out to be so good at another thing. Tweedy, the Wilco frontman, released one of my favorite music memoirs of all time in 2018. Let’s Go credibly challenges Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Keith Richards’s Life, and Anthony Kiedis’s Scar Tissue, even if Tweedy is decidedly less famous than all three. He takes us through his formative years and deep inside the rise and fall of Uncle Tupelo, his old trio that more or less invented “alt-country.” In Carr–esque fashion, he also periodically passes the mic to his wife and others, offering interstitials and rebuttals to certain events. I’ve never read a book that elicited such a huge range of emotions in me as a reader. At times, it’s laugh-out-loud funny, such as when he recounts how, as a young boy, he tried to convince his childhood friends that he wrote a Bruce Springsteen song. Other times, it’s achingly sad, namely when he describes his journey through drug addiction and rehab and, more recently, the death of his father. This Atlantic story about some of Tweedy’s favorite song lyrics will give you an idea of how closely he pays attention to both rhythm and pithiness as a writer. His next book, World Within a Song, coming this fall, appears to set out to show how the music we love doesn’t merely provide a soundtrack to our existence; it actually shapes our life.