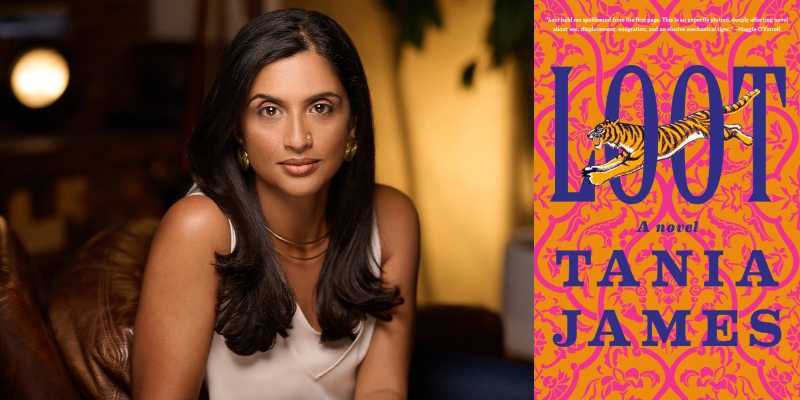

Tania James on Trust, Truth, and the Desire to Create Something That Lasts

This week on The Maris Review, Tania James joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Loot, out now from Knopf.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: One of the reasons that Tipu Sultan wants this elephant clock to be made, he says, is to provoke among the masses a sense of awe and its close cousin obedience. And that is such a powerful description of what stuff can do.

Tania James: Yeah, I don’t think he actually commissioned the elephant clock. I kind of created this moment. But I think he would’ve really responded to that object that was created and designed by a 12th-century Muslim polymath. His name was Al-Jazari and he is well known in the Arab world. I don’t know. But when I discovered this thing, this was a whole other world of automatons that I had not read about.

I had only associated automatons with Europe, but here he was doing it in the 1100s. And I think that Tipu Sultan would’ve been really attracted to this idea behind the elephant clock, which is that each part of it represents a certain part of civilization, but none of those civilizations he’s mentioning are European. So I felt that he would really have been attracted to that, but I didn’t find that anywhere in the historical record. I just made up that he had that commission.

MK: You create this tension in this first part of the book and second, in that we don’t know who to trust. He doesn’t know who to trust. Are the French allies? Will they be betrayed? Tell me about the political climate as we begin the novel.

TJ: Well, in the beginning of the novel, Tipu Sultan is constantly asking for help from France to aid him and give him money and give him soldiers to fend off the British. He knows that there’s a bit of stasis between the third and fourth war, but he is prepared to confront the British one more time.

So he has a lot of French expats at his court. He has a lot of French engineers, he was really trying to build up a navy. Nobody had ever done that in India at the time. So by 1799, once Tipu is defeated, Abbas himself attempts to leave India and I think he doesn’t anticipate how complicated leaving will be. And so he joins an East India Company ship as a carpenter, but he actually winds up on a French pirate ship, and is sort of conscripted or pressed into labor on the ship.

I think one of the things he comes to feel strongly by the end of this journey by the time he gets to England is that it’s every man for himself. There’s no such thing as this is my national identity and I’m from here and I’m loyal to this country, this nation. He really comes to not care about any of that, whereas at the beginning of the novel, he cares pretty deeply about being loyal to Tipu Sultan.

MK: Absolutely. One of the things that you do in this novel is you give Abbas such wonderful relationships. So at the start, he is kind of mentored by Monsieur Du Leze. It’s a friendship that evolves over 30 or 40 pages or so, but you really feel it. Tell me about them.

TJ: I felt like all of the characters whose consciousnesses I was interested in, they’re all ostracized in some way. Or they’re secretly, they somehow feel outside of the world that they’re a part of. He is a clockmaker and a maker of automatons. He arrives at Tipu’s court because Tipu wants clockmakers to come from France.

So Louis XVI sends him, but soon after he gets to India, there’s the French Revolution and subsequently a law, an actual law that was passed that banned royalist French people or aristocrats from coming back to France. And so he’s sort of exiled and sort of stranded in Mysore for a long time and he doesn’t quite fit in with the other expats because he’s somewhat closer to Tipu Sultan.

And so he doesn’t stay where the other expats and soldiers stay. He kind of has his own apartment and I think he just has this sort of artistic lonerness about him and he sees something in Abbas. He doesn’t know for sure if Abbas is that talented. He kind of takes a chance on him. But then I think Abbas comes to save his life in a way. And they become kind of mutually indebted to one another.

I have not seen this relationship so much in fiction, the mentor [and mentee]. I feel like I see it in film and maybe it’s a kind of archetypal relationship in film, or maybe it’s just simply what I’ve been drawn to lately. But I was interested in that relationship between mentor and mentee.

Some of it is not entirely pure all the time. I think Abbas at one point is thinking of Du Leze almost in a greedy kind of sense. Like, I want what you have. I had a friend who, when he was 15, he saw somebody doing capoeira in the street and he just was so mesmerized by it. He became that person’s student, and he basically said to him, I want what you have.

And he now is a capoeira teacher himself. But I just took that one line. That’s really what it boils down to a lot of the times, as a younger person or as a novice, you look at that person who seems to have mastered and has such confidence and you want it so badly. That felt like one of those personal ways into character for me.

MK: Absolutely. And even the metaphor of making a clock or repairing a clock seems like it’s the kind of thing where you have to be, so, what’s the word I’m looking for?

TJ: I follow that metaphor. They do have to kind of be very still and rigorous.

MK: It seems like there’s this great tension, between what is this stuff? This is just stuff! And Abbas’s wish to create something that will last. And people don’t last.

TJ: Yeah. I can’t imagine having that kind of ambition to make a thing that will outlast me. Maybe that’s because we’re a product of our time. Everything seems more ephemeral now than it ever has, but I think he is maybe a product of his times.

One of the first things that he encounters in the novel that makes him feel that way is a verse from a poet, which was an actual verse from an actual poet. It just works some kind of magic on him and he wants to replicate that feeling in someone else, that kind of feeling of wonder. I think as the novel goes on, he becomes irrationally attached to this object that he made.

By the end of the novel, I think he has to come back to that sense of wonder, which has not so much to do with the thing that was made, but more the feeling of boundlessness that you’re on the verge of something. That that is where the spirit of artistry lies.

*

Recommended Reading:

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century by Kim Fu • Our Country Friends by Gary Shteyngart • Breakup by Anjan Sundaram

__________________________________

Tania James is the author of the novels The Tusk That Did the Damage and Atlas of Unknowns and the short story collection Aerogrammes. She lives in Washington, D.C. Her latest novel is called Loot.