Television Is Better Without Video Games

“Fudge,” I remember saying, only I didn’t say fudge, I said fuck, a word for adults. I was playing The Last of Us, a narrative video game for adults about a zombie apocalypse, and I had just died for what seemed like the thousandth time in the first room with a “clicker,” the game lore’s name for a medium-difficulty enemy. These “infected”—it’s classier not to call them zombies, and this is a classy zombie-combat game, one with a story—had become misshapen thanks to a cordyceps brain infection, which devoured mankind almost overnight. The clicker was ghastlier than others, because it had lived long enough for the infection to fully engulf its formerly human face, fungal fibers enrobing it, teeth jutting out like barbs. An older infected is a more resilient one. In a video game, that translates to a more difficult baddie to beat. It would be too boring to tell you all the things I had tried, but none of them had yet worked. Fuck this fucking game.

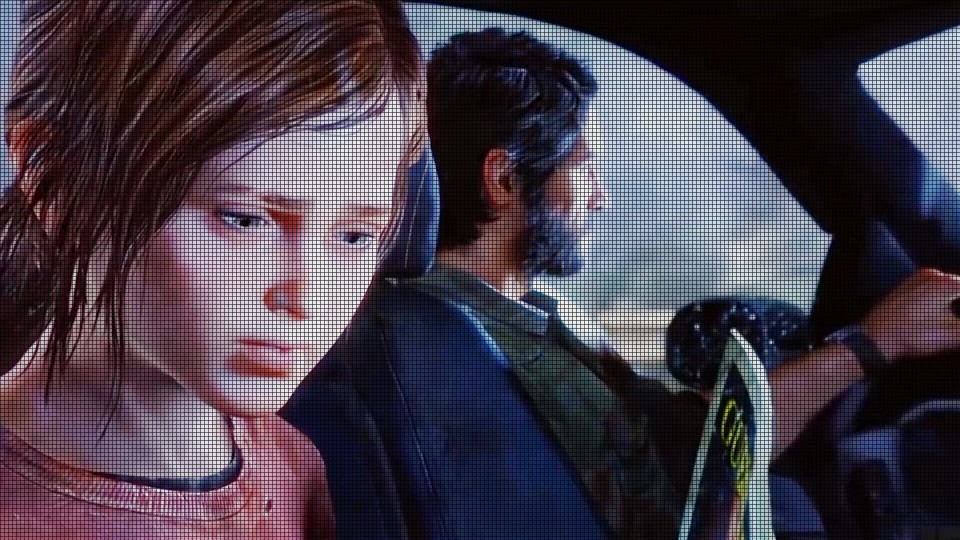

As frustrated as I felt, I was also confused. I couldn’t shake the sense that the combat was getting in the way of the story, acting as filler, just there to give me something to do in between metered doses of narrative. By now, a lot had already happened in the game’s plot. A younger version of my character, Joel, had tried to escape the infection on outbreak day, but his daughter, Sarah, had not survived. This loss, mated with the literal end of the world, broke Joel’s spirit. Two decades later, in an authoritarian quarantine zone outside Boston, the hardened Joel forages and trades for supplies with a companion, Tess, who will soon sacrifice herself too—another blow to Joel’s spirit. Our goal, our mission—these are necessities in a game—is to escort a young girl named Ellie, who appears to be immune to the infection, to a hospital across the country, where doctors working for a resistance movement known as the Fireflies hope to extract a cure.

[Read: Video games are better without characters]

It’s a lot to hang around the neck of a sneak-and-shoot PlayStation title. Kind of makes you wonder: Why would anyone bother? I’ve long reasoned that no serious storyteller would select video games as their medium of choice, given how much better literature, cinema, and television are at narrative expression. Just make a television show!

They finally did. Neil Druckmann, who co-created the The Last of Us game, and Craig Mazin, who wrote the Chernobyl miniseries, are the showrunners for HBO’s adaptation. But as I watched the show, a new problem arose: Sitting on my couch, unburdened by the need to sneak behind infected, throw bottles as diversions, or carry out the other mechanical demands of combat gameplay, I felt differently bored. The adaptation revealed that there just isn’t that much to the story.

Despite Pedro Pascal’s adept performance, Joel seems one-note, a man less deadened by the loss of his daughter than just deadened. And Bella Ramsey’s Ellie makes scenes that felt thoughtful and mature in the game seem amateurish on-screen. Some were reproduced shot for shot, line for line, including a formerly funny role-play Ellie improvises in a submerged hotel lobby and the saccharin end of the second episode, in which Ellie celebrates the view across a decades-overgrown, overlit Boston vista: “You can’t beat the view.”

These vaguely tender, human moments worked in a video game. But in the television adaptation, they just seem forced and sentimental. Because I didn’t have to pilot Joel and strangle infected, my eyes took in scenes more fully and my brain asked new questions about them. The world-building became unconvincing. All of the roads and highways are littered with the corpses of abandoned vehicles, long since overtaken by vegetation. But somehow supply trucks can get through? The fascist state actors are supposedly ruthless, Gilead-style, but the quarantine zone seems run-down more than threatening. The Fireflies seem to operate out in the open without issue. Narrative plausibility isn’t much of a problem in games, because you’re so focused on pressing buttons.

Trudging through HBO’s The Last of Us, I found myself wondering how I ever could have thought that this would make good television. If only I had something to do while watching these flat characters traverse burned-out cities—like, say, shooting zombies.

The problem with video-game storytelling is a structural one. Games demand action, and action, for better or worse, entails movement through space and collision with other objects in that space. You move something (a starship, a Pac-Man, a grizzled veteran of the zombie apocalypse) and hit or avoid something else (asteroids, Blinky, cordyceps-afflicted clickers). As game technology has evolved, it has honed and refined these capacities to a glossy luster. Games look incredible—realistic and visually persuasive. You can move around a huge expanse in the worlds they simulate. Often you can’t do much within them, because every storefront, vehicle, bench, and other object would have to be programmed to interact with a character that might enter, drive, or sit atop it. Best to save that effort for grappling on precipices or firing rifles at fungal-infected former humans. That’s where the craft of game design takes place, too: in player action (for example, confronting the enemy AI that made the clicker level so difficult for me).

But the expectation of movement and collision also limits the capacity of games, especially games that want to tell stories. In the game’s prologue, the player, controlling Joel’s daughter, wanders around a whole house, getting their bearings, exploring rooms, reading a note on the fridge, opening drawers, and learning the game’s verbs. It’s a preposterous waste of time narratively, and one that the TV show not only doesn’t need but cannot support. Instead, Sarah wakes up in a gently lit suburban bedroom, and set dressing, cinematography, framing, and editing show us her situation quickly and efficiently. Setting and character development happen rapidly, allowing the viewer to focus on dialogue and relationships rather than where the door is and how to open it. TV makes use of the trappings of life to shine a light on life itself. It does that by capturing the world through the lens. But games do not share this capacity. Everything must be constructed from whole cloth. In The Last of Us Part II, the video-game sequel, the development team went to enormous lengths to make rope physics convincing—you know, throwing a cord or cable. If you want to throw a rope on TV, you give someone a rope and point a camera at them.

[Read: Video games are better without stories]

In games, exterior action is easier than inner life. Movement and collision detection, doors and drawers, ropes and firearms. What a character thinks or feels still must be communicated by language, and that requires either dialogue or artifacts—like the found note on the fridge—or both. Listening, watching, and reading require the player to become a viewer, and changing modes has consequences: It’s harder to process narrative information while ramming buttons to craft Molotov cocktails. But it’s easy to scroll Instagram while watching HBO’s The Last of Us, because you can scan images while scanning other images.

To address this problem, games often lean on traversal as an overarching structure. You move through the simulated world, overcoming obstacles to reach an interim goal, at which point a passive interlude delivers a chunk of story. Traversal becomes fractal: Get to the other side of the quarantine zone to get to the tunnel in order to get to the outskirts of town. Along the way, the player must hang out with the characters through every footfall, searching cabinets, climbing ladders—boring details that television spares the viewer. As you keep moving, the environment can change, and those changes can give the player the impression of novelty: Hiding from zombies in a factory at night is different from chasing them down in a field under broad daylight.

This framework does not lend itself naturally to the development of deep, emotional human characters. People don’t tend to reveal their true selves while careening across a landscape. Unless, of course, civilization has ended—a cheap setup that, I must begrudgingly admit, motivates character development in an exigent way. The most famous literary and filmic specimen that focuses, as games do, on spatial traversal amid existential threat is Lord of the Rings—which, of course, exerted a strong influence on the development of games in the first place. The novel and film Children of Men also feature a cross-the-country-to-the-clinic plot, but its premise—civilization has collapsed from decades of human infertility—is far more intellectual than The Last of Us’s zombie apocalypse, making the work a head trip more than a road trip. As in Contagion and Station Eleven, infirmity arrives in The Last of Us suddenly and all at once, ending the world like an atomic blast rather than a death marathon. And then, dystopian apocalypse—not to mention pandemic dystopian apocalypse, sheesh—feels tired, played out. Saving the world after its tidy end is no longer a gritty or courageous theme. It’s a lazy and implausible one.

All the worse, then, that the first two episodes of The Last of Us series follow the plot, action, settings, and even dialogue and camerawork of the game faithfully. Along the way, we get some televisual nods to the game world the show has invaded: the high-dynamic-range lighting for one, although that’s common enough in cinema these days, thanks to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. In his first encounter with a clicker, Joel must silently reload a gun, a challenge the game’s player is spared.

But the third episode takes a turn from the original material, even as it covers similar narrative ground. In the game, after Tess sacrifices herself so that Joel and Ellie can escape an infected horde, the two make their way to Bill’s town, an armored enclave run by a paranoid survivalist with whom Joel has previously traded goods and favors. Just as Joel is a one-note haggard man whose personality amounts to his simple, if tragic, past, so too is Bill a flat character, neurotic, mean, and ugly. The game’s dialogue devolves into Ellie hurling fat jokes at Bill, and the two exchanging lines that include the word “fuck,” because that’s how you know this is a serious game for adults. Hunting for a car battery that would allow the pair to drive west, Bill discovers the hanged corpse of Frank, his former “partner,” a term left somewhat ambiguous in the game’s main action. The two had had a falling out some time ago, and Bill decided to go it alone, like a real survivalist. Among the narrative props, the player can read a suicide note Frank wrote after getting infected. In it he writes to Bill, “I want you to know I hated your guts.” And Bill responds, to Joel and Ellie and the player, “Well, fuck you too, Frank. Fuckin’ idiot.”

The television show holds on to Bill and Frank and the town, but completely transforms their backstory and their fates. In the process, the show reveals the limits not only of video games, but also of television adaptations of games.

[Read: Video games are better without gameplay]

It’s a sweet, tender episode, brilliantly written by Mazin and adeptly acted by Nick Offerman (Bill) and Murray Bartlett (Frank). Bill is the same survivalist, but complexified. He’s into wine, which he knows how to pair with protein. After years of solo subsistence in his toughened encampment, Bill ensnares Frank, a passerby, in one of his perimeter traps. Frank sweet-talks his captor into letting him go, and then eat, and then shower—deeds Bill agrees to because he is clearly lonely, not because he is a fool. Mazin disambiguates the game’s use of partner, giving Bill and Frank a tender sex scene, followed by two decades of real partnership, shot in vignettes that show both alliance and conflict—over isolationism, over decoration, over strawberries. Frank develops a degenerative disease, but Bill cares for him dutifully. Eventually, Frank decides he has had a good enough life and orchestrates an assisted suicide by overdose—which Bill decides to administer to himself, as well. The two succumb, together, silent, content. Only after all this backstory transpires do Joel and Ellie show up, looting the house and the town for supplies, which is what one does in a video game.

It’s as if HBO commissioned Mazin, the television writer, to execute a takedown of the game-writer Druckmann’s shallow understanding of the human experience and its retelling in words and deeds. In the game, Bill is a cartoon, a tougher guy there to make tough-guy Joel seem somewhat more complex. In the show, he’s a man constantly struggling to reconcile his drive toward isolation with his need for companionship. In the game, Bill’s town is a simple warehouse for supplies; in the show, it’s a community, if broken, which people tend to and in which they come together. The gay love story was untellable in a game. Even 2020’s The Last of Us Part II, which depicts Ellie’s lesbian relationship, earned as much ire as praise from gamers, as that community continues to wage a private culture war over the very idea of any supposedly “political” theme in games. Meanwhile, Ellie’s discovery of a gay-porn magazine among Bill’s possessions, in both game and show, revert homosexuality to mere sex acts, rather than relationships—which game-Bill repudiates too.

Most of all, it would be impossible to tell Mazin’s version of Bill and Frank’s story in a game, because that story plays out in their heads and in their hearts, on the foundation of a thousand tiny deeds of ordinary life easily written and filmed—Bill’s culinary adeptness; Frank’s tested tolerance for firearms; tears shed over a berry not tasted in two decades—but impossible to make active in gameplay. Prior efforts to do so, including the French game designer David Cage’s reliance on timed button presses (known as quick-time events) to carry out verbs beyond “Move” and “Shoot” amount to terrible jokes. With so many better stories to tell, and so many better ways to tell them, why would a storyteller slum it with games instead? It’s just not interesting to watch an angry man escort an irritable girl across the country amid a cartoonish zombie apocalypse cosplaying a credible global pandemic.

This leaves games, and HBO’s attempt to adapt one of the medium’s supposedly finest ones, in a difficult place indeed. In one outcome, a game such as The Last of Us becomes a staging ground for building an audience and testing an idea, which real storytellers then mine and transform into proper stories. In another, games subsist as a narrative subclass, where a story can be good but only with the codicil for a game. And in yet another, the adaptation becomes a game of its own, a challenge to overcome the inexorable flaws of the source medium and then to be judged in relation to that disadvantage. In each case, games transmit their fungus into the brains of creator and viewer alike, doomed not to die but worse: to live on, forever perhaps, under the blight of video games’ infection.