The French Food Co-Op That Fought Nazis With Energy Bars

“In Europe in the 1940s, there were only two ways out: Marseille or Auschwitz,” writes David Rousset, a French author and Holocaust survivor, in the preface to La Filière Marseillaise: Un Chemin Vers la Liberté Sous l’Occupation. Unoccupied Marseille offered safe harbor from Nazi persecution and a potential escape to the United States. So, as Paris fell under German bombs in 1940, the Mediterranean port was bombarded with exiles from across Europe. The influx of artists, intellectuals, Jews, and activists made lodging, work, and food scarce. A group of refugees found all three in the most improbable of places: a clandestine co-op that produced fruit and nut bars.

Nowadays, food bars provide energy or replace meals. But those made by the Cooperative des Croque-Fruits were more than mere nourishment: They were a means of survival. Nutritionally, they fortified the meager food rations. Financially, the bars filled the workers’ wallets with enough francs to live comfortably. Politically, delivery workers carried resistance messages with the bars in a clever act of epicurean espionage. Socially, perhaps the most important ingredient for uprooted exiles, the cooperative created much-needed community and bonhomie. Like Snow White’s seven dwarfs, the members would sing as they worked, “L’alimentation qui réjouit, la friandise qui nourrit!” (“The food that delights us, the confection that nourishes us.”)

Rebellious Marseille was an apt setting for this courageous co-op. As part of the Free Zone, France’s second-largest city had a starring role in the resistance to the Nazis. Using a run-down château as a safe house, American journalist Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee miraculously secured exit visas for around 1,500 artists and intellectuals who were on the Nazis’ most-wanted list. While awaiting their papers, this cultural cognoscenti would gather at the Brûleur de Loups café. Perhaps it was the pastis, perhaps it was the revolutionary spirit of their Surrealist comrades, that galvanized three of them to cook up the idea for the Cooperative des Croque-Fruits at the Vieux-Port haunt.

Artist Guy d’Hauterive had the initial idea. The Catholic film critic Jean Rougeul was named the official head of the co-op because the Law of October 3, 1940 banned Jews from many jobs. Since the co-op structure was illegal at the time, they registered the business under the alias Fruits Mordoré (“Bronze Fruits”).

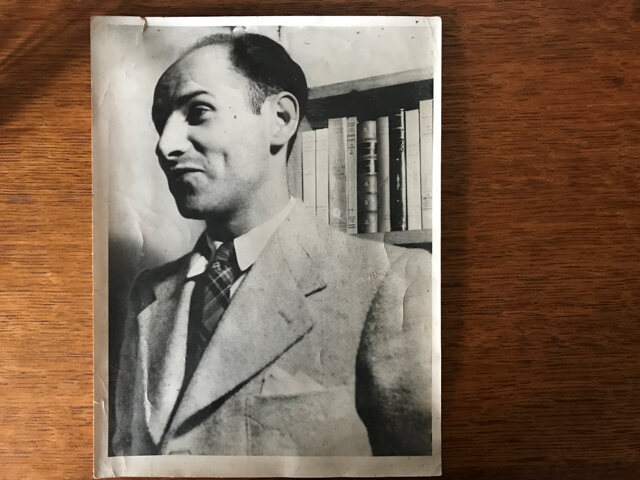

But it is the third co-founder, Sylvain Itkine, who is the leading character in this little-known story. His charisma and compassion might have played a part. Alan Paire, a writer who has covered the Croque-Fruit story, remembers a compatriot saying, “I’ve never met anyone who was disappointed in Sylvain.”

How does a writer-actor-director who dropped out of school at 14 end up running a food business? A role in Jean Renoir’s film about a publishing co-op, The Crime of Monsieur Lange, gave Itkine a taste for these equitable enterprises that were gaining traction in the 1930s. The actor also trained in political resistance as a card-carrying Trotskyist who performed in agitprop theater groups. The Cooperative des Croque-Fruits was a story of life imitating art.

Itkine sold his precious typewriter and borrowed money from relatives to buy machines for grinding nuts and dried fruit as well as to rent a space near the Gare St.-Charles train station for the co-op. He enlisted his chemist brother, Lucien, to craft a recipe for the bars out of foodstuffs traded in the busy port. North African dates and almonds were the primary ingredients. Depending on what the ships stocked that week, dried apricots, orange zest, and sweet potato purée could also be mixed in. Irène Itkine, Lucien’s daughter, says that the recipe “might have been inspired by Algerian Jews,” influenced by Marseille’s large Maghrebi population.

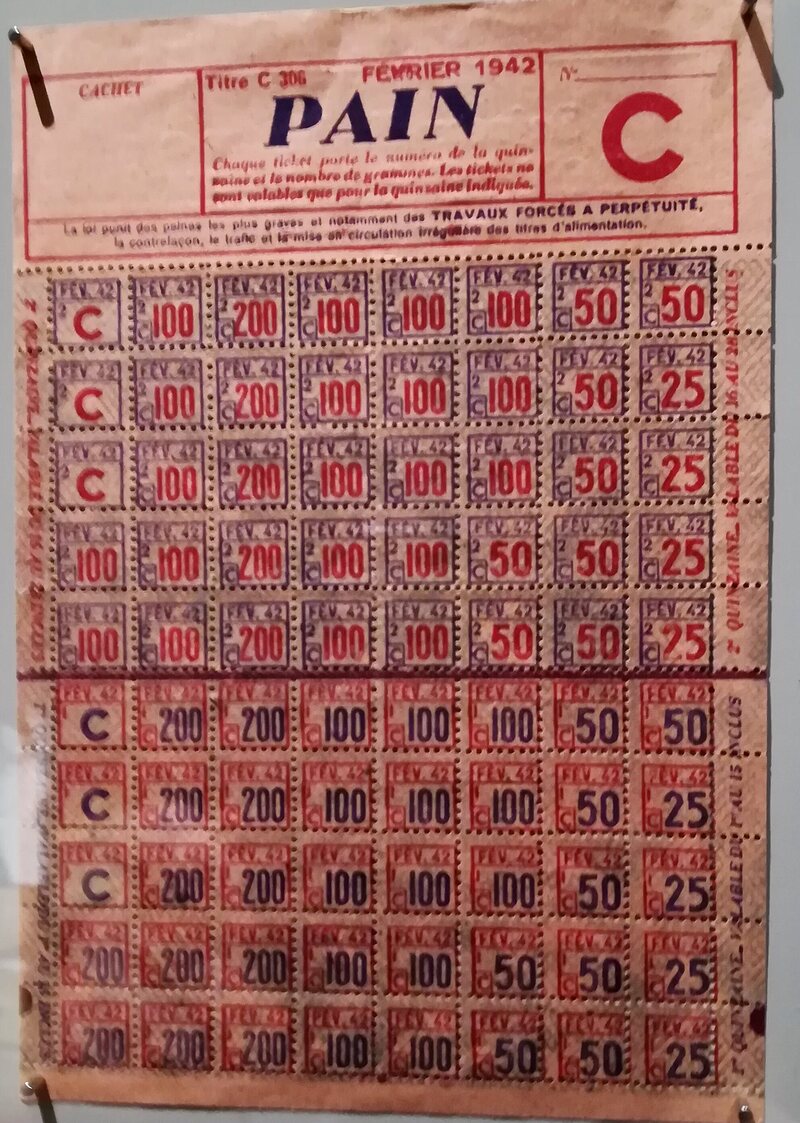

According to Paire, some found the bars delicious while others found them disgusting. In a time of widespread food shortages, calories and shelf-life trumped taste. Plus, the bars weren’t limited by the tickets d’alimentation (food rationing cards). One worker would measure out the bâtonnets magiques (magical sticks) into 30-gram pieces. A rouleur would roll the fruit paste into 1-centimeter x 10-centimeter logs; an enrobeur would coat them in crushed almonds; and a plieur would neatly wrap them in shiny bronze (mordoré) paper to catch the customers’ eyes like a Twix bar.

The work was easy enough to be performed by the crew of young culinary amateurs, artists, intellectuals, activists, and Jewish professionals (such as doctors and lawyers). It took just three hours to make around 3,500 bars. Theater director Jean Mercure was notoriously slow, while the famous musician Francis Lemarque was the fastest, his fingers in shape from playing guitar (which he did during shifts). “Against this backdrop of threat and anguish, we experienced an unforgettable sequence of friendship and solidarity,” croque-fruitiers André and Ginette Thierry told Paire in an interview for an article in the French weekly L’Obs in 2016.

Regardless of their role, every co-op member was equally paid for the fruits of their labor (except for the three founders, who were paid double). Compared to the 40-franc/8 hours wages of the average Marseille laborer, the 200 or so members brought in 70–80 francs for a 4-hour shift. This rate paid for a decent hotel and left ample time for artistic endeavors (unoccupied Marseille was an underground capital of culture before the Nazis arrived). “Their goal was to work less to make more,” says Catherine Itkine-Henon, Sylvain Itkine’s daughter, “the opposite of the CAC40 [France’s S&P 500.]” Profits weren’t the priority—a good quality of life, and survival itself, were the bottom line.

The fruits mordoré were sold at local tobacconists, boulangeries, and markets. Itkine’s leading-man charm made him an ideal salesman, but selling was only part of his role. At each stop, the activist-actor promoted the resistance efforts via leaflets and verbal messages. With clients across the city, Itkine could spread the word far and wide, and since he was free to roam with his job, it provided the perfect alibi. He also was a natural at it, having been part of the revolutionary Fourth International organization with other co-op comrades. The co-op’s hiring was even an act of resistance, as they employed illegal refugees while they awaited exit visas from Varian Fry.

While other resistance fighters were publishing underground newspapers or enacting guerilla warfare, the Cooperative de Croque-Fruits found their own way to support Marseille’s role as the capital of La Résistance. Before the movement really gained momentum in 1943 when smaller groups joined forces against Nazi Germany, the fruit bars helped plant the rebellious seeds. Artists Jacques Hérold and Jean Effel designed eye-catching ads to promote the bronze bites. In one, a buzzing bee brings a naked Eve a package of Croque-Fruits. The slogan reads, “Croque-Fruit: Not the forbidden fruit.”

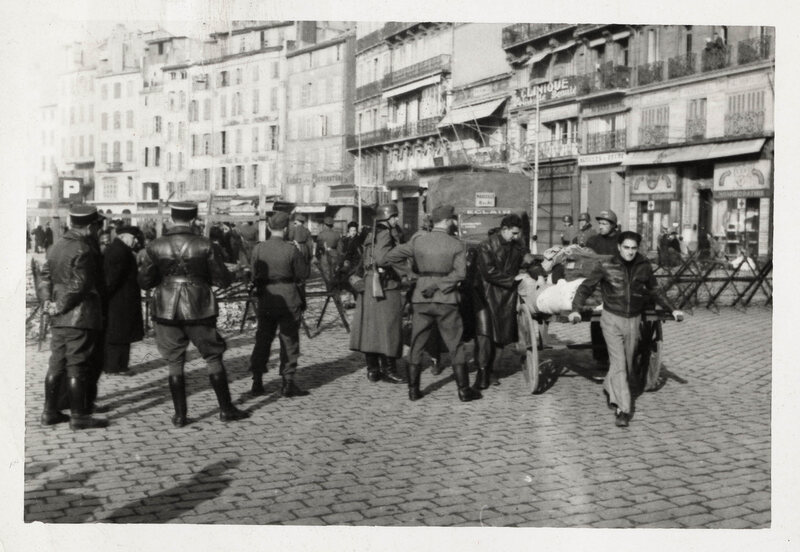

But in 1942, it became one.

In November of that year, Marseille finally fell to the Nazis, and the supply of dates and almonds dried up. In January 1943, as thousands of Jews were deported during the city’s infamous rafles (roundups), the Germans sent a letter to fire all juifs at the co-op. When they shut down the company a month later, Sylvain and Lucien Itkine, and some of their compatriots fled to Lyon to join the resistance there via the MUR (Mouvements Unis de Résistance) intelligence network. The Itkine brothers never returned to Marseille.

Using the code name “Maxime” in the MUR, Sylvain Itkine was responsible for identifying German agents and Lucien gathered information on how they were trained. Just one month before Liberation, Lucien was arrested during a roundup of Jews. He was sent to Auschwitz, ultimately dying at the Mauthausen concentration camp. After being betrayed by a spy who’d infiltrated his network, Sylvain was handed over to the Gestapo and never seen again. No one knows for sure what happened to him: Some accounts say he was tortured and killed by Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon,” after refusing to talk, while others say he was shot with fellow resistance fighters.

Just as Varian Fry’s pivotal role in World War II was celebrated only after his death (and now on Netflix’s new series Transatlantic), the Cooperative de Croque-Fruits remains an unsung tale in Marseille and beyond. The co-op’s building was demolished after the war, and even its road, the Rue des Treize Escaliers itself, disappeared during the city’s reconstruction. There’s little documentation, save for a few sound bites by former croque-fruitiers and their descendants. And within these testaments, memories vary, including the bar’s recipe itself (grated carrots and ground hazelnuts were also alleged ingredients).

Yet, what is certain is that this motley crew of exiles and artists combatted Nazi forces; that they cleverly used food as a form of activism and survival; and that their unique co-op saved lives while making daily life bearable, even enjoyable. In the words of Irène Itkine: “It was a real utopia.”