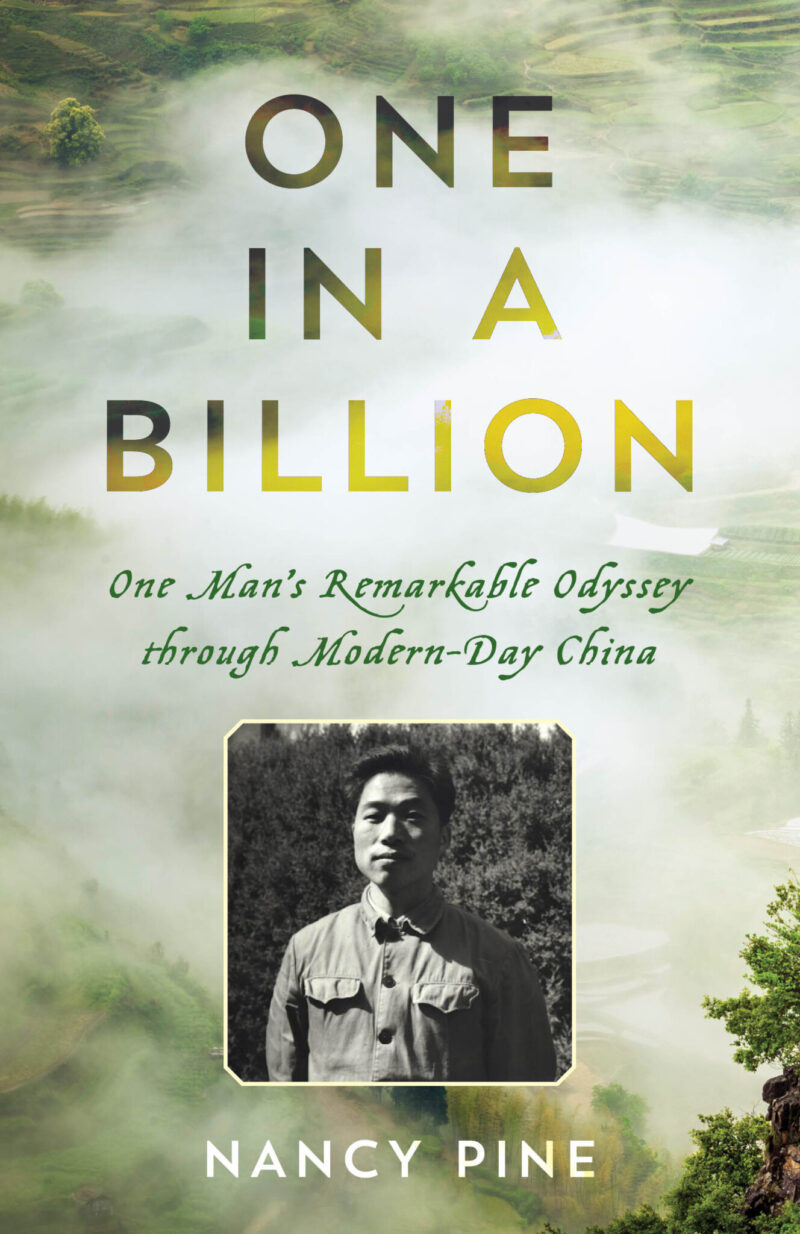

An Wei: From Chinese Peasant to Powerful Role Model

In this second post about An Wei, an unlikely role model who never gave up his values and his determination despite massive difficulties, I’d like to share more of this unique man’s story.

In this second post about An Wei, an unlikely role model who never gave up his values and his determination despite massive difficulties, I’d like to share more of this unique man’s story.

He grew up in a poor village in the middle of China, worked hard to improve his abilities, became an interpreter for world leaders, and began a democratic congress in his village. Modern China provided him education, but also hard-hitting challenges that he confronted one after the other.

A week before he graduated from college where he studied English, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution to promote continuous class struggle. An Wei’s dreams vanished. No longer could he go to England to perfect English; no longer could he get a job. The Chinese leader demanded they remain at college and uncover “bad elements” in the administration and party. A hideous year followed, but An Wei learned how to hold onto his values and sidestep odious assignments.

Two years later he was sent to a reeducation school to work with his hands, live in poverty, and restudy Mao Zedong’s writing on Communist ideology. Despite continuous setbacks throughout the Cultural Revolution, An Wei was learning to push back and survive.

The following is excerpted from my biographical portrait of An Wei called One in a Billion.

On December 1969, An Wei waited to climb onto the trucks that would haul him and dozens of fellow government workers north. Posters on nearby walls showed enthusiastic workers striding off to the fields with banners flying and radiant expressions. An Wei and his fellow “recruits” could find nothing worth smiling about. They were prisoners of the reeducation movement and the Cultural Revolution.

As the line of trucks lumbered up the steep road to the plateau, the men settled in for the long, cold 300-kilometer trip. An Wei pulled on a winter hat and wrapped his scarf tightly around his neck to protect himself from the stinging chill.

Being sent to a farm to learn from peasants seemed like a cruel joke. According to Chairman Mao, the skills and knowledge An Wei had acquired in school were worthless. Only farmers had wisdom and knowledge. An Wei’s world felt upside down.

As the trucks rumbled on, he vowed to hang onto English. He had labored hundreds of hours to learn it in high school and college. Although he had burned his journals out of fear they would be used against him, he would preserve what was inside him and those English translations of Mao Zedong’s writings in his bundle would help.

In the pitch-black, the trucks ground to a halt near a cluster of single-story buildings. Stiff and cold, the men climbed down. An Wei looked beyond the dimly lit buildings to the silhouettes of hills. They were a long way from city life.

The housing, with its wooden sleeping platforms, reminded An Wei of high school, only worse. Each of them had just enough room to lie down, but not enough to turn over. From that first night, An Wei loathed it.

The jobs burned his muscles and sapped his energy. He ran long distances to haul firewood from far away hills and planted crops using ancient tools that required him to stay bent over for hours. He knew he was stubborn enough and had the farming experience to survive, but to what end?

When they were not working, the cadres had to read Chairman Mao’s works and criticize themselves. In an attempt to add substance to the required readings and writings, An Wei began dipping into the English translations he had brought and learning from their footnotes that explained Chinese historical events to English-language readers. Because Mao Zedong was highly literate and had embedded many literary and historical references in his writings, the footnotes added richness. In fact, the English volumes sometimes helped An Wei understand the original Chinese better.

However, what he was doing was against school regulations, and soon his platoon leader, Commander Fan, a worker-peasant with little schooling, called him in.

“You are here to touch your soul and receive reeducation,” the commander lectured. “How dare you read a foreign language? It’s against all rules.” He ordered An Wei to turn in his English volumes.

An Wei tensed with fury, but he willed himself to keep his tone respectful. He was not about to give up.

“Commander Fan, if a good citizen must spread Mao Zedong Thought to the rest of the world, isn’t it imperative to read some of it in English? Otherwise, how can we convert foreigners?”

Knowing that he was taking a risk, An Wei pushed Mr. Fan well beyond his meager education. He quoted a phrase from Chairman Mao’s works that many Chinese people had difficulty understanding and asked him what it meant.

The commander paused, then responded with an incorrect answer that included severe punishment. An Wei, gloating inside but staying respectful, pointed out that the passage actually said that for someone to learn from his mistakes, he needed help to understand his errors. He continued. “I learned the correct interpretation because I read it in both English and Chinese.”

Commander Fan’s face showed frustration and humiliation. Without comment, he dismissed An Wei, letting him keep the English volumes.

From then on, An Wei continued to read the English works often, but only by climbing far into the hills behind the school. He had been lucky with Mr. Fan, but he did not want to challenge other reeducation school leaders or cadres who would not be so easily convinced.

Read What American Men Can Learn From One Chinese Peasant (part one)

Read a Review of One in a Billion HERE

Find out more about author Nancy Pine HERE

Image courtesy of author

The post An Wei: From Chinese Peasant to Powerful Role Model appeared first on The Good Men Project.