Elie Honig Analyzes Justice, Jersey-Style

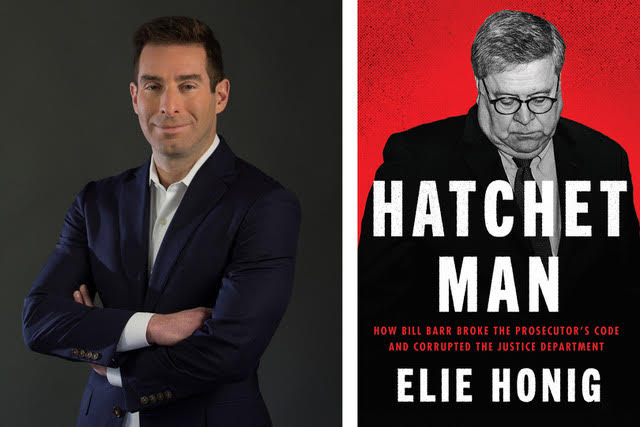

Elie Honig weighs in on democracy, politics, and his role at Rutgers’ Center for Secure Communities. Courtesy of John Shapiro

When Elie Honig drives along New Jersey’s highways, he often passes exits that remind him of investigations he led when he was assistant attorney general for six years at the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice.

“You learn as a prosecutor that crime is everywhere,” he says, recalling the murder case in which a man shot two victims in Jersey City, drove them down to the woods of Atlantic County, then buried the headless and handless torsos in one grave and the two heads and four hands in another. And the case where a manager at the Tick Tock Diner in Clifton tried to hire a hit man to murder his uncle. And the 42-kilogram, $1 million cocaine bust in a warehouse less than a mile from Honig’s house.

“It’s part of why it’s such an interesting job,” he says.

Honig, who grew up in Cherry Hill and lives in Metuchen with his wife and two children, left the criminal justice division in 2018 to become a legal analyst at CNN, where he now fields questions about everything from voting rights and immigration to racial justice. But during the Trump administration, particularly after the January 6 insurrection, he answered one question more than any other.

“Everyone wanted to know, ‘Will our democracy survive this?’” he says. “I would answer, ‘Yes, our institutions are being tested, but they are strong.’”

That said, Honig, who had previously served for more than eight years as a federal prosecutor in the famed Southern District of New York (SDNY) in Manhattan, believes there are many lessons to learn from the Trump years. He is particularly concerned about what he describes as the “lasting structural damage done to the Justice Department” by former attorney general Bill Barr.

When HarperCollins approached him about writing a book uncovering what he describes as Barr’s “unprecedented abuse of power,” he immediately accepted the challenge. Using vignettes from his own days as a federal prosecutor—including stories of some of his more than 100 prosecutions of New York City Mafia members and associates—Honig illustrates how, in his opinion, Barr violated norms and principles that damaged the Department of Justice’s credibility and independence. Hatchet Man: How Bill Barr Broke the Prosecutor’s Code and Corrupted the Justice Department is due out on July 6.

The unwritten rules, ethics and values of the prosecutor’s code, Honig explains in Hatchet Man, include impartiality, independence and humility. “You learn it in the dingy conference room where you scarf down lunch and shoot the breeze with other prosecutors; you learn it in the well of the courtroom during the heat of battle at trial; you learn it from supervisors and judges and defense lawyers who keep you in line when you step out,” he says in the book’s first chapter. “It sounds like a parody of a Springsteen lyric, but the truth is that I learned more from knocking around the hallways of the SDNY than I ever learned from any law book.”

Though Barr served as attorney general twice, he had never tried a case as a prosecutor, which means he had never experienced the successes, failures and setbacks of the courtroom—as Honig did while serving under U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara (who was fired by Donald Trump in 2017). “I was sort of raised at the SDNY and taught to think of the U.S. Department of Justice as a beacon that stands completely separate,” he says.

Barr, on the other hand, viewed the job as political and “felt free to politicize the department,” Honig says. This attitude was at the heart of dozens of scandals during Barr’s tenure, he adds, from the early spin on Robert Mueller’s findings on Russian election interference, to attempts to squash a whistleblower’s complaint about Trump’s Ukraine dealings, to efforts to undermine U.S. prosecutors in the cases of Trump allies Michael Flynn and Roger Stone and to further Trump’s voter-fraud narrative.

“Real prosecutors do not seek simply to do what’s expedient, self-serving, or self-aggrandizing,” Honig declares in Hatchet Man. “Real prosecutors take the job—with all its attendant rewards, challenges, and sacrifices—to do things right.”

At the conclusion of the book, Honig proposes nine reforms that he maintains would help the justice department restore its standing as a “unique bulwark of independence in government,” including explicitly rejecting Barr’s view of complete presidential prosecutorial power and adopting specific rules limiting communication between the DOJ and the White House.

“A ‘hatchet man’ is someone who is willing to do anything to achieve their bottom line,” says Honig. “I think Barr will go down in history as one of Trump’s top enablers.”

Meanwhile, Barr has reportedly signed a book deal to tell his version of history. “Good for Bill Barr,” says Honig. “I’m sure he’ll have his story to tell. I’m glad my book is coming out first so I can give people the truth first.”

***

Honig’s talent for explaining legal issues in layman’s terms, whether the scandals of the Trump years, Supreme Court decisions, or the Derek Chauvin trial, is essential during these complex times, says Dana Bash, who works with Honig as a news anchor and chief political correspondent at CNN. “He always hits a home run when breaking things down for the public,” she explains, adding that she has developed a friendship with Honig that began by bonding over all things New Jersey. (Bash spent her teen years in Montvale and attended Pascack Hills High School.)

“A couple of months ago, around the time Bruce Springsteen was pulled over for a suspected DUI—charges were later dropped—Elie saw a photo of me wearing a Springsteen-themed mask and wanted to know where I got it,” she recalls. “I sent him a couple, because we’re both fans.”

These days, Honig also serves as executive director of the Rutgers Institute for Secure Communities, an umbrella organization focused on issues of criminal justice, policing and intelligence gathering. The institute’s primary goal is to push the school into the forefront of criminal-justice and national-security issues by delving deeply into police reform and helping communities build relationships between law enforcement officials and community leaders.

The institute is also building an intelligence-studies program, funded predominantly by a federal grant. This year, Honig taught a course in which students learned to research, develop, draft and present the kinds of briefings used by intelligence professionals.

One of his students, Nethra Jayaprakash, a 20-year-old sophomore from Edison, describes Honig as a dynamic, caring professor. “He brings in amazing speakers that share different perspectives,” she explains, including Samantha Vinograd, national-security analyst at CNN, and General Mark Hertling, another CNN analyst. “He also has amazing stories, including about his time prosecuting members of organized crime,” she adds.

Working at Rutgers is a full-circle moment for Honig, who was inspired to apply to Harvard Law School as a Rutgers undergraduate when a professor with an infectious passion for the law and criminal justice sparked his interest. That led to an internship with the Middlesex County public defender’s office.

It also extends a longtime family connection to Rutgers—his father, uncle and brothers also attended the university. “My family is so grateful to Rutgers, because both of my father’s parents were Holocaust survivors who immigrated to New Jersey,” he says. “Rutgers was our state school and affordable, so my father was able to go to college and law school and raise our family in a comfortable, middle-class, suburban lifestyle.”

***

After nearly a decade steeped in New Jersey criminal justice, Honig says he has seen the state begin to address the inequities built into the system and how police officers do their jobs. With the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, “there’s a real opportunity now to initiate meaningful change,” he says.

New Jersey’s sweeping bail-reform effort, which Honig spearheaded at the Department of Criminal Justice and took effect in 2017, is a particular point of pride.

“We switched the whole system from a money-based system to a risk-based system, so you won’t see bail bonds anywhere in the state anymore,” he says, pointing to studies that found 12 percent of New Jersey’s incarcerated population were people awaiting trial who could not post $2,500 cash bail. “It resulted in huge numbers of low-risk, nonviolent offenders stuck behind bars, whereas wealthy, dangerous people could pay their way out,” he says. “With bail reform, our jail population is way down.”

Yet there was resistance to passing the bail-reform legislation, which required an amendment to the state constitution. “I had bail bondsmen threatening me, as well as prosecutors and cops who were very skeptical of it,” he says. “But we fundamentally changed the system.”

[RELATED: Strange Bedfellows: How Mixed-Politics Marriages Survive]

On the other hand, Honig regrets not being able to implement sentencing reform while at DCJ. “There are mandatory minimum sentences that are pretty outrageous, which need to be eliminated or at least lowered,” he says. “I wanted to change the way our courts handle criminal cases, but there were just too many systemic obstacles.”

Overall, however, Honig says the level of interest in criminal-justice and policing reform is “at an all-time high right now,” and that the state has evolved to become smarter and more sophisticated in its approach to crime and law enforcement.

“We’re in the middle of what I hope is a long-term process toward new policies,” he says. “It’s energizing and satisfying to see police approaching their jobs differently and prosecutors willing to try new things.” New Jersey should not shy away from going after dangerous or violent criminals, he emphasizes, “but I also think that our policing had gotten way out of whack and focused way too much on nonviolent offenders.”

Meanwhile, he says, other concerns, such as white supremacy and domestic extremism, are moving front and center in the Garden State. “You started to see warning signs during my time at the Division of Criminal Justice, around 2015, that these issues were on the rise in New Jersey,” Honig says. Then came the January 6 insurrection: “That was largely based on misinformation and the spread of lies that the election had been stolen,” he says. “You see groups like QAnon, Proud Boys and Oathkeepers emerging as bigger and bigger threats, which was something that both Donald Trump and Bill Barr stubbornly refused to acknowledge.”

***

Between his work with CNN and Rutgers, as well as his own podcast, Third Degree, Honig has kept a busy schedule during the pandemic. But he says he has also enjoyed plenty of quality time with his family during this year like no other.

“We’ve gone kayaking on the Raritan Canal, and spent a lot of time on the Middlesex Greenway,” he says. But Honig admits he’s looking forward to getting back to in-person events that are still not quite back to normal, including Rutgers football and basketball games. “I’ve been going since I was a kid,” he says. “I can’t wait to get back to doing things I took for granted.”

The post Elie Honig Analyzes Justice, Jersey-Style appeared first on New Jersey Monthly.